When Stephanie Gilreath set out to open a store in Imperial Beach, she figured she might face opposition and have to fill out a stack of extra paperwork.

After all, at Outdoor Woman she planned to sell camping equipment, boots, other adventure gear — and guns.

Most Americans live within 10 minutes of a gun store. The Los Angeles Times set out to determine whether easy availability is a key driver of gun violence — but it’s not that simple. This series explores the complex relationship between firearm access and gun crime.

She filed an application in May for a license to operate as a commercial retailer in the sunbaked San Diego County town just north of the Mexico border. The Imperial Beach City Council responded by instituting a 45-day moratorium on gun sales.

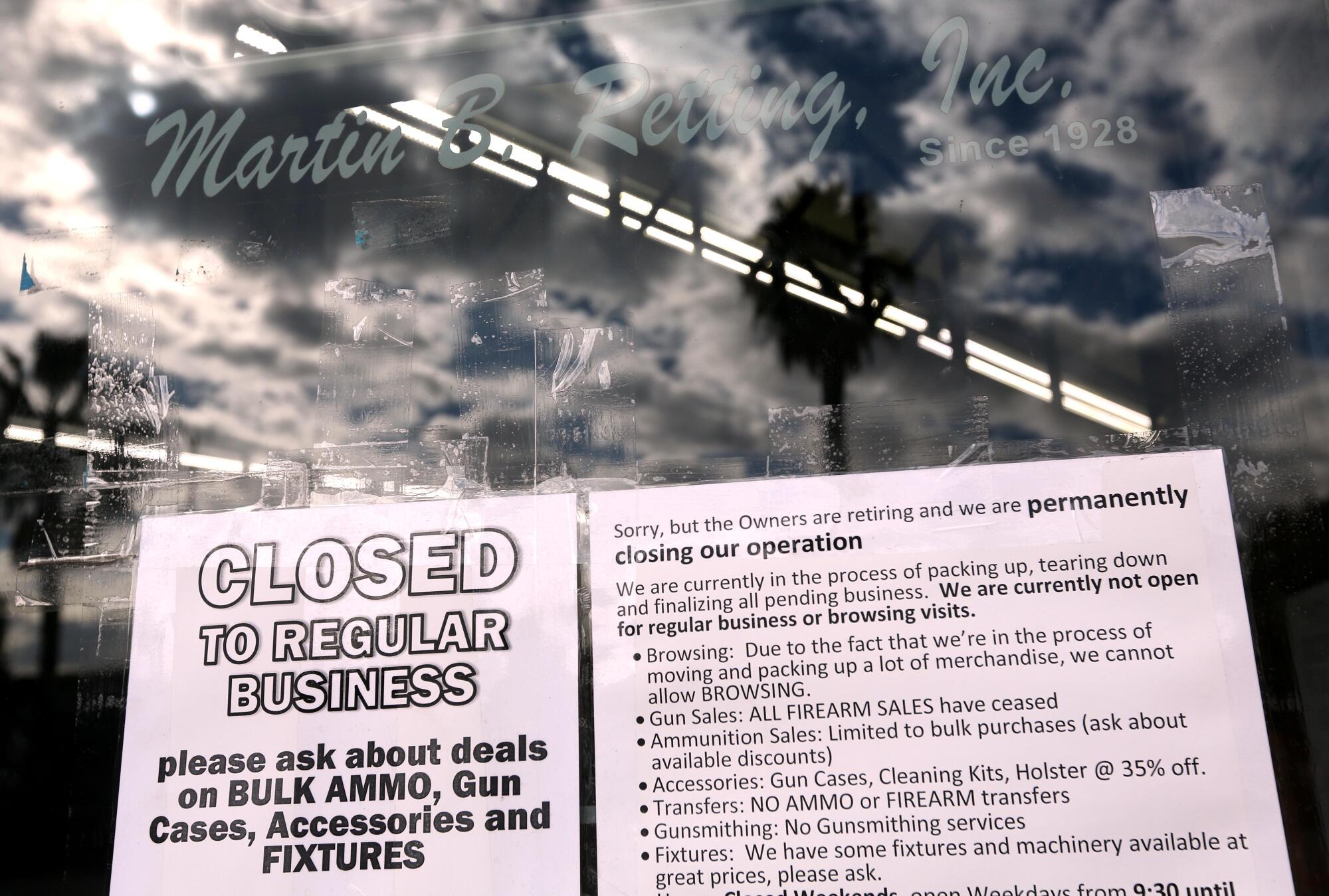

In Culver City, when a longtime gun store with a history of federal violations — and of selling firearms later used in crimes — announced it was closing, local gun control advocates faced an uphill battle to keep another dealer from replacing it.

