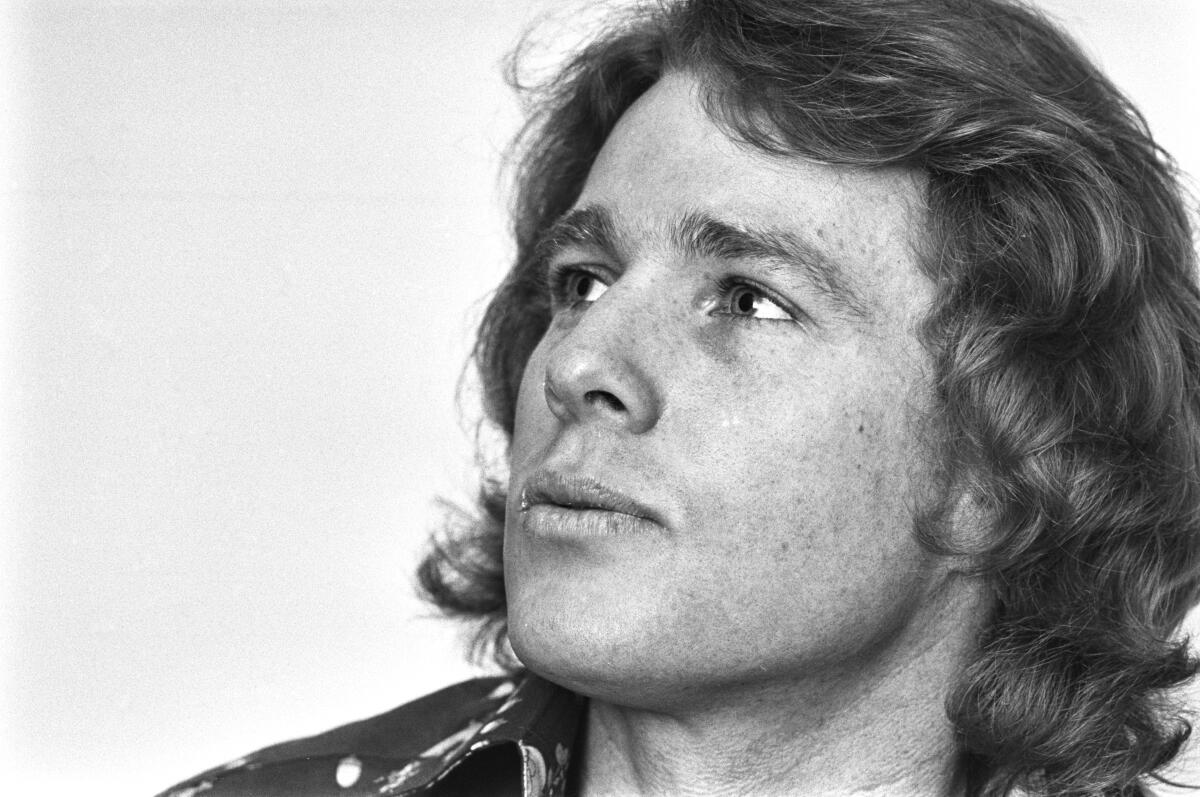

Ryan O’Neal, star of ‘Love Story’ and ‘Paper Moon,’ dies at 82

Ryan O’Neal, who starred in “Love Story” and “Paper Moon,” cementing his status as a heartthrob in the ‘70s, died Friday. His death on Dec. 8 at Saint John’s hospital in Santa Monica was confirmed by his son, Patrick O’Neal. He was 82.

