Appreciation: Jim Murray has been gone 25 years. There will never be anyone else like him

Wednesday is a reminder of a day that will live in infamy in the sports department of the Los Angeles Times. Make that the entire city. It was on Aug. 16, 1998, that Jim Murray died. That’s an unthinkable 25 years ago.

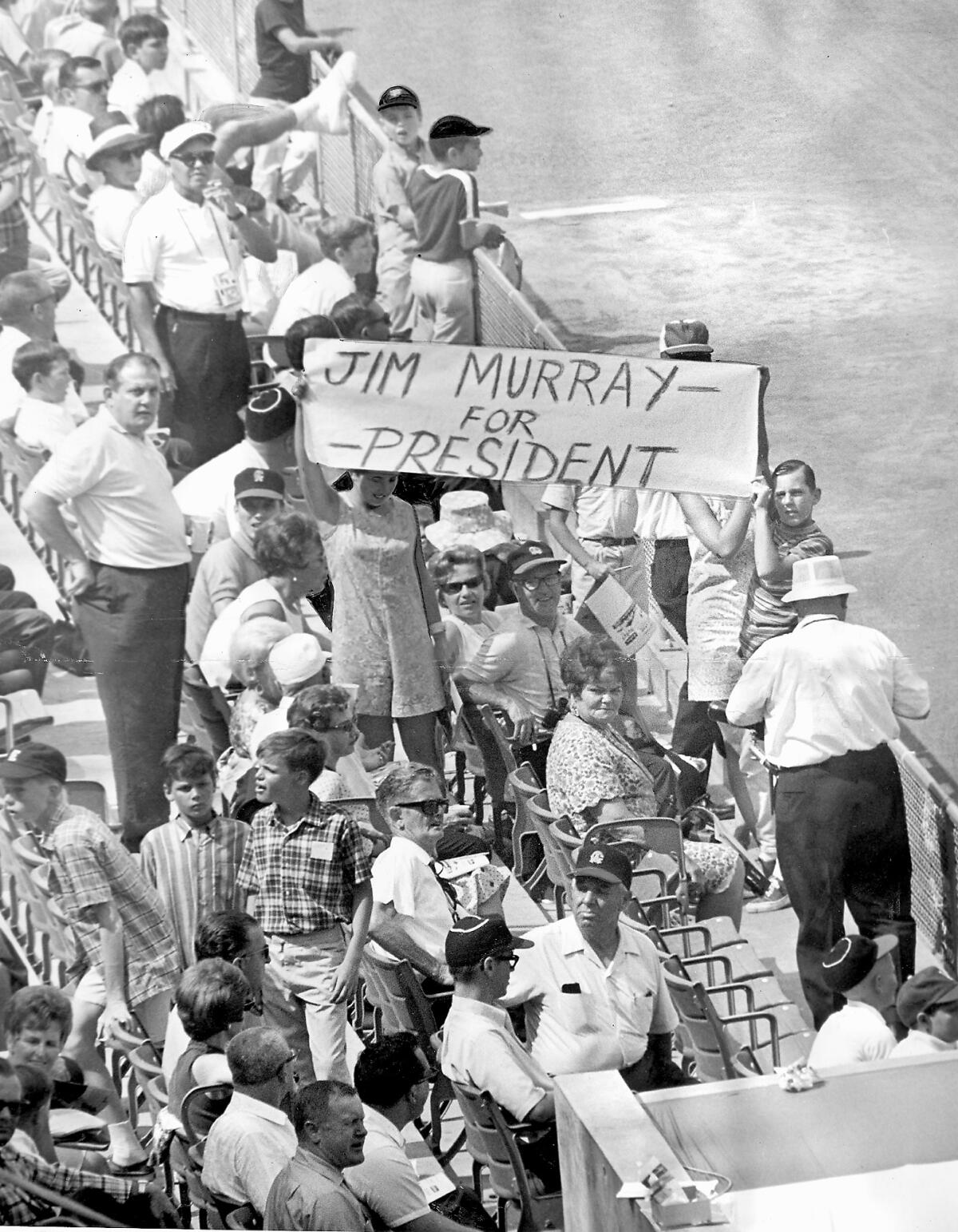

There was never anybody like Murray. Never will be. He was part sports columnist, part Don Rickles and part Socrates. He wrote for The Times for 37 years and won his Pulitzer for commentary in his 30th year. The general reaction to that, at the paper, and around Los Angeles, was: What took the Pulitzer people so long? The problem was, sports writers didn’t win Pulitzers except if they worked for the New York Times. Still don’t. Only a writer the caliber of Murray could break the East Coast stranglehold. Now, the New York Times doesn’t even have a sports section. Ponder that, Pulitzer people.