They explored finding a wealthy benefactor to purchase the Martin B. Retting gun shop’s hulking white building or rezoning it to entice developers. In the end, the city purchased the property for $6.5 million. Retting has until the end of the year to move out.

In Southern California, it’s as difficult for a would-be retailer to open a gun store as it is for a city to keep one out.

Nationwide, there were nearly 79,000 firearms dealers as of January, a 20-year peak, according to an L.A. Times analysis. Some states saw 70% or 80% increases in the number of dealers between 2003 and 2023, while others saw a net loss of hundreds of gun stores.

California lost 518 dealers, a decrease of 17%, a greater drop-off than all but Alaska, Washington, D.C., and Illinois. The Golden State is still home to more than 2,500 licensed firearms dealers.

Several gun store owners interviewed by The Times said California’s strict firearms regulations and high taxes were significant factors in driving some fellow dealers to shut down their businesses or move elsewhere. But the issue of how and where firearms dealers should be allowed to operate in the state is largely defined at the local level.

The Times reviewed the municipal codes of 295 cities out of the nearly 500 cities in California. The analysis found that nearly two-thirds of the localities have instituted at least some restrictions on gun dealers. In 45% of the cities, a permit managed by local law enforcement is required. Nearly a third bar gun sales in residential areas, limiting them to certain commercial districts.

On Aug. 2, two days before Imperial Beach’s retail gun sales moratorium ended, the council approved legislation that would allow Outdoor Woman to open if it followed a host of new regulations. But for Gilreath, the bureaucratic hurdles and hiccups were not over.

“Back in the ’80s and early- to mid-’90s, California was a lot more gun-friendly,” she said. “That’s the way I really wish things were today.”

Gilreath got her first gun in 2012, after a scare with a trespasser one night at the house in Imperial Beach where she and her husband lived at the time.

The next day, they went to Big 5 Sporting Goods, and Gilreath picked out a shotgun. A couple of weeks later, her husband, who’s served in the Navy for 32 years, left town on his next deployment.

“So then I learned how to use it. While he was gone that whole time, I was going to the range every week,” Gilreath said. After he returned, “we’d walk into gun stores and, if I asked to see something, they handed it to him. … I did not want that to happen to another woman. And that’s why I started Outdoor Woman.”

While the gun sales moratorium was in place, Imperial Beach reviewed more than 100 California cities’ firearms dealer regulations. The council ultimately approved an ordinance that imposed requirements for video surveillance, storage and other aspects of the gun-selling business.

“At the end of the day, we want to make sure that we have a plan for any type of business that wants to operate in our community,” Imperial Beach Mayor Paloma Aguirre said in an interview the next day. “For a legitimate, reasonable and responsible store owner, it shouldn’t be torturous for them to go through the necessary steps.”

In September, more than six weeks later, Gilreath unlocked the future site of her business. Late-morning sunlight shone through big windows onto its dusty wood floors and stark white walls. The empty shop would need a major overhaul before it would be ready for customers.

“We have a wall coming down this week, flooring being replaced, extra lighting. I have to get bars for all the windows,” she said. “We’ve got displays that we’re putting in, then inventory and furniture.”

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That afternoon, she drove to Imperial Beach’s civic center to request an updated city license. Just days earlier, Gilreath had received a letter from the California Department of Justice rejecting her application to be a state-licensed firearms dealer.

The letter, which she had been waiting on for more than three months, said her application had been rejected because the city license didn’t contain the words “valid for the” before the phrase “retail sales of firearms.”

“I just thought that was hilarious,” Gilreath said. “They’re getting picky. They’re doing what they can to hold things up and not let it through.”

She also applied for a municipal permit for retail gun and ammunition sales in Imperial Beach, per the ordinance the City Council had approved the previous month.

Those administrative issues largely remained unresolved by the time of Outdoor Woman’s grand opening on Nov. 4. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives “lost our paperwork,” Gilreath said, which set back the license application process. And the city required her to pay another $200 to get a different permit.

