The virus first struck Leonardo Miranda, who rented a shed and shared the kitchen, bathroom and dining room in the main house.

It spread to a man who slept on three red cushions in the laundry room. Then to a grandfather and grandson who wedged two mattresses into one room. By the time COVID-19 was finished with the three-bedroom home, shared by eight, Miranda and the grandfather were dead.

Miranda’s death in January 2021 would become part of a calamitous pattern. Los Angeles’ most overcrowded neighborhoods have experienced COVID-19 death rates that are at least twice as high as those with ample housing.

This public health disaster was the inevitable consequence of more than a century of decisions that resulted in L.A. growing more like an endless suburb than a towering city.

At the heart of the storied metropolis of single-family-home sprawl, L.A. leaders created a cruel paradox: It is also the country’s most crowded place to live.

More homes are overcrowded in Los Angeles than in any other large U.S. county, a Times analysis of census data found — a situation that has endured for three decades, with no sign of abating.

In places like the Pico-Union neighborhood, where Miranda lived, generations of families squeeze into tiny apartments. Construction workers, seamstresses and dishwashers live in close quarters. Day laborers bunk with half a dozen or more strangers in living spaces intended for one or two people.

Within these confines, COVID-19 advanced without mercy: orphaning children, killing breadwinners and shattering families.

L.A.’s leaders could have addressed deplorable living conditions for the region’s poorest residents with more apartments, taller buildings and public housing. But they saw those ideas as anathema to the Southern California lifestyle they were creating. So in working-class neighborhoods, more and more people crammed into the existing housing stock, particularly as new streams of immigrants came from Mexico and Central America.

Repeated warnings about the consequences of such unprecedented crowding — for public safety, disease control, schools, urban services, sanitation — were ignored.

To understand the contradiction underlying L.A.’s status as the nation’s capital of both crowding and sprawl, The Times reviewed historical archives, oral histories and newspaper accounts, analyzed decades of U.S. census data and conducted dozens of interviews with academic experts, public officials, residents of cramped apartments and people whose family legacies in the region date back more than a century. What emerged was a singular thread tying civic leaders’ decisions from the founding of modern L.A. to today’s living conditions.

In the late 19th century, the city’s railroad magnates and newspaper publishers began promoting Southern California as a slice of paradise and encouraged white Americans to come buy a piece of the dream.

The promise of Los Angeles was bright winter sun; clean, dry air; single-family homes with lawns in front and orange trees in back; and panoramas of mountains and sea. It lured millions from dark, big-city tenements and cold Midwestern farms to the new suburbs.

To bring the vision to fruition, business leaders recruited Mexican laborers en masse to build rail lines, houses and schools; pick crops; clean homes; and work in slaughterhouses, sugar-beet refineries and steel plants. But racist real estate rules and low pay sequestered Mexican workers and their families in cramped, often pestilent shacks, where deadly tuberculosis spread just like COVID-19 has today.

In the middle of the 20th century, L.A. leaders bulldozed Mexican neighborhoods in Chavez Ravine, forcing out thousands with the promise of new, low-cost, public housing to meet the needs of a city exploding in population after World War II. Then real estate interests exploited the communist paranoia of the Red Scare to defeat the housing projects, and instead, the city gave the land to the Dodgers for a stadium to entice the team’s move from Brooklyn.