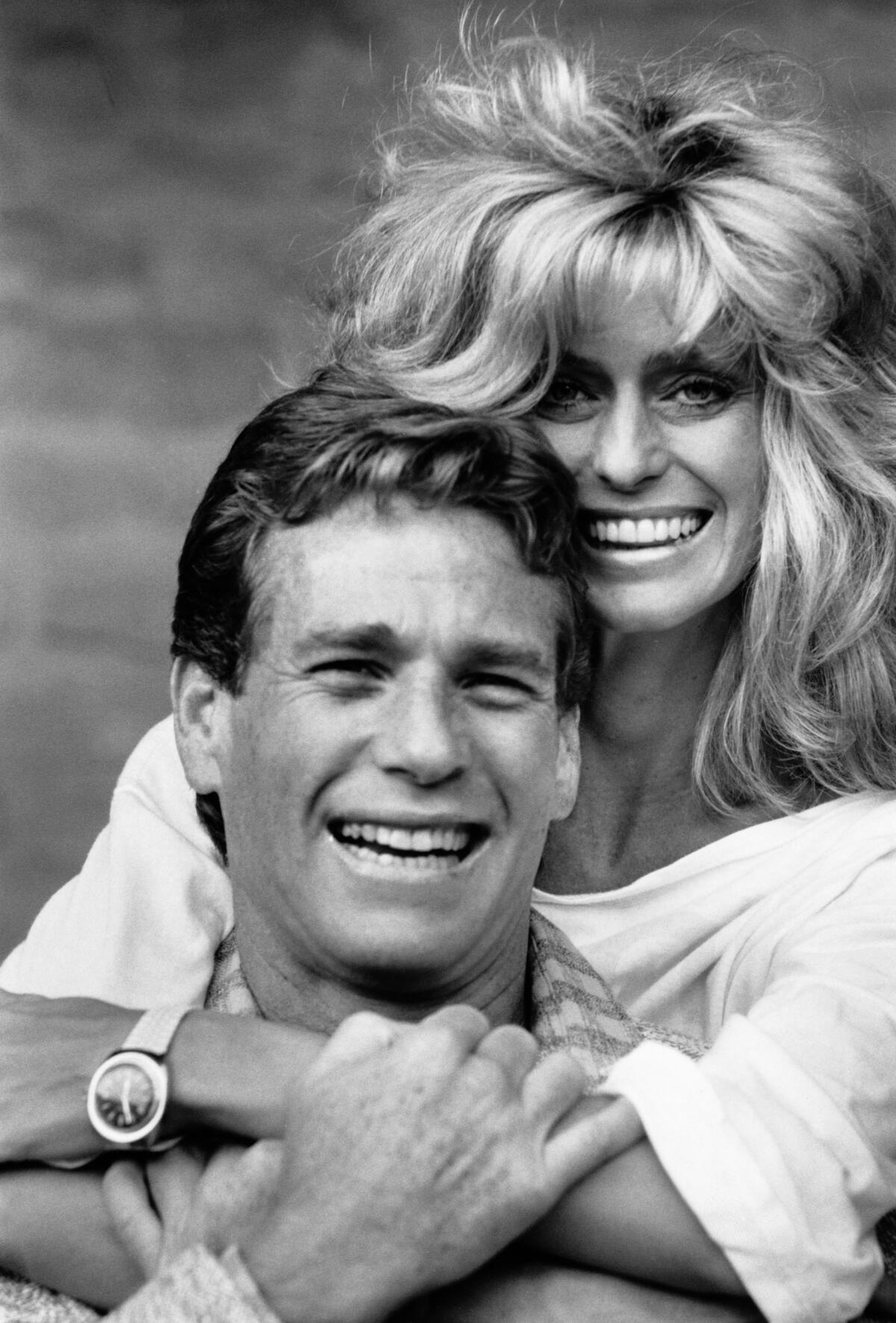

He emerged as a heartthrob on television’s “Peyton Place” in the 1960s and arrived as a movie star in the sentimental 1970 box-office hit “Love Story.” Yet O’Neal achieved his most enduring fame off-screen, as the longtime companion of actor Farrah Fawcett, who died of a rare form of cancer in 2009, and father of four whose turbulent family drama often landed in the headlines.

After O’Neal was nominated for an Academy Award for portraying a preppy, star-crossed lover in “Love Story,” Bob Hope introduced him at the Oscars as Hollywood’s “leading boy,” a reference to O’Neal’s clean-cut good looks and relative youth. He was not quite 30.