The newly renovated space also still needed to be inspected by an ATF investigator before Outdoor Woman could start selling firearms, and that couldn’t happen until all the licenses and permits were taken care of. In the meantime, Gilreath continued to miss out on business.

“Everyone keeps coming in and asking for guns and ammo, and we have to say, ‘No, not yet,’” she said on Nov. 15. “It’s just one thing after another. … Welcome to Southern California.”

On Dec. 1, Gilreath learned that the last of the paperwork had cleared. Her store could start selling guns.

It was prom night in September at the Town & Country Resort on San Diego’s busy Hotel Circle. A succession of bearded men in cowboy hats, suits and boots streamed into a cavernous convention hall alongside women with fresh blowouts teetering on tall heels.

They were all gussied up for Gun Prom, an annual fundraiser that draws hundreds of firearm enthusiasts from across Southern California to talk, auction and celebrate guns.

Tickets to the event, which began with a silent auction and raffle, started at $99, paid to the event’s organizer, the San Diego County Gun Owners PAC. People carrying glasses of wine browsed a selection of NFL and Taylor Swift memorabilia up for bid and dropped tickets into white-paper-covered boxes for a chance to win a camo-print hunting rifle or a tactical bullpup shotgun painted red, white and blue.

Michael Schwartz, the PAC’s executive director, described the event as a way to have fun with like-minded people and raise money for pro-gun advocacy. But it’s also a forum for animated commiseration about the state of gun regulation in California.

To Schwartz, Gilreath’s experience is evidence that the process of opening a gun dealership is too onerous.

“California has gone too far. The amount of time and paperwork is totally crazy,” he said. “They’re trying to stop criminals by making it difficult for law-abiding gun dealers to exist. I think that municipalities … shouldn’t be able to keep a business out just because it” sells guns.

A little after 7 p.m., the attendees made their way to their tables. Before dinner, they rose for “The Star-Spangled Banner.” And they rose again for a roaring recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance.

The Gun Prom’s queen was introduced via prerecorded video, standing in the desert in a shiny blue dress, white sash and tiara. The teenaged competitive shooter ticked off five rules for gun owners.

After she declared the final one — “Never let the government take your guns!” — the video erupted in a blast of AC/DC and gunfire as she took target practice with a modified handgun.

For Megan Oddsen, the challenge is keeping new gun stores out of town.

In the wake of last year’s mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, she and a tightknit crew of Culver City film industry types, designers and stay-at-home parents founded a local advocacy organization called Culver 878.

The group’s chief objective was to find ways to curtail firearm sales in the city. Its white whale was the Martin B. Retting store, which had sold guns and ammunition for 65 years on a busy stretch of Washington Boulevard. The 878 in the group’s name is a reference to one way of calculating the number of feet between the retailer and the nearest elementary school.

“We started organizing after Uvalde around a long-standing anxiety that people in our community have had about Retting,” Oddsen said last year.

Since 2005, Culver City has had an ordinance barring gun sellers within 1,000 feet of primary and secondary schools, parks and playgrounds. But because Retting was already in operation, it was grandfathered in and was not subject to the buffer zone. Municipal officials told the group that the city couldn’t force the dealer to move.

So Culver 878’s members got creative. One afternoon in October 2022, half a dozen met on the patio of a cafe up the block from Retting to lay out an ambitious vision.

“There’s a discrepancy between thousands of people walking by the store and seeing guns and everything, and then our kids at school down the street are doing active shooter training,” said Karim Sahli, a Culver 878 member and father of two.

The activists compiled a list of more than a dozen ordinances they wanted the council to pass. They included relatively minor regulations and bold proposals such as scaling back longtime firearms dealers’ grandfather rights to operate near schools.

But first they consulted with the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. The national advocacy organization talked them down from pursuing some of the strictest measures, citing the likelihood that pro-gun groups would sue if the city were to institute them.

“We settled on these regulations because they felt that they were safe to enact here and would not be as risky as far as a lawsuit,” said Oddsen, who is also on the board of the L.A.-based Women Against Gun Violence. “These were a huge compromise for us. We wanted the store to relocate.”

Allison Anderman, senior counsel and director of local policy at the Giffords Law Center, said it was the prudent approach.

“There are sometimes local activists who aren’t particularly sophisticated on this issue who just say things, like, ‘I want to ban all gun dealers,’” she said. “Our approach on that is that’s not necessary. … We advise jurisdictions based on what we think, given existing law and precedent, is reasonable.”

