In Bangladesh, Ajit Roy graduated from college with a chemistry degree, hoping to become a doctor or civil servant. But a run of bad luck derailed those dreams, sending him to look for work overseas.

He wound up at a farming machinery factory in South Korea. Six days a week, over shifts as long as 12 hours, he stood in front of a rack of metal cylinders, degreasing their surfaces with paint thinner and buffing them with a handheld grinder.

It wasn’t long before he began to have trouble breathing, and after nine months on the job, he found himself unable to walk without gasping for air. A doctor diagnosed him with a deadly lung disease that testing later suggested was related to his job.

“I would go through the motions of breathing, but feel like I wasn’t getting any oxygen,” said Roy, 41.

For decades, South Korea resisted admitting large numbers of immigrants, but a deepening labor shortage spurred by the world’s worst population collapse has left it with little choice.

Roy and the other workers at his factory were recruited through a program known as the Employment Permit System, which has become the country’s most important stopgap against the crisis. The EPS, which included 370,000 workers at the end of last year, is on track to add 120,000 more by the end of this year — up from 56,000 in 2019.

As South Korea hits the world’s lowest birth rate, a rural elementary school struggles to stay open amid a nationwide drop-off in school-age children.

Cambodia, Nepal and Indonesia send the most migrants. The vast majority work in manufacturing, where the labor shortage is most severe. The sector is expected to need an additional 300,000 workers by 2030.

But as the migrant program ramps up recruitment, it has come under scrutiny for what critics say is failure to guarantee safe working conditions.

Government data show that foreigners made up roughly 9% of the manufacturing workforce in 2021 but accounted for 18% of its 184 accidental deaths.

The criticism has focused on the powers the program gives to employers, which make it difficult for migrants to seek other jobs or protest unsafe working conditions.

“It essentially allows local employers to hold migrant workers hostage,” said Choi Jung-kyu, a migrant rights lawyer at the forefront of the campaign to reform the program.

The government, however, has suggested that the program suffers from the opposite problem: giving migrants too much freedom.

The labor ministry said in a written statement to The Times that nearly a third of migrant workers transfer out of their original assignments within a year, undercutting the mission of the program.

As a result, labor officials recently announced a series of measures — including a rule limiting transfers to certain regions — that make it harder for migrant workers to leave rural areas, where labor shortages are most severe.

“The EPS issues work visas to migrants on the assumption that they will work in these sectors suffering shortages,” the ministry said. “The basic rule is for them to stay at these workplaces.”

As for the higher death rate, the labor ministry said in its statement that migrant workers are clustered in smaller manufacturing companies, which tend to be more dangerous, and that language barriers and a lack of experience also make them more prone to accidents.

“We are working on strengthening health and safety standards across the board,” the ministry said.

: :

South Korea was once an exporter of labor, sending miners and nurses to Germany starting in the 1960s. But by the 1990s, following a period of rapid economic growth, jobs that were dirty or dangerous found increasingly few takers in the domestic workforce.

And so the government began looking outside its borders to fill the openings.

Its first attempt was a program launched in 1994 with 20,000 migrant workers. They often arrived deep in debt to unscrupulous middlemen who had recruited them. And because the workers were classified as “industrial trainees,” they fell outside the scope of labor laws, and often worked long hours in dangerous conditions for half the wages that South Koreans received. Many deserted their assignments, leading to a growing undocumented population.

So in 2004, the liberal administration in power replaced the old program with the EPS.

Cutting out the middlemen, the government directly recruited workers through formal agreements with 16 developing Asian countries, assigning them to jobs under one-year contracts after a basic Korean language test and medical checkup.

The new program gave migrants equal protection under labor laws. But that early reformist spirit was soon eclipsed by conservative administrations that prioritized the needs of employers desperate for workers.

Seoul has fewer people living on the streets than Los Angeles. But tens of thousands live in illegal units so small there is barely enough space to lie down.

The most significant change was increasing the initial employment contract period from one year to three years. This helped employers retain workers for longer, but made it more difficult for migrants to transfer out of the workplaces to which their visas were tied.

With few exceptions, migrant workers can change jobs only if their employers release them from their contracts — something labor-strapped companies are reluctant to do.

Experts said that even for reasons of employer misconduct, such as unpaid wages or safety lapses, the threshold to qualify for a transfer is high and the fine print complicated.

“The early scope of the EPS was far more limited than it is today,” said Chung Byung-suk, who was a senior labor ministry official when the program was created. “But over time, it was expanded and corrupted into something very different.”