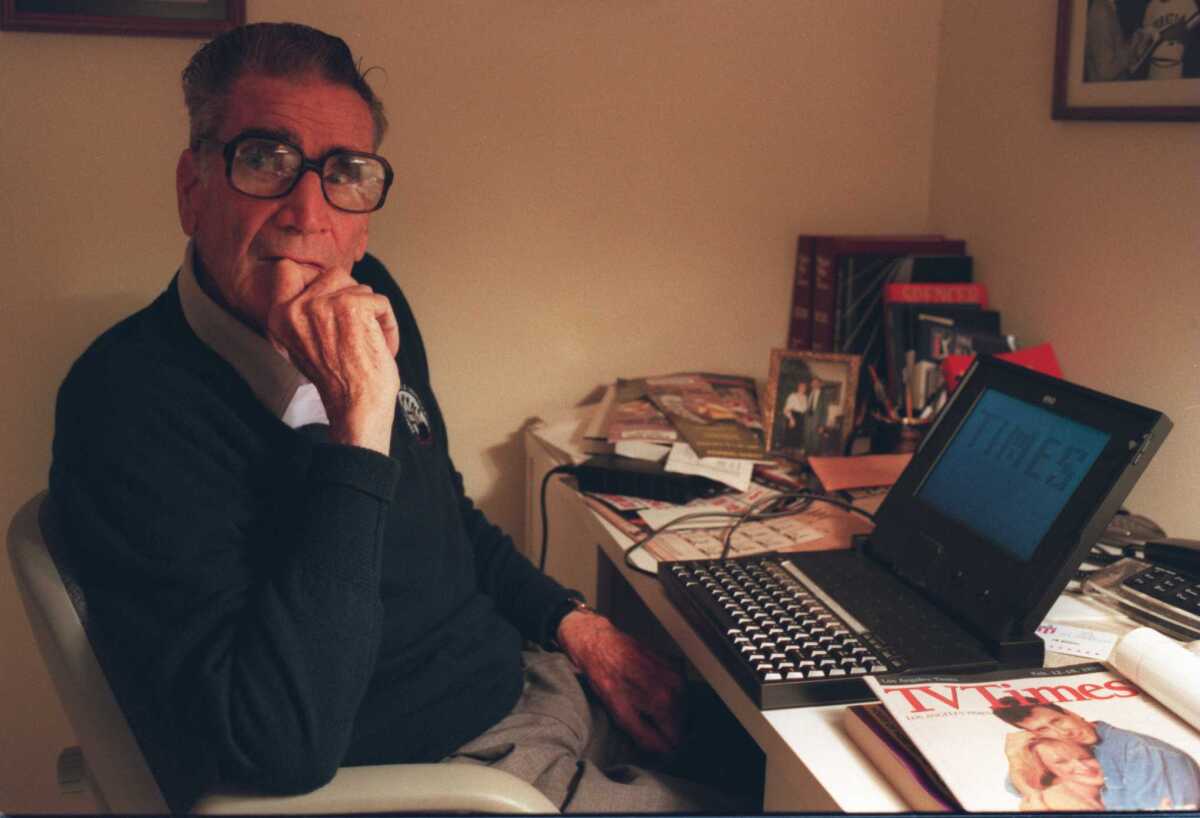

Murray was 78 when he died, and in poor health. He went for a while without being able to see because he had a detached retina. That forced him to sleep at night with sandbags stabilizing his head. People with detached retinas are cautioned against quick movements of their head. For a while, he walked around with a pig valve in his heart. Yet, when he sat down in front of a keyboard, he was the Mighty Atlas.

