Kevin McCarthy will retire from Congress at end of year

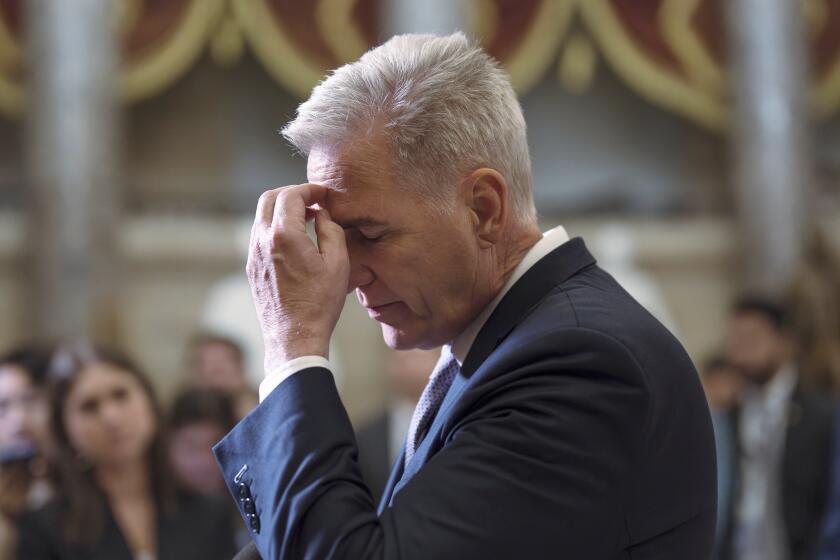

Former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy will not seek another term in Congress, ending a tumultuous two-decade career in public office that was marked by a swift ascent and descent in Washington GOP leadership. He said he would leave the House by the end of the year.

U.S. Rep. Kevin McCarthy’s departure provides a rare opportunity for an ambitious California Republican to seek higher office.

McCarthy announced his decision days before the state’s deadline to file to run again for his Bakersfield-based seat — and just nine weeks after bitter infighting among House Republicans led to his historic Oct. 3 ouster from the leadership post. His departure opens the door for what could become a contested House race in California’s heavily Republican Central Valley.