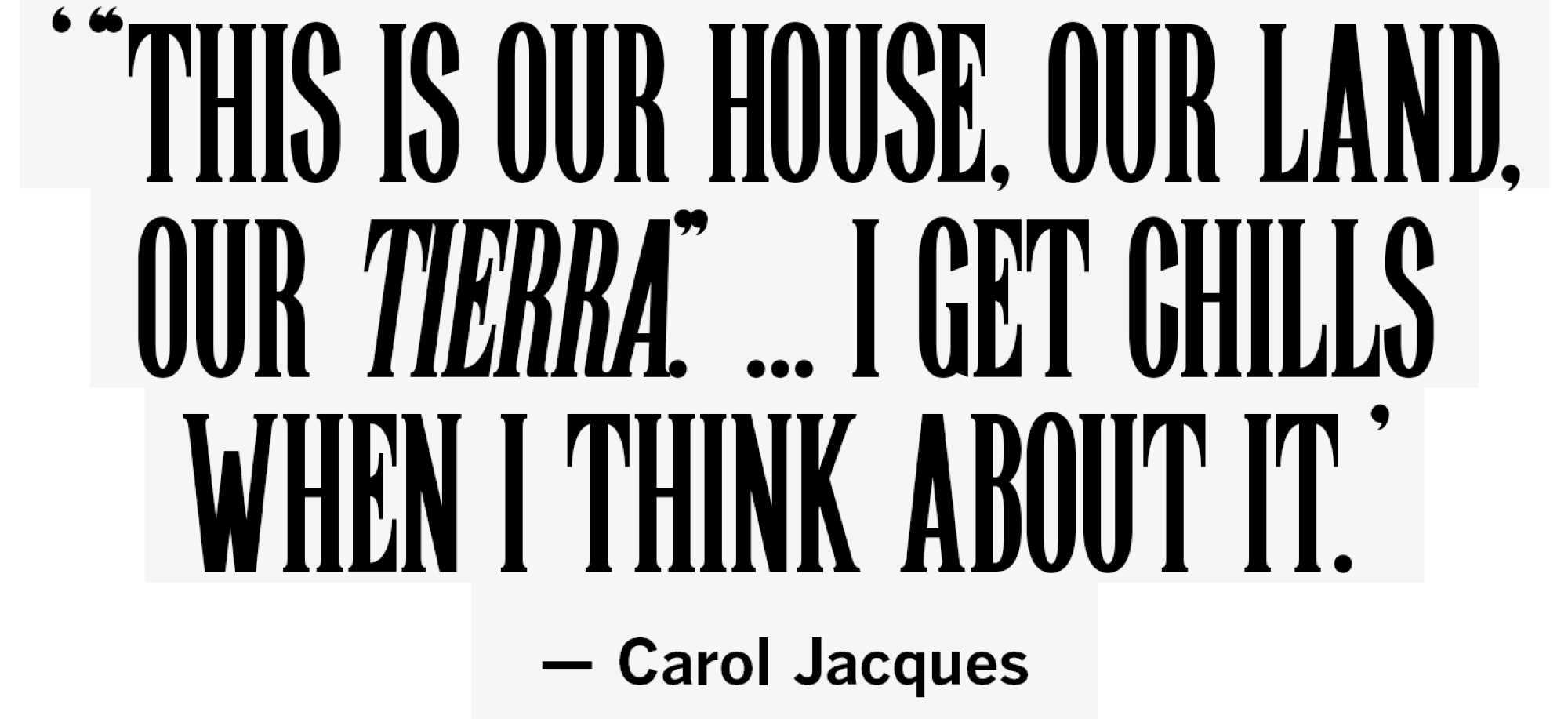

“We had affordable housing,” said Carol Jacques, 79, who grew up in Chavez Ravine and lost her family home. “We had the opportunity to do generational wealth building and have us do better.”

By the 1970s, “slow growth” fervor, combined with a diminishing supply of new land to develop, spelled the beginning of the end of L.A.’s home-building booms. This change happened just as Mexican, Guatemalan and Salvadoran immigrants were pouring into the region to work, leaving them no choice but to pack into low-rise slums and hastily converted garages. In recent decades, as immigration has waned, skyrocketing housing costs have locked generations of Latino families into grim cycles of overcrowding.

For many, living in crowded spaces and sharing the burden of unaffordable rents has become the last line of defense against joining L.A.’s ever-swelling homeless population.

Overcrowded homes have left scores dead in horrific fires and, studies have shown, stunted children’s health and achievement in school. But more than any other calamity, the pandemic exposed how vulnerable Los Angeles is to mass outbreaks of communicable diseases.

Across the country, political and public health leaders have long known about these dangers.

The infamous examples of overflowing apartments, such as 19th century tenements in New York City, are mostly relics. A Times analysis of census data shows that 3% of U.S. homes are overcrowded, defined by the federal government as having more than one person per room, excluding bathrooms.

Aerial view of the Pico-Union neighborhood in Los Angeles. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In Los Angeles, the overcrowding rate is 11%. In Pico-Union, it is 40%, making the community just west of downtown one of the most crowded in the country. Some 40,000 people live in its 1.33 square miles — a population density that surpasses New York City’s, without a skyscraper in sight.

Here, people rent spots to sleep on the floors of laundry rooms. Teenagers do homework in alcoves outside apartments. Families use the bathroom in shifts.

There is nowhere to hide when an infectious disease strikes.

There have been more than 15,500 COVID-19 cases recorded in Pico-Union, and nearly 300 people have died of the disease, one of the county’s highest death rates. Pico-Union residents have been 11 times more likely to die from COVID than those living in Manhattan Beach, a similarly sized, predominantly white and wealthy community where just 1% of homes are overcrowded, according to a Times analysis of public health data.

While other reasons also are at play — poor underlying health, less access to medical care, more essential workers who can’t work remotely — these often come alongside overcrowding and stem from the original inequity of a society relying on low-paid labor.

It’s not just Los Angeles. Studies of New York City, the Bay Area, Chicago and Washington, D.C., among other urban areas, have found that overcrowded housing is driving viral spread and COVID deaths.

“What’s astounding for everyone is to be able to see in a very short time frame with COVID the impact of overcrowding,” said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer.

Miranda, a construction worker, got sick with COVID in December 2020, as cases were rising across the city. The 62-year-old had no choice but to go inside the main house to use the bathroom and other shared spaces.

One of the three housemates to whom Miranda spread it, 67-year-old Yelman Oviedo, died in the hospital 15 days after he did. Oviedo’s wife, Vicky Escalante, moved out of the bedroom they shared with their 18-year-old grandson. It was traumatic for her to be there, and she felt her grandson needed privacy. Now she sleeps on a small couch in the living room. With two fewer people helping with the rent, she’s worried about falling behind.

“If I move from here,” Escalante said, “where am I going to find a place?”

The vision of Los Angeles first had to be sold in order for it to be built.

After the Civil War, arrivals from the East began to imagine a great new city rising from the scrub. The actual Los Angeles was a fly-ridden settlement of tumble-down adobes, packs of feral dogs and one of the nation’s highest murder rates. Despite the reality, these emerging oil, railroad and publishing magnates saw an Arcadian paradise for the masses.

The promise was a life that left behind the congested ills of urban living and the severity of rural life and instead delivered the best of both. Like the finest metropolis, L.A. would have playhouses, a modern economy, gleaming libraries, schools, an urban rail system and a first-rate seaport. These amenities would come with the healthful allure of the countryside. Angelenos would have their own slice of nature — lawns, gardens and fruit trees — surrounding their detached, single-family houses.

At the very heart of this promise was liberation from the density that characterized East Coast cities; tall tenements for the poor weren’t part of the dream.

“Los Angeles, as a city of homes, will become more and more desirable every year,” read an 1886 editorial in The Times. “They will be an earnest of her moral and intellectual growth, and all of her industrial relations, her general development and commercial importance will not fall behind the increase of her homes. They will grow together, and the result will be altogether desirable.”

The sales pitch was working: L.A. had just entered its first population surge. In 1880, L.A. County had fewer than 35,000 people. Ten years later, the population had tripled. Over the next two decades, it grew another fivefold.

This explosive expansion encouraged oil barons, real estate tycoons, Chamber of Commerce executives and The Times to push for more. Through newsreels, billboards, postcards, songs, cartoons and newspaper ads, they sent one overriding message to the rest of the country: Come.

“Here where Nature has builded her finest playground, man has added the material things which provide the comforts that make life worth while,” proclaimed a 1921 advertisement in The Times titled “The Great Southwest.” “Thousands upon thousands have come to enjoy life in the mountains, near the sea, in the citrus groves and amid the forever blooming gardens, yet but a fraction of the resources of this wonderful country has been developed.”