: :

1

2

3

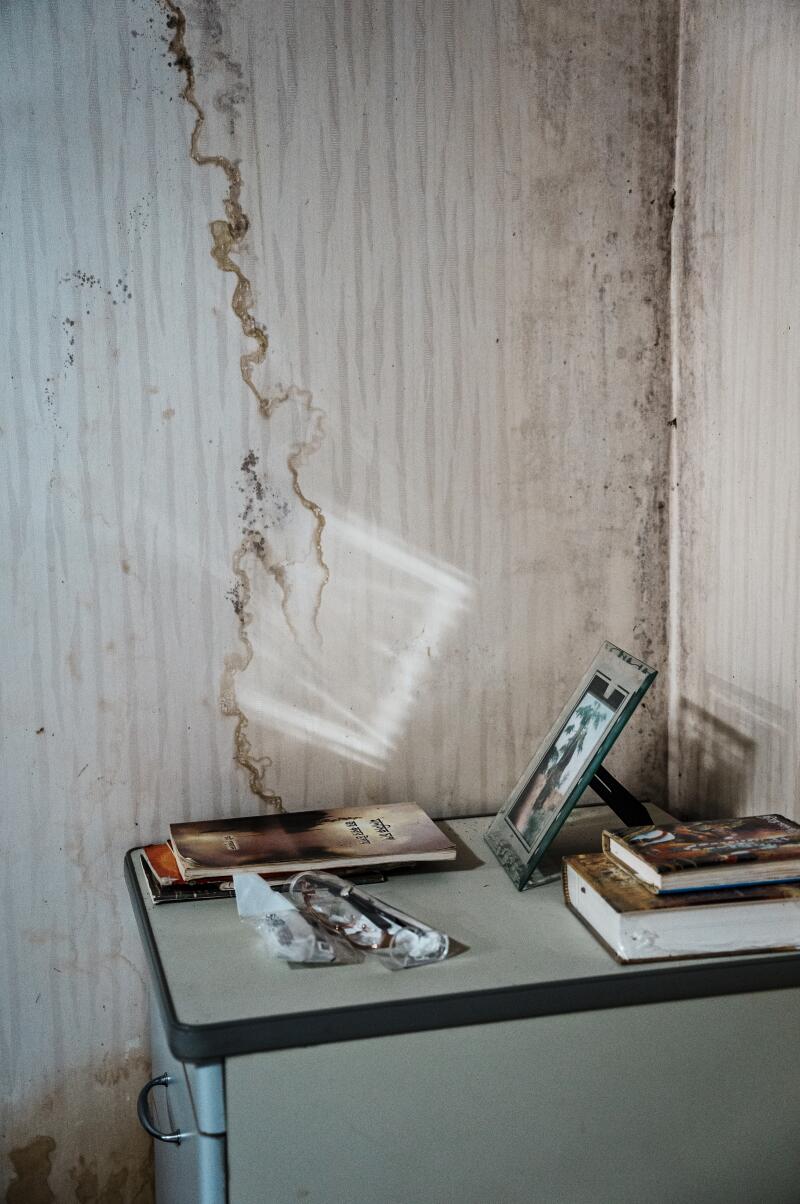

1. Mildew and water stain mark the wall where Ajit Roy lives. 2. Roy’s medication and supplements. 3. Roy holds up a picture of his parents on his cellphone.

Ansung Industrial, the company where Roy landed in early 2021, has won government accolades for its exports of equipment like backhoes and tractors. Located two hours south of Seoul in the city of Anseong, it has about 70 employees in South Korea, as well as a factory in China and a warehouse in Dallas.

The company gave Roy a clean bill of health when he started the job and moved into a makeshift dormitory on the second floor of the factory. He worked weekends and any available overtime to make around $2,500 a month, more than 10 times what he could earn for such work back home.

At his workstation, fumes from the paint thinner stung his nose, mixing in with the haze of metal dust emitted by the grinding.

“It always smelled,” he said. “You could feel the metal dust go down your throat.”

He said that he had asked a manager for a respirator early on, but was given a blue fabric mask instead. He wanted to find another job, but knew he was stuck at Ansung. An employer’s failure to provide proper protective equipment, while a violation of industrial safety law, is not accepted as a reason for a job transfer.

Roy said he was denied time off to see a doctor for his breathing problems, with a manager explaining, “We’re short-handed as it is.”