When major long-term success eluded him, agent Sue Mengers theorized that her client’s romance with sex symbol Fawcett had helped sink his acting career: Together they were too Hollywood, too perfect, “Barbie dolls” who took your breath away. Others suggested his volatile nature was to blame.

Once O’Neal and Fawcett started dating in 1979, their stormy on-again, off-again relationship spanned the rest of her life. She returned to O’Neal’s side in 2001 when he was diagnosed with leukemia, and he was there for Fawcett during her three-year cancer battle that ended with her death at 62 in 2009.

O’Neal died Friday, his son Patrick announced in an Instagram post. Ryan O’Neal revealed that he had prostate cancer in 2012.

“My dad passed away peacefully today, with his loving team by his side supporting him and loving him as he would us,” the actor and sportscaster wrote Friday. No cause of death was given.

Patrick O’Neal, Ryan O’Neal’s only child with fellow actor Leigh Taylor-Young, recalled his father as a “Hollywood legend” and an actor “skilled at his craft,” who could memorize “pages of dialogue in an hour,” and as a humble, “generous” person. He recalled moments with his father on set as a child, watching him interact with crew members whom O’Neal loved and who “loved him” back.

“Ryan never bragged,” Patrick O’Neal continued. “But he has bragging rights in Heaven. Especially when it comes to Farrah. Everyone had the poster, he had the real McCoy. And now they meet again. Farrah and Ryan.”

A rare cancer claims the 1970s pinup beauty. First known for her looks and hairstyle, she captivated critics with ‘The Burning Bed’ and other serious roles. Later, she chronicled her illness.

“He’s had a strange career, but he was a monster star,” Paul Mazursky, who directed O’Neal in the 1996 comedy film “Faithful,” told Vanity Fair in 2009. “He’s sweet as sugar, and he’s volatile ... but he’s a good guy, and he’s very talented.”

In 1964, O’Neal began to break through on “Peyton Place,” the first soap opera to become a major prime-time hit. He played the wealthy Rodney Harrington alongside Mia Farrow, who was the show’s other famous discovery. She left early on, but O’Neal stayed for virtually the show’s entire five-year, 500-plus episode run.

“Love Story” director Arthur Hiller chose O’Neal from more than 300 actors to play Oliver Barrett IV, who falls for Ali MacGraw’s character, a feisty co-ed who meets an untimely soap opera-esque death. Both lead actors uttered the movie’s most famous line, which became a national catchphrase: “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

Even reviewers who winced at “Love Story’s” tearjerker plot conceded that O’Neal’s performance “makes the film almost tolerable,” according to a 1971 Life magazine profile of O’Neal that ran beneath the headline “A Very Brash Young Man.” He had already served more than 50 days in jail for assault and battery at the time.