Forever underlying the promise of Los Angeles were decisions by powerbrokers — notably, the Chandler family that owned The Times — on who should have a piece of this land of plenty. Celebrating at a swanky downtown hotel in the mid-1920s, the city’s business titans attributed their success to “the enormous and persistent influx of desirable persons from all parts of the country into Los Angeles,” according to a Times account of the gathering. This, one of the evening’s speakers proclaimed, ensured that L.A. had become “America’s white spot,” while everywhere else had turned “dark.”

When others came to L.A. — the Chinese railroad workers, the Black sharecroppers escaping the brutality of Jim Crow, the Mexican bricklayers fleeing revolution and the dissolution of their rural economy — the response was exclusion. Many were relegated to the exact type of crowded slum conditions that Southern California’s leaders had railed against in their grand sell.

For decades, racially restrictive covenants prohibited Asian, Black and Latino families from living in the new subdivisions. A 1925 ad in The Times touted that “the residents of Eagle Rock are all of the white race.”

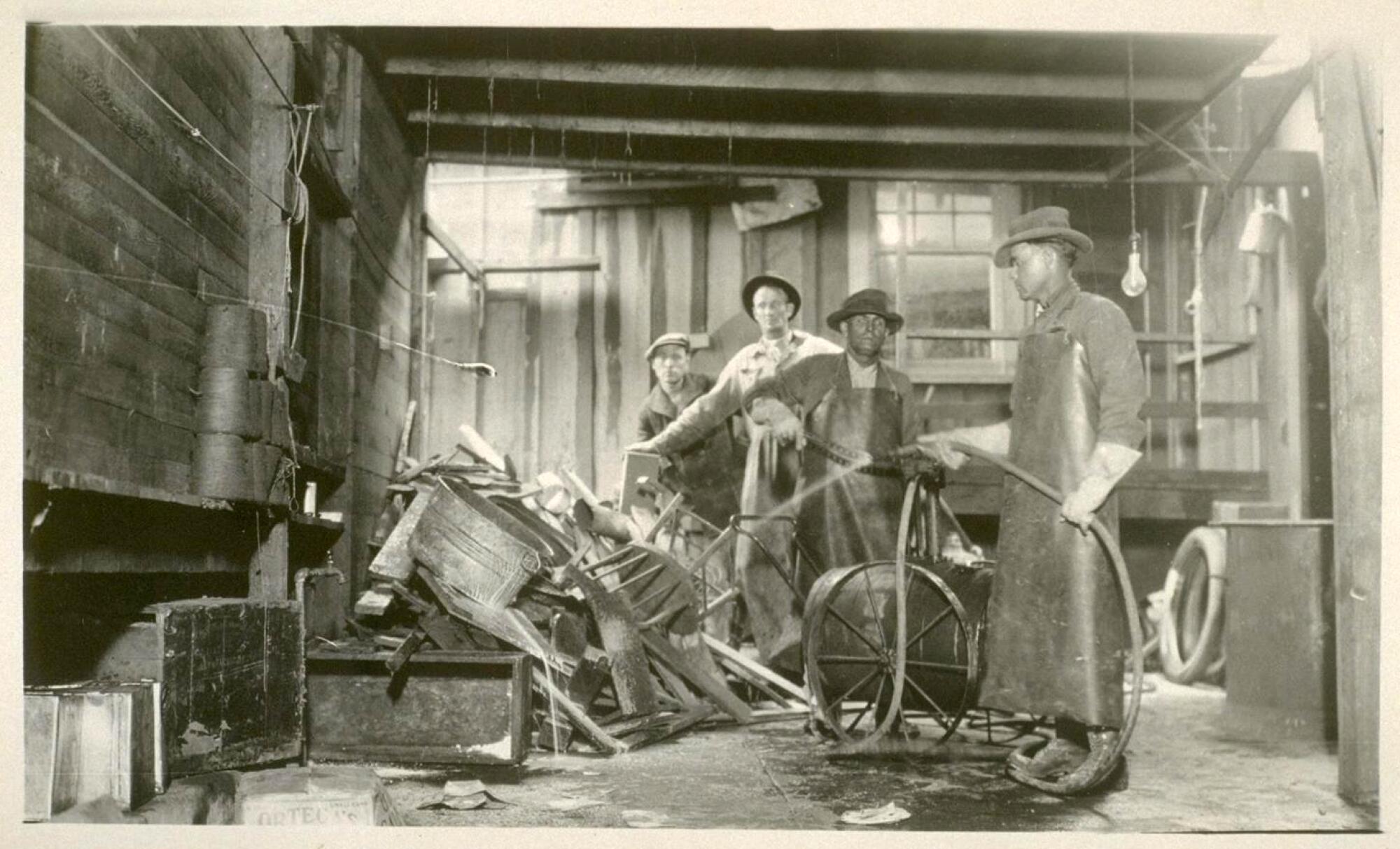

For many Mexican laborers who settled in Los Angeles in the early 1900s, the weight of this segregation pressed them and their families into areas east of downtown, on the banks of the L.A. River. There, homes were known as “house courts” — groupings of wooden shacks and sheds, often with four or five people per room. The worst had no windows and reeked of raw sewage.

It was then that L.A.’s leaders first learned of the catastrophes that could erupt in such cramped conditions. House courts became incubators for tuberculosis, which is transmitted through the air like COVID-19. Even at the time, political and public health officials knew that overcrowded housing contributed to the spread of the disease.

But they didn’t blame the housing conditions, the low pay or the segregationist laws for the outbreaks. Instead, they blamed race.

L.A.’s public health director asserted in 1916 that Mexicans had “little to no knowledge of sanitation and tend to bad housing, overcrowding and conceal contagious diseases.” A U.S. government surgeon blamed high tuberculosis rates among the Mexican population on “an extremely low racial immunity.” Many homes were razed or burned down under the banner of public health.

