Robbie Robertson was on the verge of his greatest success with Martin Scorsese

This article was not supposed to be an appreciation. I was literally hours away from interviewing Robbie Robertson for a celebratory feature about his most impressive film score, for the forthcoming “Killers of the Flower Moon,” and his long and varied collaboration with its director, Martin Scorsese, who was also going to answer some of our questions. The gods had other plans.

Robertson, whose mother was born on the Six Nations Reserve near Lake Erie in Canada, breathes and strums a windstorm of personal expression into the film’s staggering score, which Scorsese cranks noticeably loud in the mix. It pounds along with the beat of drums and shakers, chords splashing on acoustic and electric guitars, accented with banjo twangs and the birdlike cries of various flutes.

Robertson’s contribution is an astonishing and lively musical ecosystem that gives immediate authenticity to Scorsese’s equally vivid presentation of Osage life and culture in 1920s Oklahoma. It’s music that proudly worships and dances with these people — and alternately weeps for their oppression, at times sounding almost sick at their treatment by the story’s white predators.

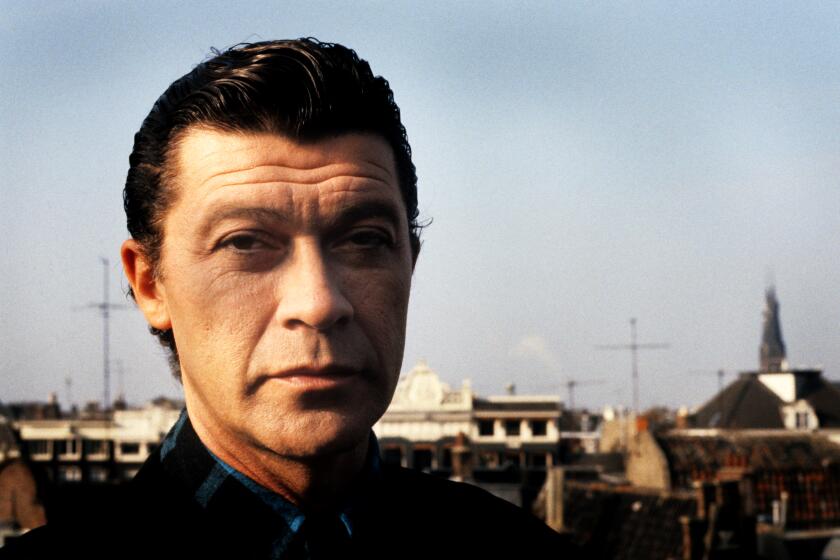

The movie was the pitch-perfect canvas for Robertson’s gifts — not just his Native ancestry but also his rootsy songwriting DNA and skills as a musical storyteller. When the movie comes out in October, it will be the last film he ever scored. Robertson died Wednesday at age 80.