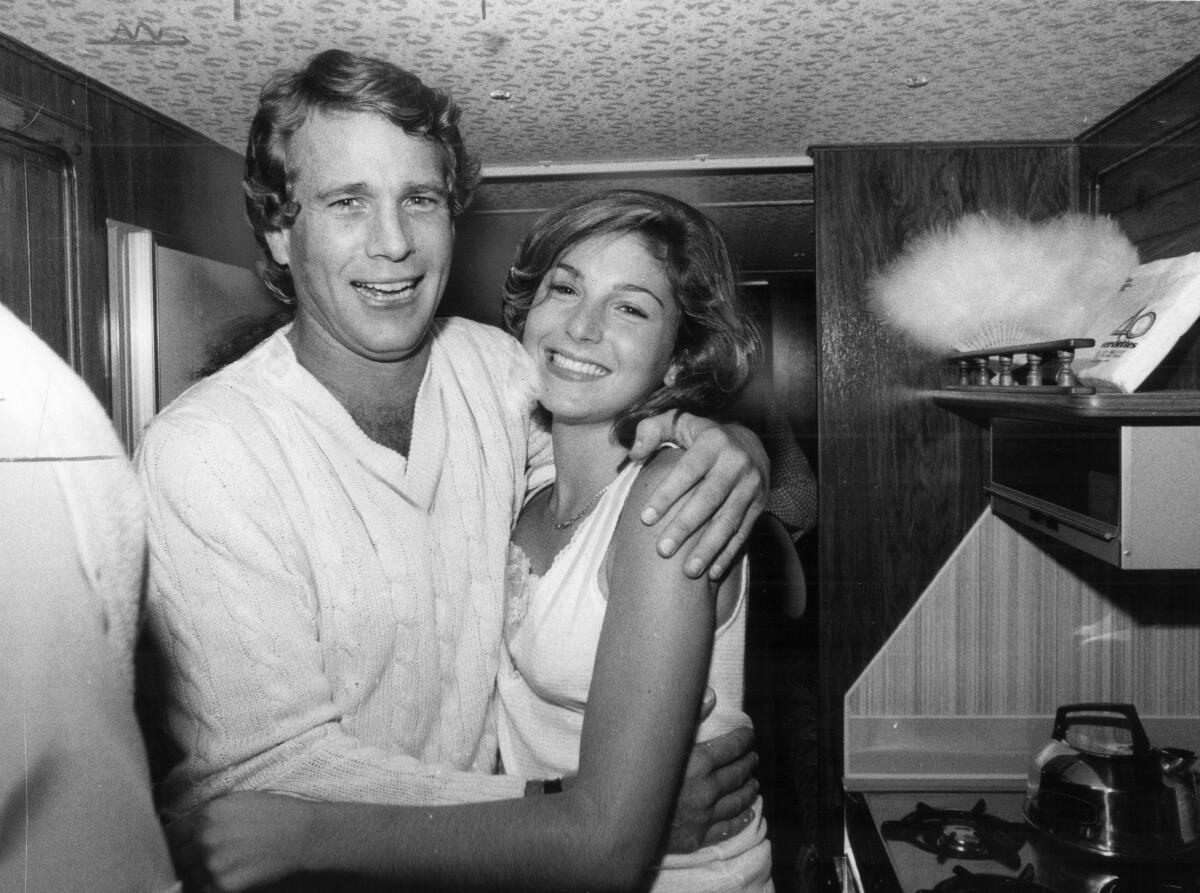

He stood out in the early 1970s in two films by director Peter Bogdanovich, “What’s Up, Doc?,” a romantic farce that also featured Barbra Streisand, with whom O’Neal was having an affair; and “Paper Moon,” a charming black-and-white comedy about an exasperated con man and his daughter, played by O’Neal’s real-life offspring, Tatum.

When Tatum received an Oscar for the 1973 role, she became the youngest person to win a competitive Academy Award. Neither of her parents was in the audience to witness the 10-year-old’s triumph, an early public display of the family’s dysfunction.

Her mother, actor Joanna Moore, struggled with drug addiction, and her father was jealous that Tatum stole his thunder on “Paper Moon,” Tatum said years later. He blamed his daughter’s Oscar for causing family tension. “Everybody hated everybody because of that Academy Award,” he said in the 2009 Vanity Fair profile.

O’Neal’s next film, 1975’s “Barry Lyndon,” should have established him as a serious actor. Instead, the Harvard Lampoon dubbed him “the worst actor of the year” for his role as the 18th century rogue at the center of writer-director Stanley Kubrick’s slow-paced epic. The film failed at the box office, but is now seen as one of Kubrick’s more formidable achievements.

Years later, O’Neal told Vanity Fair: “I never got a good job after it. I didn’t have an image.”

He was in his mid-30s, and his career had already peaked.

“There aren’t many legends left,” I tell the veteran actor, saying that it’s an honor to meet him.

Hollywood observers began to characterize him as pompous, vain, surly and overly macho, “a product of the Southern California sun-worshiping lifestyle masquerading as an actor,” according to a 1977 Times article.

His string of movies between the late 1970s and early 1990s included “Oliver’s Story,” a dismal “Love Story” sequel; “The Main Event,” a labored farce that reteamed him with Streisand; and “Irreconcilable Differences,” a comedy-drama co-starring Shelley Long that fared better with critics.

At some point he stopped trying as an actor, O’Neal once admitted, a sentiment that may have applied to his personal life as well.