As business boomed, immigrants kept coming. By the end of the 1920s, about a quarter-million Angelenos were of Mexican descent.

Then the Great Depression ground the economy to a halt, and civic leaders decided it was time for Mexicans to “go home.” They seized on the disease to spark a panic. Although tuberculosis cases in Mexican neighborhoods had long been double those of the rest of the city, the issue suddenly became a crisis.

In his 1930 annual address, Mayor John C. Porter called Mexican residents “a menace to the community at large.”

What followed was one of the largest mass expulsion events in American history. In the so-called “repatriation” campaign carried out by L.A. County and city authorities, tens of thousands of Mexicans and their American-born children were loaded onto trains with one-way tickets paid for by the county and dispatched south across the border.

Emilia Castañeda, born in L.A., was sent with her father and older brother to her father’s home state of Durango, Mexico, in 1935. Castañeda’s mother, a domestic worker, had died of tuberculosis the year prior; a campaign against foreign labor put her father, a stonemason, out of work.

“The county cooked up the scheme to get rid of people,” said Christine Valenciana, Castañeda’s daughter. “ ‘Let’s get rid of them; let’s offer them a one-way train ticket, and who gives a damn whether they’re citizens or not.’ ”

Castañeda, derisively called “repatriada” by relatives and classmates in Mexico, dropped out of school and started working. After her godmother sent her a copy of her birth certificate, Castañeda returned home in 1944 at age 18.

When World War II ended, L.A. faced the worst housing crisis in its history. Tens of thousands of veterans came to the region and brought their families with them. They squatted in tents, trailers and houseboats and doubled or tripled up in whatever living spaces they could find.

In response, local reformers embraced the idea of new publicly owned homes, boasting that soon Los Angeles would become “the nation’s first city free of bad housing.” Backers called “a decent home an American right.”

The grand realization of this grand vision would be Elysian Park Heights, designed by famous modern architects to include two dozen 13-story towers, 163 two-story buildings, churches, schools, nurseries, a commercial center and a community hall amid steep hills in the heart of Los Angeles. It would be a new neighborhood for 17,000 people, one of the nation’s largest public housing developments and a striking alternative to the dominant mode of growth that had thus far defined Los Angeles.

The “city of homes” contemplated by the designers of Elysian Park Heights was to feature density and diversity — the project would be racially integrated “for the survival of our democracy,” supporters maintained — rather than sprawl and segregation.

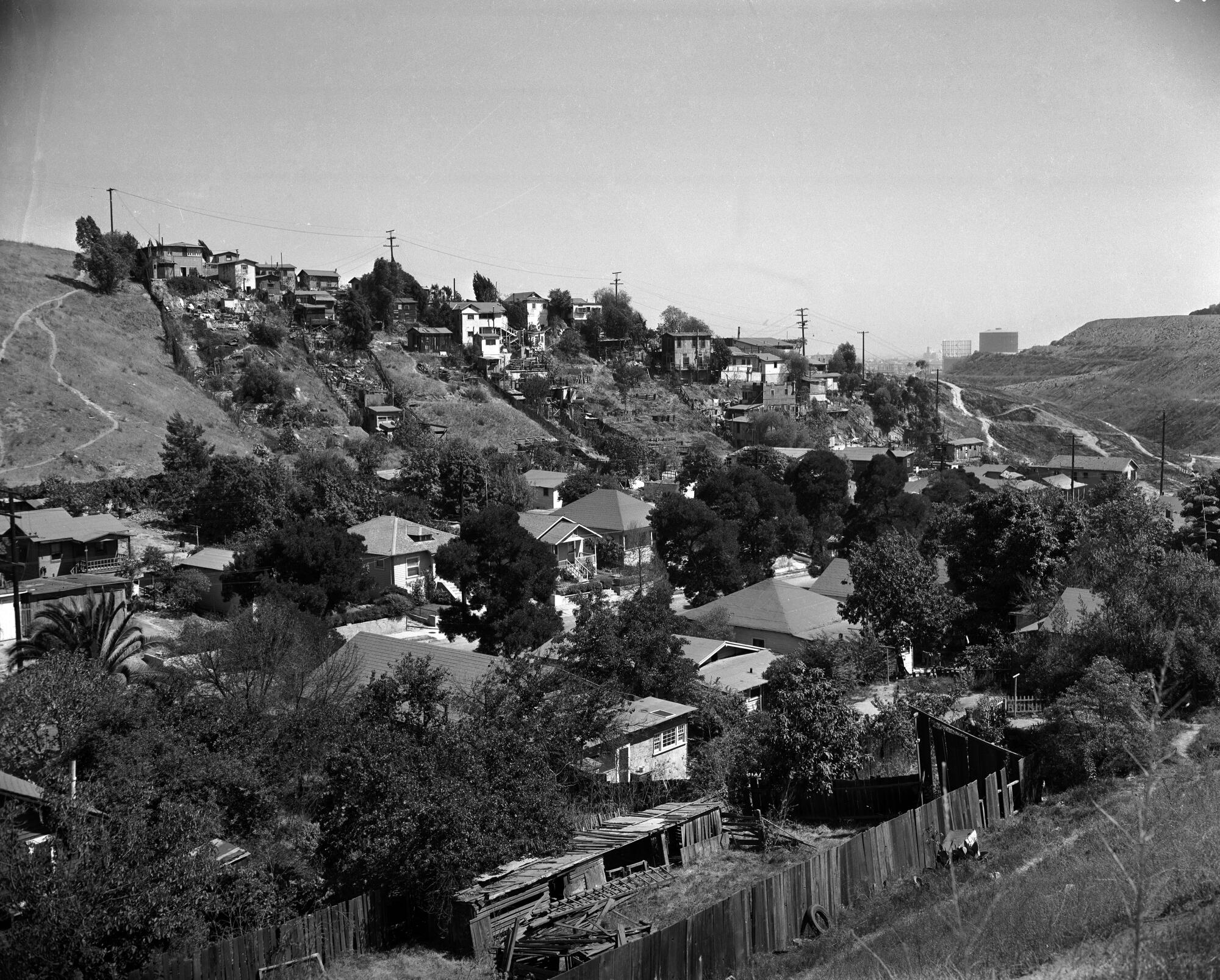

But some 4,000 residents, mostly Mexican, already lived in old wooden houses, trailers and white cottage bungalows alongside chicken coops and vegetable gardens on the site of the proposed housing project. Families in the neighborhoods collectively known as Chavez Ravine were promised new homes in Elysian Park Heights, but many didn’t understand why they had to leave.