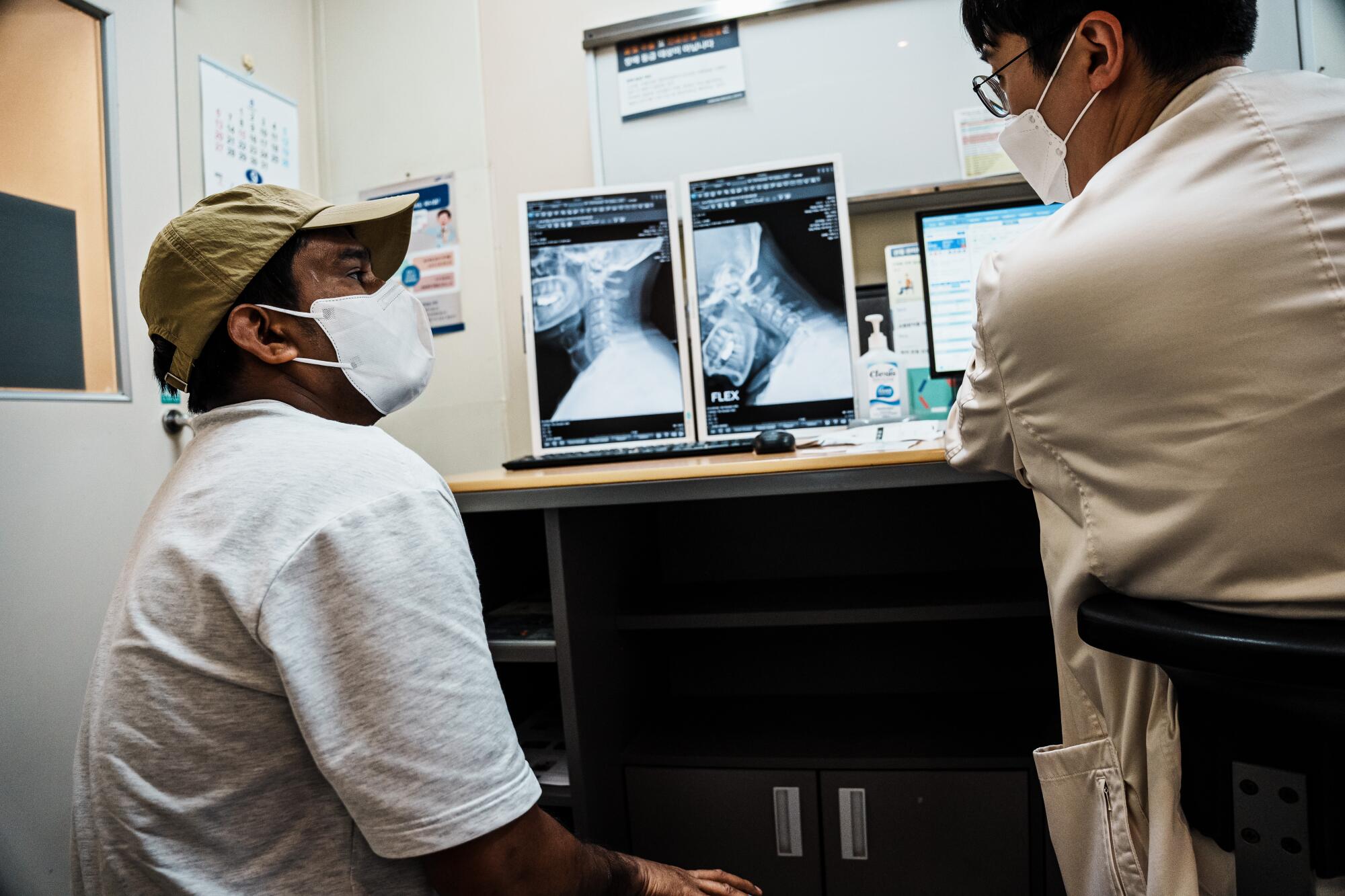

At a hospital in Seoul that December, Roy was diagnosed with interstitial lung disease, an incurable condition that has been linked to exposure to industrial pollutants. A CT scan showed heavy scarring in his lungs.

Foreign-born labor adds to demand for services and holds down costs of farm products, child care and other goods and services.

Unable to work and sinking into debt from medical bills, including $2,500 for biopsy, Roy took leave from the company to recuperate at a friend’s apartment.

In January 2022, with help from the Bangladeshi Embassy, Roy filed for workers’ compensation from the government-run Korean Workers’ Compensation and Welfare Service — an extremely rare step for a migrant to take.

Ansung sent a letter to the workers’ comp agency, known as KCOMWEL, saying all of its workers were supplied with industrial respirators and that Roy’s illness was caused by “a personal neglect of his own health.”

When reached for comment by The Times, a manager at Ansung declined to answer questions about Roy’s case.

“Our only stance is that we are hoping for a quick resolution from KCOMWEL,” the manager said.

: :

In December 2020, a young Cambodian farmworker named Sokkheng was found dead in the dormitory where she lived in Pocheon, just north of Seoul.

The case easily could have gone unnoticed. Most migrant workers who die without a clear cause are quickly cremated so their ashes can be sent home.

But a group of activists, including Choi and a Methodist pastor named Kim Dal-sung, who runs a local migrant workers rights group, tracked down the farm where she died after seeing Facebook posts from other Cambodian workers.