In December 2022, the City Council approved a slate of regulations requiring gun dealers to obtain local permits, purchase liability insurance, post additional safety warnings and submit to regular city inspections.

But Retting would still be allowed to sell guns in the heart of Culver City.

Martin B. Retting was never a low-key operation.

Its facade was emblazoned with a massive image of an old-fashioned lever-action rifle resting on the word “GUNS” in big, bold lettering. Each year, it sold thousands of firearms within one block of a public park, a mosque and two Christian congregations.

Many cities’ zoning codes impose additional restrictions near places that chiefly serve children, such as schools, day care centers and parks. For example, a 2016 study found 51 municipalities in California that restrict tobacco sales near schools. More than 20 California cities, including Culver City, ban gun dealers within various distances of campuses.

Despite Culver City’s attempts to regulate dealers, its gun shops have had an outsize role in feeding crime.

Of the five municipalities where dealers sold the most crime guns recovered in Los Angeles between 2017 and 2021, the top two were Las Vegas and Phoenix, selling 1,097 and 820, respectively, according to a February report by the ATF. A June report by the state Department of Justice cites the California Penal Code to define crime guns as “recovered firearms that are illegally possessed, have been used in a crime, or are suspected of having been used in a crime.”

Next on the list were Torrance and Culver City, two comparatively small cities in L.A. County.

Between 2017 and 2021, the ATF report said, more than 700 crime guns recovered in L.A. were purchased in Torrance, a city that had 18 licensed dealers as of November. Culver City’s firearms dealers were the source of 589 crime guns recovered in L.A.; as of November, the ATF’s list of federal firearms licensees counted four in the city, including Retting.

Just 82 dealers sold about half the crime guns that originated and were recovered in California between 2010 and 2022, according to the June state Department of Justice report. Forty percent of those dealers sold crime guns at a higher rate than average, the Times analysis found. Dr. Garen Wintemute, director of the Violence Prevention Research Program at UC Davis, calls these outliers “bad-guy magnets.”

“They’re more likely than others to sell guns used in crime. So you want to go after them,” he said.

Retting sold 1,019 crime guns between 2010 and 2022 that were later recovered statewide. That’s the ninth-highest tally of any California dealer — and 1.5% of the more than 69,000 firearms Retting sold over the period.

In a 2015 inspection, an ATF investigator issued Retting seven violations for infractions including failure to report multiple sales of handguns, verify buyer identity and collect complete and verified sales forms.

The Times first requested information about more recent inspections from the ATF in August 2022 but has yet to receive the information.

Martin B. Retting’s owners did not respond to repeated requests for comment. An employee padlocked a metal gate between the shop’s glass front door and its sales floor when approached by a reporter in September.

Asked if someone was there who could answer questions, the employee, who spoke through the gate with a barrel-down shotgun in hand, went to a back room and came back to say that “one of the owners” said “the answer is no comment.”

Asked if the owner could speak even briefly with The Times, the employee gestured toward the street.

“You’ve already overstayed your welcome.”

Over the summer, word came Retting was closing down.

A letter dated July 16 was posted on the store’s website announcing that its final day of full operation would be July 31, but it would remain open for some time afterward for used firearm purchases and other limited purposes.

The letter said the closure was “not a liquidation, clearance or distress sale,” and the company was not facing financial difficulties.

“There’s really nothing to read into the retirement and our closing other than the fact that the owners are well past the age where most folks have already been retired for a while,” the letter stated.

At first, local gun control advocates were ecstatic. But that sense of triumph quickly turned to steely determination when they learned Culver City’s code provided for a grandfather period during which Retting could transfer to a new tenant the rights to sell guns out of the building on Washington Boulevard.

“Basically, we wanted to eliminate any possibility of another gun store opening there,” Oddsen said.

So, she spent late nights trying to find a legal mechanism to prevent a new gun seller from moving in. The group’s members reached out to officials and neighbors, sent fervid emails and posted about the issue on social media.

On Aug. 28, the Culver City Council held a hearing on the future of the Retting building and whether to impose a 45-day moratorium on gun dealers’ rights to transfer properties to new dealers while it decided how to proceed.

But there was never a vote on the moratorium.

In a closed-door session three days later, Culver City officials met with Dan Retting to negotiate a deal for the building. On Sept. 11, the council unanimously voted to buy the property for $6.5 million.

City officials said the building will be repurposed for another, presumably less controversial, use.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.