As a child, Carol Jacques’ favorite part of the day was her trip home from school along the dusty roads of Palo Verde, the part of the community where she resided.

Mothers standing at their doorsteps would offer Jacques a taste of the stews they’d cooked the night before. Sometimes, she’d walk away with newborn canaries — and, once, a puppy — when neighbors’ pets had babies. Around holidays, she’d watch women cut bouquets of bright chrysanthemums to adorn the Catholic church.

“The little walk up the hill was everything,” said Jacques, who was 8 in 1951, when her family was forced to sell their three-bedroom home to the city.

Jacques’ grandfather, Lorenzo Ayala, had built the house himself nearly three decades prior, after emigrating from Mexico, setting up a horse-drawn cart to sell produce and renting a home nearby. Ayala had also saved enough to buy the land next door, where he grew corn and squash and raised chickens and goats.

As one of the few places Mexican families were able to own homes at the time — Chavez Ravine’s homeownership rate actually exceeded the city’s — the area had been largely ignored by L.A. civic officials until they needed a spot for their showcase project. Its location, size and sparse and haphazard development made it an easy target; so did the working-class Mexican residents’ lack of political power.

Jacques remembers when city officials handed an eviction notice to her aunt. Their neighbors soon received the same knock on the door.

“There was a lot of breaking into tears and ‘What are we going to do, and where are we going to go? This is our house, our land, our tierra,’ ” Jacques said. “Oh, God. I get chills when I think about it. It was a terrible time.”

Jacques and many others went to nearby neighborhoods, where their families were able to buy small homes with what little money they received from the city.

But the monumental new affordable housing community that had been promised — and that created such anguish — would never happen.

Real estate interests, believing that public housing risked their profits and L.A.’s way of life, responded with ferocity during what was the height of McCarthyism.

They financed opposition groups that warned in leaflets that “public housing would be the last rung in the ladder toward complete socialism, one step this side of Communism and Our downfall.” They sponsored an amendment to the state Constitution to effectively block public housing projects. They sicced federal and state Un-American Activities committees on the architect of the city’s plan, who was fired as housing director after accusations that he was a communist. And, to seal their victory, they handpicked a candidate to defeat the pro-public-housing mayor.

In 1953, less than four years after they were announced, Elysian Park Heights and L.A.’s public housing plans were dashed.

The decision left Chavez Ravine a ghost town. Dwindling holdouts remained scattered throughout the hills, while the new civic promise was to turn the area into public parkland.

That promise also didn’t last long. City leaders courted Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley to come West, taking him on a helicopter ride to showcase Chavez Ravine’s potential. O’Malley was sold while still in the air, and the city gave him the land to build Dodger Stadium.

In 1959, on the eve of the stadium’s groundbreaking, two squads of sheriff’s deputies violently evicted the Aréchiga family, some of Chavez Ravine’s final residents, from their home. They dragged Aurora, a mother of two and a war widow, down the stairs and pulled out six others. Less than 10 minutes later, the city bulldozed the home while the family watched.

Chavez Ravine’s destruction cemented the region’s path toward private subdivisions as its primary means of growth. But the community’s annihilation wasn’t isolated.

Civic leaders similarly dubbed other Mexican and nonwhite neighborhoods blighted slums, then cleared those homes for freeway and urban renewal projects. Freeway construction in Boyle Heights, including the 135-acre East Los Angeles interchange, pushed out at least 10,000 people in what was a multiethnic community.