1

2

3

1. Inside makeshift housing on farms, where living conditions are often squalid and spartan. 2. The kitchen inside the makeshift housing on a farm. 3. Kim Dal-sung drives around looking for illegal housing on farms in Pocheon, South Korea.

Suspecting Sokkheng might have frozen to death, they pushed for an autopsy and postmortem occupational disease ruling. It showed that she had died from the sudden rupture of her blood vessels, a complication from untreated liver cirrhosis.

The government later ruled her death to be work-related because the heating in her dormitory — a flimsy dwelling made from sheets of synthetic insulator — had broken down, allowing the bitter cold to accelerate her illness.

Sokkheng’s death erupted into a national controversy, prompting a visit by a lawmaker to her dormitory and protests by migrant workers.

Arnulfo Solorio’s desperate mission to recruit farmworkers for the Napa Valley took him far from the pastoral vineyards to a raggedy parking lot in Stockton, in the heart of the Central Valley.

In response, the labor ministry began to grant job transfers to migrants who had been placed in uninhabitable housing. Sokkheng’s employer was fined around $220.

Pointing out that Sokkheng’s death was uncovered by sheer chance, Choi said he believes that a significant number of migrant workers are quietly dying from workplace illnesses, their cause of death simply marked as “unknown.”

Government data lend some support to that suspicion.

Of the 1,942 occupational deaths among South Koreans in 2021, 63% were linked to work-related diseases. But for the 138 deaths of foreign workers that year, the figure was 20%.

The government think tank Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs concluded last year that the disparity probably indicates that disease among migrant workers is being vastly underreported, due in part to bureaucratic hurdles and uncooperative employers.

Data collected by the Thai Embassy on the deaths of its nationals raise the strong possibility that large numbers could be related to workplace illnesses but are never investigated: 40% of the 533 deaths between 2017 and 2021 were attributed to “unknown causes.” That figure was 6.5% for the country’s overall working population.

“These workers are young and healthy when they arrive,” Choi said. “The fact that they are then suddenly dying from unknown causes after coming to Korea raises a lot of questions.”

: :

By the time the workers’ comp agency inspected Ansung Industrial last July, the factory had been completely renovated, with Roy’s old job outsourced to another company.

“Everything dangerous was gone — the chemicals, the dust,” said Roy, who accompanied the agency’s inspectors.

Luckily, Roy did have one important piece of evidence to help establish a link between his working environment at Ansung and his illness.

A year earlier, a fellow Bangladeshi worker put him in touch with Kim, the pastor, who arranged financial assistance for Roy and enlisted the help of a doctor specializing in occupational disease.

Dr. Kim Hyun-joo instructed Roy to collect a small sample from the industrial dust collector by his workstation. A laboratory test of the powder he brought back and the biopsy of his lung tissue showed that both contained silica dust, a carcinogen associated with scarring of the lungs.

If his claim is denied, Roy will probably be sent back to Bangladesh, an outcome he sees as a death sentence because the standard of medical care there is much lower.

As South Korea confronts a dark chapter of its history, a former soldier’s quest for repentance becomes a lesson in the fragility of memory.

“Even if I die, I would rather die here in Korea, where it will be in relative comfort,” he said. “In Bangladesh, death is a very painful process.”

The damage to his lungs is permanent. If his condition worsens, he will need a lung transplant. Part of this would be covered by a workers’ compensation package, but there will still be out-of-pocket costs.

That means, eventually, Roy will have to return to the manufacturing line. “There is nothing else I can do in Korea,” he said.

For now, nearly two years since he filed his claim, he just has to wait.

: :

The fate of migrant workers like Roy is more than just a humanitarian matter.

Other countries including Japan are suffering similar demographic cliffs, and South Korea will have to compete with them to attract migrant workers in the future.

“Nobody is going to want to come here if word gets out that workers are dying in this way,” said Kim Dal-sung. “This is not a problem of individual employers, but of government policy.”

The need for foreign workers will only grow.

With South Korean women now giving birth to an average of just 0.78 children — the lowest rate of any major country and far below the 2.1 children needed to maintain the current population — the number of working-age people is expected to fall from 36 million today to 24 million by 2050.

Despite the problems, the migrants keep coming.

Back in Cambodia, 29-year-old Va Chanda earned about $250 a month in a garment factory. After arriving in South Korea in January, she was making six times that picking lettuce.

But she said she was beaten with a watering hose for failing to understand instructions in Korean. She managed to escape after a friend helped her call the police and connected her to a migrant shelter, where she has applied for a job transfer.

Still, she said: “I still don’t regret coming here. I just need to find a better job.”

Japan is desperate for foreign workers — yet it’s cracking down on uninvited asylum seekers who are desperate for employment.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.