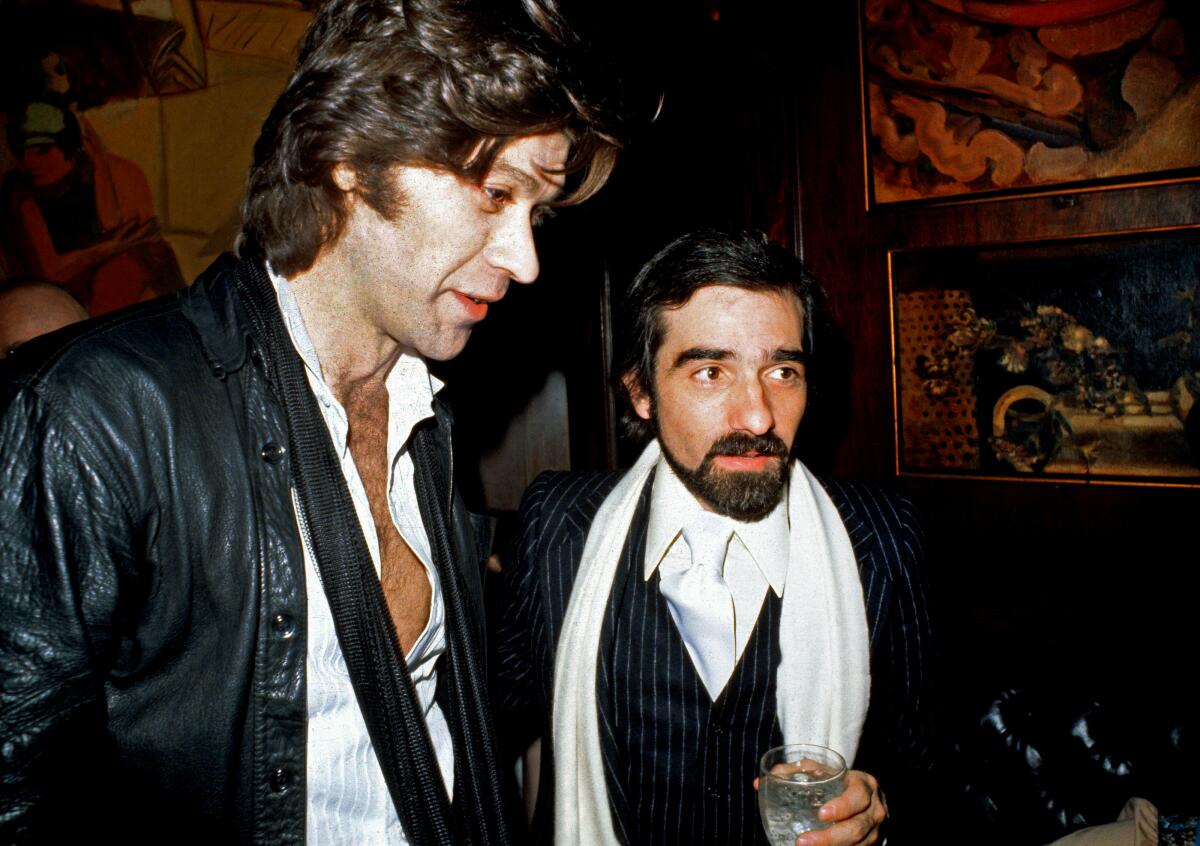

Scorsese spotted that skill right away when he first locked arms with Robertson in 1976. In “The Last Waltz,” the director cinematically captured the star-studded farewell performance of the Band, Robertson’s virtuosic outfit that shared a constellation with Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and a dozen other 1960s legends who joined them onstage that night.

Scorsese not only interviewed Robertson and his bandmates but also coordinated every lyric and shot with Robertson as though it were a choreographed musical. The songwriter also produced the picture, and in his onscreen chats with the director, he comes off like a scruffy, charismatic character out of one of Scorsese’s early movies, maybe “Mean Streets.”

“Each time we went out to do a number and a concert, it was like doing a round in a prize fight,” Robertson says in the film.

“Now, this automatically triggered something in me,” Scorsese told the Hollywood Reporter in 1978 about the line. “It’s like ‘Mean Streets.’ I began to understand the characters a little more. Because nobody ever knew the Band. They had this aura about them that you couldn’t go near. And I began to talk to them and I began to realize what kind of guys they are, and the pain they go through every time they sing a song. That’s what I wanted to capture.”

Hollywood came calling, and Robertson was cast as a lead in the 1980 film “Carny,” which he also produced. But he was much more at home in the studio and on the soundtrack, and he quickly became Scorsese’s wingman in all things music.

“It’s never been about traditional movie music,” Robertson told Headliner in 2019 about that role.

Scorsese has often used rock and pop songs in place of scoring throughout his prolific film career — it was the “soundtrack of his life,” he has said, the music that was pouring out of apartments and car windows in the background of his own story. After “The Last Waltz,” he deputized Robertson to be his music consultant and soundtrack supervisor.

Starting on “The King of Comedy,” the 1982 cringe-comedy classic starring Robert De Niro that was recently replicated in “Joker,” Robertson helped curate and produce songs for numerous Scorsese films. He would often contribute a song or two himself, and where an occasional instrumental score cue was needed, he would supply that as well.

On “The Color of Money,” Scorsese’s sequel to “The Hustler” starring Paul Newman and Tom Cruise, Robertson conceived a fitting barroom jukebox soundtrack, teaming up with blues legend Willie Dixon and arranger Gil Evans. Robertson couldn’t read or write music, so he recorded tapes of himself humming for Evans to translate for an orchestra. He also sent the tapes to Scorsese, “and he put it in the movie,” Robertson recalled in 2019.

“I said, ‘No, that doesn’t go in the movie. That’s me just composing in my kind of way. We’re going to do that with the orchestra.’ And he said, ‘Oh, no, it works really well.

“From then on,” Robertson quipped, “I’ve been careful about what I send him.”

The anecdote is revealing of their playful, unorthodox partnership, which continued from “Casino” through 2019’s “The Irishman.” Scorsese would frequently work with conservatory-trained film composers to write more traditional scores: Howard Shore, also a Canadian, was a favorite. But for his sprawling, multi-era tale of an Irish American mobster, the director wanted some of Robertson’s distinct magic.

A look back at the best of Robbie Robertson, the pioneering Band songwriter and guitarist who died on Wednesday at 80.

The musician went looking for a “haunting mood,” he told Headliner, and came up with an ambling death march for blues harmonica and ink-black bass. His score provided the glue between a needle drop soundtrack that featured Glenn Miller and Fats Domino. The picture ends with an original song, “I Hear You Paint Houses” — a nod to the Charles Brandt book that inspired the movie — with Van Morrison singing the phrase and Robertson repeating it.

It would have been a fitting coda to the four-decade duet between Robertson and Scorsese, but then the filmmaker made a stunning late-career masterpiece based on the 2017 book “Killers of the Flower Moon” by David Grann and gave Robertson his most prominent and poetic role in any scoring assignment he’d ever taken on.

The resulting music, so rich in mood and melody — teeming with the terroir of Turtle Island and the first ill-fated Americans who sang and danced with spirits — is the best music Robertson ever wrote for the screen. It’s not fair that he didn’t live to experience its reception, but it couldn’t be a finer eulogy for a chief American musician.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.