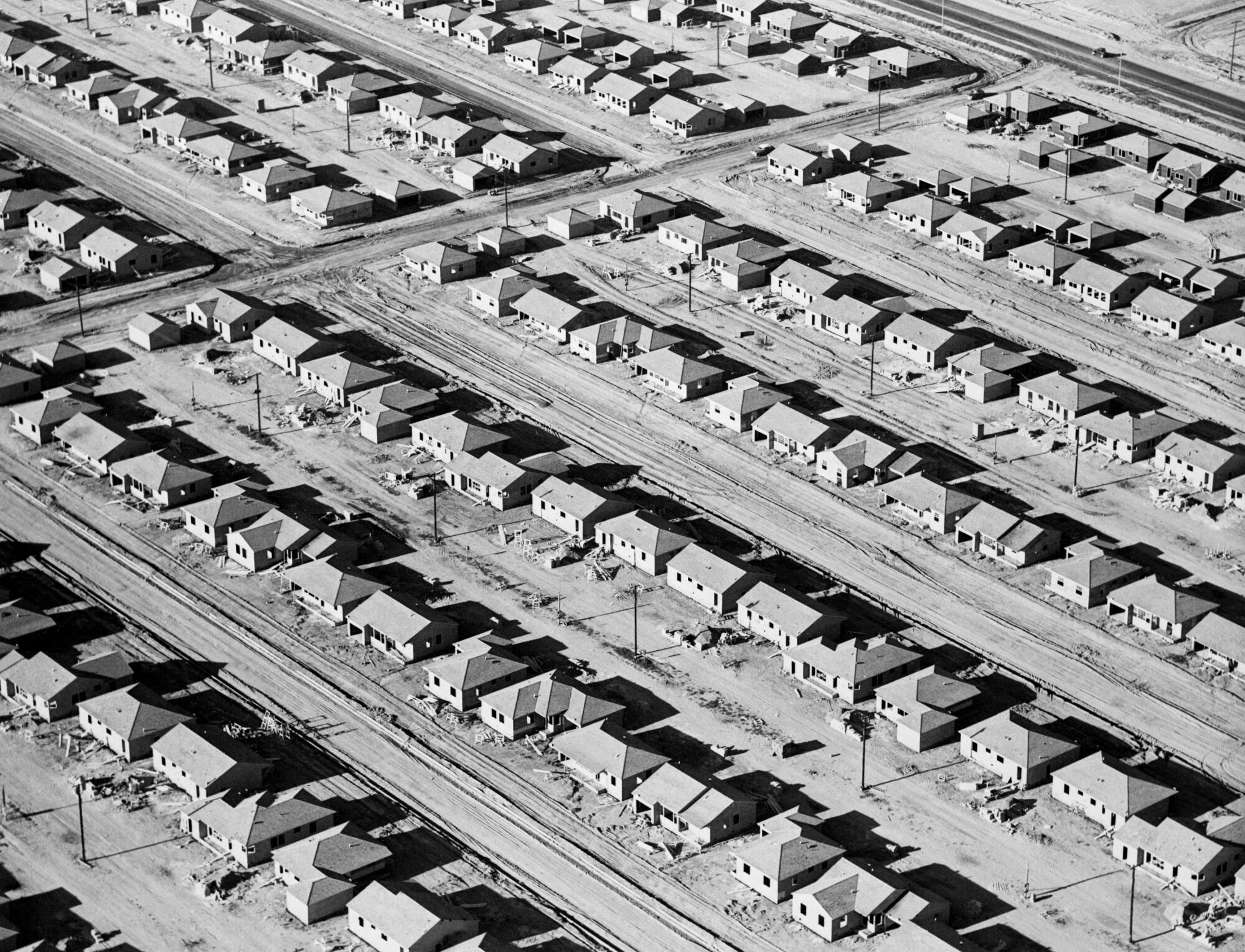

During this time, L.A.’s population boom churned on, spurring waves of home-building to accommodate the still-arriving masses. More than a million houses were built in the county during the 1950s and ’60s.

Developers chewed up walnut and citrus orchards in the San Fernando Valley for thousands of tract homes. In just over three years, lima bean fields near Long Beach became 17,500 houses in a community called Lakewood, built at the rate of a new home every 7½ minutes before completion in 1953.

Unlike Elysian Park Heights, these new cities of homes hewed to L.A.’s original, racialized promise of plenty.

The combination of restrictive covenants, federally subsidized mortgages for white families and real estate interests steering away prospective Asian, Black and Latino homeowners left many communities essentially white only. In 1960, more than 99% of Lakewood’s residents were white.

The residential construction boom, however, wasn’t only about suburbanization. To meet some of the demand, thousands of low-rise “dingbat” apartments with parking underneath were springing up in L.A.’s established neighborhoods, offering more affordable rents.

By the late 1960s, that growth sparked its own backlash. Court rulings and new laws governing fair housing forced neighborhoods that had blocked nonwhite residents to integrate. Largely white homeowner groups feared that the social unrest that had exploded in 1965 in the Black community of Watts would come to their area.

Their interests aligned with a nascent environmental movement. They agreed that all the new development in recent decades had made the city polluted and overpopulated. The city began declaring many neighborhoods, particularly on the Westside, off limits to more housing.

In the mid-1960s, L.A.’s zoning code would allow enough new homes to accommodate a population of 10 million. But over the next two decades, changes made through sweeping ballot measures and technical bureaucratic ordinances reduced that figure to 4 million.

City leaders believed that their actions would keep more people from coming to Los Angeles, said Greg Morrow, a professor of real estate at UC Berkeley who has written about the city’s “slow growth” movement. Had the old zoning rules persisted, many communities probably would have seen bungalows torn down and replaced with small apartments. Doing so would have simultaneously lowered the cost of rentals and made room for a larger population, he said.

Instead, when impoverished newcomers — buoyed by relaxed immigration laws and the region’s endless demand for cheap labor — began arriving from Mexico and Central America in the 1970s, they simply settled where they could, usually in older neighborhoods near rendering plants, freeways, oil derricks and factories: places like Pico-Union.

In 1970, L.A. wasn’t among the 10 large counties nationwide with the most crowded housing, according to a Times analysis of census data. In 1980, it soared to No. 3 on the list, then, in 1990, to No. 1, where it has remained ever since.

The result of all the decisions, Morrow said, was a region that was both overcrowded and undercrowded at the same time.

“We put in place a process that favored those who own homes, and they didn’t want their neighborhoods to change,” he said. “The dynamic that plays out is you end up with areas that are very, very affluent and walled off from the rest of us. And areas that are the Wild West.”

Although conditions for overcrowding were decades in the making, starting in the 1970s, it seemed to happen all at once.

Apartments housed so many families that children had to sleep in shifts. Fifth- and sixth-graders in Westlake, a neighborhood on Pico-Union’s northeast border, had their school days shortened because classrooms were overflowing.

A 1987 Times investigation revealed that about 42,000 garages were sheltering approximately 200,000 people in L.A. County alone. And by 2000, at its peak, overcrowding in L.A. was four times the national rate, according to a Times analysis of census data.