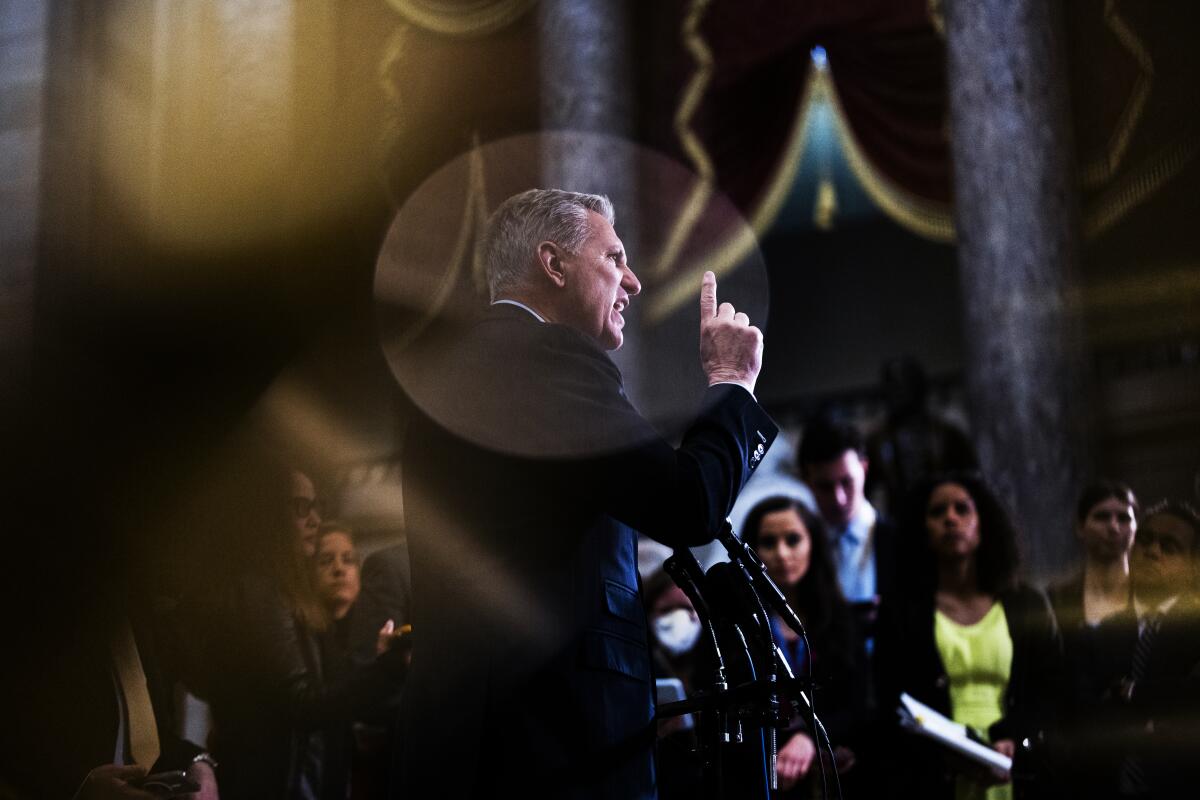

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, McCarthy lauded his record: serving as his party’s whip, majority leader and speaker and diversifying the House GOP conference. “It is in this spirit that I have decided to depart the House at the end of this year to serve America in new ways,” he wrote. “I know my work is only getting started.”

“My story is the story of America. For me, every moment came with a great deal of devotion and responsibility,” McCarthy said in a video announcement. “Giving my best to all of you has been my greatest honor.”

McCarthy’s retirement from Congress continues the steep decline of California’s political power in Washington, where just a handful of lawmakers from the state remain in leadership posts. The delegation lost decades of experience and seniority with Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s death in September. San Francisco’s Rep. Nancy Pelosi stepped down from the House’s Democratic leadership in January. Only two Californians remain in leadership positions: Reps. Pete Aguilar of Redlands, chair of the Democratic Caucus; and Ted Lieu of Torrance, the Democrats’ vice chair.

Hard-line Republicans joined with Democrats to remove the Bakersfield Republican from the speaker’s chair.

McCarthy’s retirement is also a blow to GOP fundraising efforts. Last election cycle, he helped raise hundreds of millions of dollars for Republican campaigns. On Wednesday, some lawmakers lauded McCarthy’s tenure. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, once McCarthy’s Republican counterpart in the upper chamber, said the Californian’s constituents “were fortunate to have such an optimistic doer represent them for 17 years.”

“I am proud of the work we accomplished together in the Capitol, and I wish him the very best as he writes a new chapter,” McConnell added on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter.

Not all of McCarthy’s colleagues are sad to see him go. Florida Republican Matt Gaetz was leader of the eight hard-right lawmakers who forced McCarthy out as speaker with the help of Democratic votes. The group had griped that McCarthy worked too closely with Democrats to suspend the nation’s debt ceiling and avert a government shutdown.

Congress has voted to prevent a government shutdown. But House Speaker Kevin McCarthy had to rely on Democrats to get the bill to President Biden’s desk.

McCarthy’s reliance on bipartisanship to advance legislation near the end of his career stands in contrast to the partisanship he demonstrated when he first came to Washington in 2007.

The Californian was elected to his House seat in 2006, and quickly climbed the ranks of his party’s leadership after demonstrating his fundraising prowess. His first bid for the speakership, in 2015, collapsed in part because more-conservative tea party Republicans withheld their support.

After he courted the far right and became an ardent backer of then-President Trump ahead of the 2018 midterm election, McCarthy was elected leader of the House’s GOP minority.