While promoting “Both of Us,” his 2012 memoir about life with Fawcett, O’Neal seemed dispirited on the “Today” show when asked if he was a bad parent. He responded: “I suppose I was.”

“I can’t help but wonder how someone raised in a stable and loving environment could have ended up making such a mess of his own family life,” O’Neal wrote in his memoir.

He was born Charles Patrick Ryan O’Neal on April 20, 1941, in Los Angeles, the eldest of two sons of Charles O’Neal, a B-movie screenwriter, and his actor wife, Patricia. His brother Kevin also became an actor. Much of O’Neal’s childhood was spent abroad, where his parents found work.

An amateur boxer in his youth, O’Neal’s first job in show business was as a stuntman on a German TV series. After returning to the U.S., he was cast in 1962 in the short-lived television western “Empire.”

By the early 1960s, O’Neal and his private life were under the media microscope. Photographs of him with Moore and their young children — Tatum and Griffin — were fan-magazine staples.

After actor Taylor-Young joined “Peyton Place” in 1966, O’Neal separated from his wife of three years and married Taylor-Young in 1967. They had a son, Patrick, before divorcing six years later.

“In the old days, there wasn’t one woman in Ryan’s life — there were hundreds,” Mengers told Vanity Fair in 1991.

Fawcett entered his life when her husband, actor Lee Majors, asked his buddy O’Neal to check up on her while Majors was on location. Fawcett was soon staying at the oceanfront home in Malibu that O’Neal bought for $130,000 in the early 1970s from director Blake Edwards.

O’Neal openly admitted he largely went missing as a parent after that.

“My family was fractured,” Tatum wrote in her 2011 book “Found: A Daughter’s Journey Home,” a title she said was “wishful thinking.” Life with the O’Neals was “a stew of drama, drugs, violence and tragedy,” wrote Tatum, who struggled with heroin addiction.

In 1985, O’Neal and Fawcett had a son, Redmond, who has been in and out of drug-treatment programs and jail or prison since he was 13. When O’Neal and Fawcett had a major breakup in 1997, she attributed it to conflicts over parenting. He later wrote that she had walked in on O’Neal with a young actor with whom he was having an affair.

“They were dynamic, strong-willed people who often clashed,” longtime friend Alana Stewart said of O’Neal and Fawcett in 2012 in USA Today. “But they had this deep connection and a deep love.”

Shortly before Fawcett died, O’Neal said he and Fawcett were planning to marry. “We had a rhythm that worked, but I’m hard to live with,” he said on “Today.”

Snapshots of his personal life were often unsettling. He got into well-publicized fights with his sons, knocked out two of Griffin’s teeth when he was a teenager and, in 2007, fired a gun at him. The next year, O’Neal and Redmond were both arrested for possessing methamphetamines.

Redmond was in jail on attempted murder charges when he was allowed to attend his mother’s funeral, where his father flirted with someone he called “a beautiful blond woman” until she said, “Daddy, it’s me — Tatum!” He cast the interaction as an “innocent private joke.”

Of his four children, only sportscaster Patrick O’Neal has been untouched by drugs and serious problems and has retained a stable relationship with his father.

In addition to his four children, O’Neal is survived by eight grandchildren.

With Fawcett, O’Neal appeared in the 1989 television movie “Small Sacrifices” and the 1991 sitcom “Good Sports.” More recently, he had a recurring role on the TV drama “Bones.” He also battled a slew of ailments — diabetes, leukemia, prostate cancer and a bad heart.

He was, however, a steady presence in the Emmy-nominated stark video diary that Fawcett kept about her struggle with cancer that aired in 2009 on NBC as “Farrah’s Story.”

In another unscripted television show, “Ryan and Tatum: The O’Neals,” father and daughter were presented in 2011 as trying to repair their damaged relationship. Both were “funny, fierce and unapologetically warped,” according to The Times review.

But the rapprochement, O’Neal later said, was only for the cameras.

Times staff writer Jonah Valdez contributed to this report.

It's a date

Get our L.A. Goes Out newsletter, with the week's best events, to help you explore and experience our city.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.