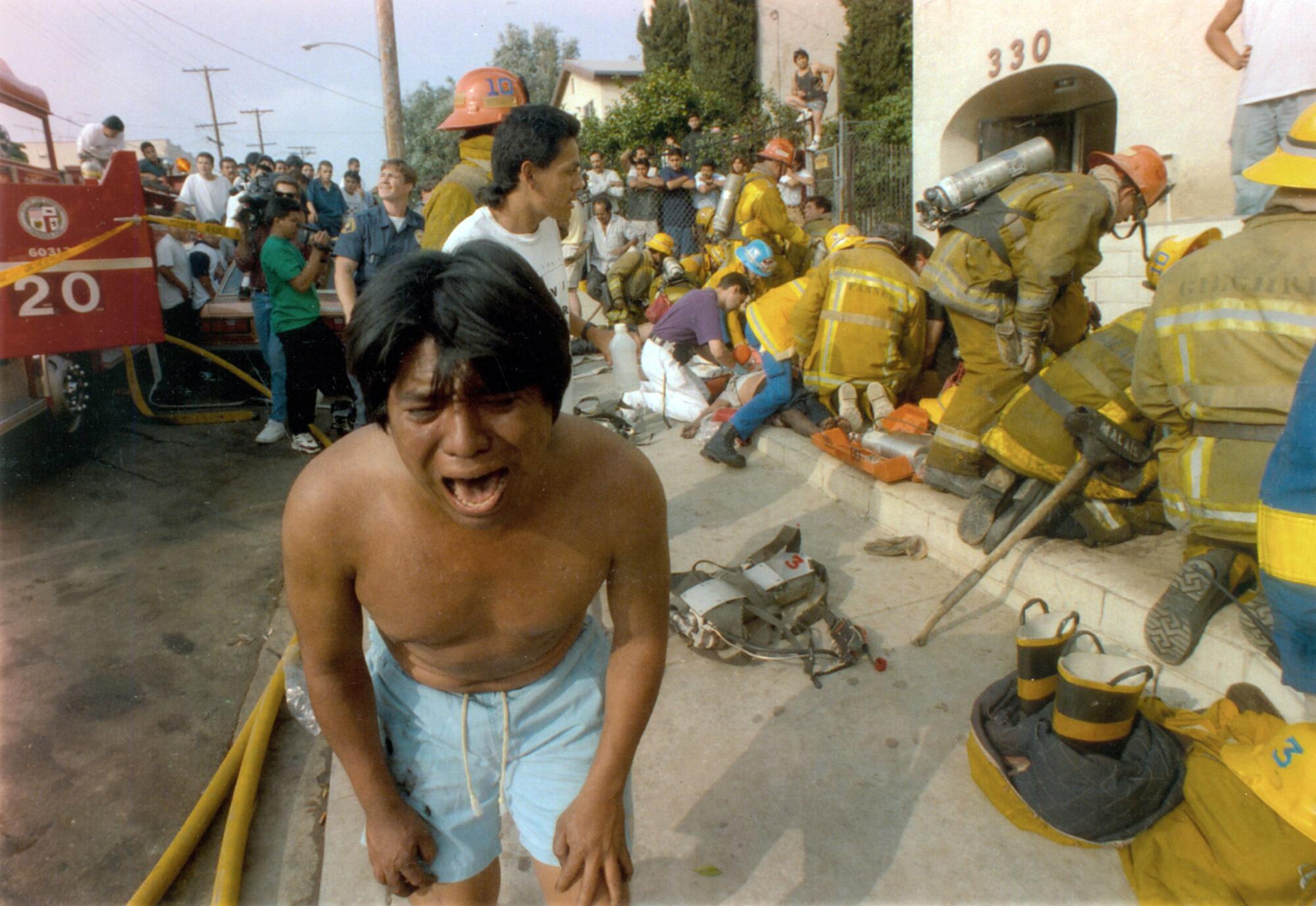

Families burned or choked to death in house fires. After 10 people perished in a blaze in a packed Westlake apartment building in the mid-’90s, Cardinal Roger Mahony eulogized the victims and pleaded for more humane living conditions.

“If, in fact, their lives serve to provide protection to others, then their martyrdoms will not have been in vain,” Mahony told mourners at the funeral.

These tragedies and appalling conditions, combined with the speed of L.A.’s demographic change, brought overcrowding from the shadows into public view. Within 20 years of the arrival of large numbers of Mexican and Central American immigrants in the 1970s, the percentage of L.A. residents born outside the U.S. nearly tripled.

As this was happening, density became even more of a dirty word in the city. Mayor Eric Garcetti recalled that the prevailing wisdom among elected officials was that neighborhoods needed to be protected from growth. Supporting development in established areas, he said, was “seen as political suicide.”

“A tactical defense of neighborhoods became a strategic disaster for the city,” Garcetti said.

Overcrowding radiated from the city throughout Southern California as communities responded mainly by attempting to push the masses elsewhere. Rather than promote affordable housing construction, local governments tried to prohibit apartments from getting built, crack down on unpermitted ones or limit the number of people who could legally live in a home.

Although these efforts were nominally concerned with the health of those living in overcrowded homes or with broader quality of life, debates burned brightest in areas of Los Angeles and Orange counties that had declining white populations and growing Latino ones.

In Santa Ana, Ascención Briceño’s family found itself at the center of the fight.

The family shared a cramped one-bedroom apartment, where three children slept on bunk beds, and Briceño and his wife on the living room sofa. They lived in 395 square feet, along with cockroaches and rats.

It was the late 1980s, and many neighbors in their apartment building on Minnie Street were also wedged into small apartments. When they tried to get repairs for their units, they were told they’d be evicted for having too many people living there.

City Council members also believed there were too many people living in the apartments and others across Santa Ana. They passed rules that would allow no more than four people in apartments like Briceño’s. The family, and thousands of others, faced eviction.

Santa Ana leaders argued that their actions were necessary for safety. But during council meetings, protesters were shouted down with chants of “Go back to Mexico!”

Briceño, who had arrived from the Mexican state of Jalisco two decades before, said the city’s restrictions were an attempt to force Latinos from Santa Ana. He sued.

“Santa Ana was becoming more and more Latino, and yet the leadership was predominantly more middle class, more affluent and, in many cases, more white,” Briceño’s son Gerardo said in a recent interview. “They didn’t quite understand why these apartments were overcrowded, or felt the need to criticize or comment. I think their experience was so different than ours.”

An appeals court threw out Santa Ana’s law. Judges understood that overcrowding was taxing city services, but the alternative, they said, was a “parade of horrors”: More families would become homeless, and communities without strict occupancy limits would become even more crowded than they already were.

Other cities’ efforts also met fierce resistance. Bell Gardens, a southeast L.A. suburb, had by 1990 turned from a haven for working-class white families into one of the country’s poorest and most crowded communities, with nearly nine times as many Latinos as white people.