But even after Republicans reclaimed the House in the 2022 midterm election, McCarthy struggled to secure the speakership, the chamber’s top post. In January, he needed 15 tries to win enough votes from his party to clinch the speaker’s gavel. In exchange for their votes, he agreed to make it easier for any lawmaker to call for a vote on removing him.

As speaker, McCarthy scored few victories for his party. He opened an impeachment inquiry against President Biden at the behest of far-right Republicans, but he never wielded the power that past speakers such as Pelosi had. He was unable to rally his steeply divided conference on an array of issues, forcing him to rely on Democrats’ votes to suspend the nation’s debt ceiling in May and avert a government shutdown in September.

It was these moves that enraged Gaetz and other GOP rebels. Once ousted, McCarthy declined to run for speaker again, and the party finally settled on Louisiana Rep. Mike Johnson after weeks of infighting.

Johnson has also struggled to unify the Republican caucus — he relied on Democratic votes to avert a government shutdown in mid-November — but GOP hard-liners have so far mostly spared him their wrath.

New House Speaker Mike Johnson just relied on Democratic votes to fund the government. Will it come back to haunt him?

The GOP’s October civil war took a toll on the party, though, with the infighting repeatedly spilling over in public. Last month, a Tennessee Republican who had voted to oust McCarthy accused the former speaker of elbowing him in a Capitol Hill hallway. (McCarthy denied the accusation, but a reporter present at the exchange backed the Tennessean’s account.)

The internal tumult also prompted some high-profile departures.

Rep. Patrick T. McHenry (R-N.C.), a close McCarthy ally who served as interim speaker after the Californian’s ouster, said Tuesday he would leave at the end of his term. Like McCarthy, McHenry was among a new generation of ambitious House conservatives who sought to lead the Republican Party in the last decade.

Also like McCarthy, former GOP House Majority Leader Eric Cantor of Virginia and former House Speaker Paul D. Ryan of Wisconsin eventually saw themselves outmatched by the rambunctious far-right of the GOP, which rejects almost any deal making with Democrats.

McCarthy’s retirement “is another sign that [President] Trump has dramatically changed the GOP and its possible leaders,” Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond School of Law, told The Times in an email. Tobias surmised McCarthy is leaving Washington “because he has a better offer of more rewarding challenges than fighting the political wars that are consuming the House and the nation.”

McCarthy’s departure will also further narrow the GOP’s majority.

The House expelled New York Republican George Santos last week, and a special election to fill his seat won’t be held until February. The combination of Santos’ expulsion and McCarthy’s departure at the end of this year will leave Republicans with just a three-seat majority in the chamber, making it even more challenging for Johnson to lead his fractured conference.

House Republicans will need to work with the Democratic-controlled Senate and President Biden again next month if they hope to avert a government shutdown.

“I can assure you Republican voters didn’t give us the majority to crash the ship,” Georgia GOP Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene wrote on X, shortly after McCarthy announced his departure. “Hopefully no one dies.”

Gaetz, who orchestrated McCarthy’s ouster, on Wednesday knocked the Californian for not finishing his term and leaving the GOP with an even slimmer majority. For all of Pelosi’s “flaws,” Gaetz said, she stayed in Congress after leaving the speaker’s chair, abiding by a 2018 agreement to make way for the next generation of leaders.

McCarthy’s retirement “is not an act of patriotism or moving on to the next fight,” Gaetz said. “It is an act of abject selfishness and it is revealing that if Kevin McCarthy can’t swing the gavel and be in charge and make the decisions, that he’s not willing to be a team player.”

A special election, scheduled by Gov. Gavin Newsom, to fill McCarthy’s seat is expected next year. Two prominent Republicans who could jump into this race include state Sen. Shannon Grove and Assemblymember Vince Fong.

Newsom spokeswoman Erin Mellon told The Times the governor has not yet set a date.

Why do a soul-crushing job with a 3,000-mile commute when you could do something else? Californians who’ve left Congress say they don’t miss it at all.

Get our Essential Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.