The all-white City Council proposed demolishing broad swaths of the city’s apartment-heavy housing stock and replacing them with single-family homes and open space. Latino residents revolted, denouncing the plan as “Mexican removal.”

“[The people here] have crossed rivers, they have crawled under fences to get here,” one resident said at a council meeting. “They have a dream, and they are not going to let you take it away from them.”

Activists recalled councilmembers supportive of the rezoning, and soon the council became majority Latino. Today, the overcrowding rate in both Bell Gardens and Santa Ana still stands at around 30%.

By the time overcrowding was considered a crisis, potential solutions, such as widely increasing the availability of low-income housing, had become expensive and would take time to work, said Gary Blasi, a law professor emeritus at UCLA. City politicians have never made lasting efforts to address the mismatch between a shortage of housing and a surplus of poor people, he said.

“The acceptance [of overcrowding] was across the board,” said Blasi, who was involved in L.A. city campaigns in the 1990s to address poor housing conditions, “from people who just didn’t care to people who cared but didn’t have a solution that didn’t involve massive infusions of resources that were never going to come.”

As immigration waned after 2000, so did overcrowding in L.A. But its percentage of homes that are overcrowded remains the nation’s highest.

Today, many higher-income areas are still protected from most new development. Housing specifically set aside for low-income residents remains in short supply. Median incomes for Latino families in the county, at $60,000, remain 35% lower than those for white households, per census data.

Still, many immigrants who arrived in the ’70s and ’80s were able to save enough money to move into the middle class and buy homes, said William Fulton, author of “The Reluctant Metropolis: The Politics of Urban Growth in Los Angeles.”

The Briceño family was among them, purchasing a house in Santa Ana in the mid-1990s. Paying cheaper rent for a crowded apartment helped them, like others, to eventually improve their living situation.

But Fulton can’t imagine families being able to do that today.

“I don’t even know if it’s possible to overcrowd your way into buying a house anywhere in L.A. when every house is $1 million,” Fulton said.

Magdalena Garcia has lived in overcrowded housing in Pico-Union for four decades. She grew up sharing a studio with her parents. Now, she’s in a one-bedroom with her husband and six children, unable to afford more than the $900 they pay in rent.

Today, more than three-quarters of Pico-Union’s residents are Latino, and the median household income is $38,294 — half that of L.A. County as a whole.

As a result, families, friends and strangers jam into the neighborhood’s old Victorian homes, which have been converted into warrens of studio and one-bedroom apartments. Furniture stores stock up on sofa beds, twin-size mattresses and bunk beds that can fit in compact spaces. Signs scrawled in Spanish are taped around utility poles: “Renting space in the living room to a person with a stable job (with rules),” “Renting a small room for an older person.”

In Garcia’s home, eight family members share the bedroom, split among bunk beds and a full bed. Shelves burst with towels, clothes and blankets. Boxes are stacked in the living room.

During the day, Garcia’s son Jesse Iran Davila Garcia studies at the table. But when his younger siblings trickle in, the 19-year-old pulls a chair to an alcove outside the apartment door — “his office.” It’s where he studied throughout high school, the only place he could concentrate.

Lack of space to concentrate on schoolwork is something Garcia’s children have wrestled with all their lives. Studies have found that living in crowded homes as a child can serve as “an engine of cumulative inequality” throughout life.

On a recent Thursday, Jesse put his textbook on his lap, preparing for a three-hour exam for his real estate license.

“My dream is to someday buy a home for my family,” he said.

In May, COVID tore through the family’s apartment. With no way to isolate from one another, the family members tested positive one by one. All recovered.

With the pandemic battering the health and incomes of poor Latino workers and the continued rise in housing costs, many worry that overcrowding is going to worsen — along with its twin scourge, homelessness.

An estimated 650,000 families in the L.A. area are behind on their rent, according to a recent U.S. Census Bureau survey, and problems paying for housing have forced some into living situations even more crowded than before.

Last year, in Echo Park, Elvira had no choice but to welcome her son, his girlfriend and their children into the one-bedroom apartment already shared by seven people. Her son had lost his job in hotel housekeeping because of the pandemic and needed to save money.

“I have to make this sacrifice to help my children,” said Elvira, who asked that her last name not be used for fear of retaliation from her landlord. “If I don’t help them, who will?”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

L.A.’s hard realities do not spare those who’ve lost friends and family members to the pandemic.

In Pico-Union, Gregorio Soc-Lux shared a one-bedroom apartment with three other men from the same town in Guatemala. They split the $1,622 monthly rent and slept in bunk beds. Soc-Lux would walk the three minutes to his job at Dino’s Famous Chicken.

The men had lived together since 2007.

“You can’t do it alone,” Soc-Lux’s roommate Jose Aguilar said. “There’s no other choice.”

In the winter of 2020, Soc-Lux developed a fever and a cough, and two of the other roommates grew seriously ill. On Dec. 8, 52-year-old Soc-Lux died in the living room.

His roommates grieved, then went about finding another man to take his place. Rent was due.

About this story

To compensate for changes in the census questions, the overcrowding rate over time was analyzed by county as an index to the national rate.

Data on COVID-19 cases and deaths come from the Los Angeles Department of Public Health. Communities with fewer than 5,000 residents are not included in the charts. Death rates are adjusted for age distribution in the underlying population. Data are current as of Oct. 1.

This series is reported and written by Brittny Mejia and Liam Dillon, with data reporting by Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee and Sandhya Kambhampati. Additional data reporting by Ryan Menezes. Photography by Gary Coronado, with photo editing by Marc Martin. The editors are Joe Mozingo, Hector Becerra, Shelby Grad and Scott Kraft. Graphics editing by Sean Greene and Hanna Sender. Library research by Cary Schneider and Scott Wilson. Engagement editing by Mary Kate Metivier and Javier Panzar. Story design by Allison Hong and art direction by Martina Ibáñez-Baldor. Copy editing by Carolyn Horwitz and Minh Dang. Additional digital help from Lora Victorio and Beto Alvarez.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.