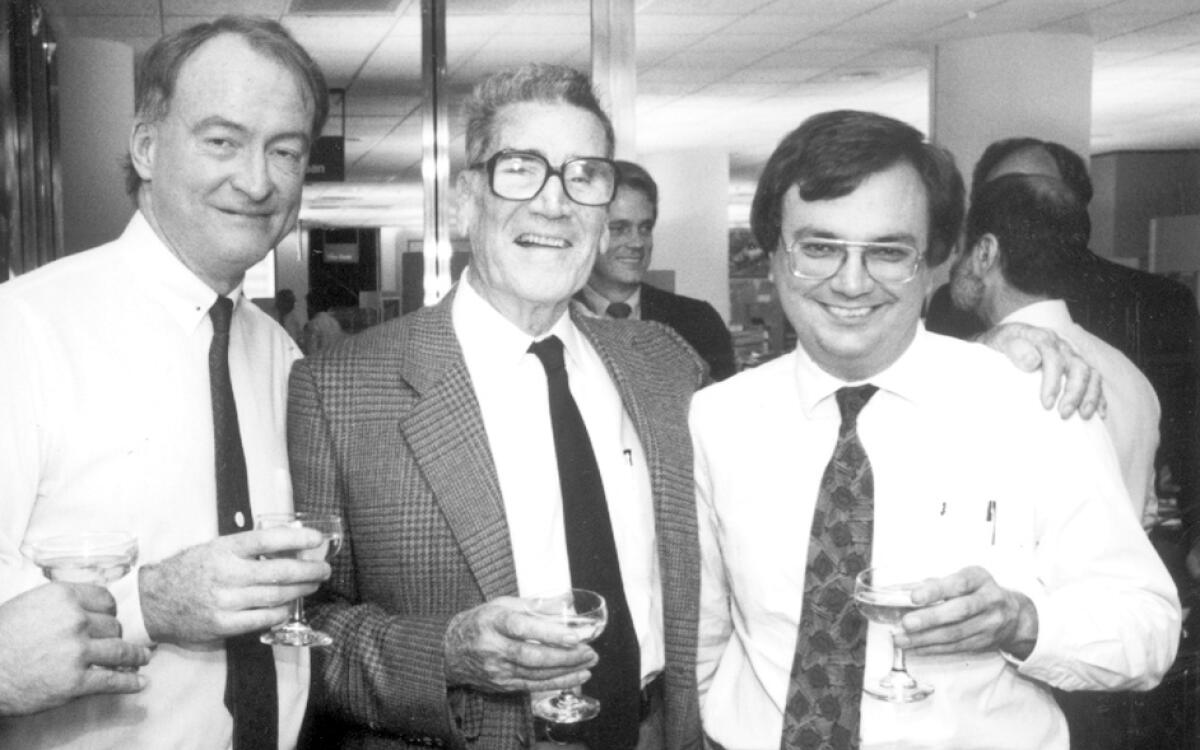

Mike Downey, a much-decorated and respected columnist at The Times, wrote to Murray at the time of his Pulitzer announcement in 1990, saying: “If you think we are just going to sit here and accept the fact that we are never going to be half the sportswriter you are, well, all I have to say is, mister, you are right.”

Other heavy-hitters of that current-day sports writing industry weighed in similarly.

Rick Reilly, a Times colleague who moved on to Sports Illustrated: “Columns are like riding a tiger. You’d like to get off but have no idea how. I cried Monday when Murray found a way.”

Ross Newhan, a member of the writers’ wing of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, recounted sitting with Murray at a World Series game, in a far-off press box, up high, in a cold wind and with vision blocked by a foul pole: “Murray wrote, ‘I’m told the Kansas City Royals won the game, but don’t take my word for it. A chicken rancher from Petaluma with a 9-inch screen got a better view of the game than I did.’ ’’

The late Mal Florence, longtime USC and Rams’ beat writer for the Times, recalling the day the Rams were trailing the Vikings at halftime 31-0, and Murray was asked to go on the radio: “The announcer introduced him snidely, by saying, ‘Well, here’s the famous Jim Murray. Say something funny, Jim.’ Murray didn’t even pause. He said, ‘The Rams.’ ”

Scott Ostler, formerly of The Times and now an 11-time California sportswriter of the year with the San Francisco Chronicle: “I grew up as a sports fan in L.A., wanting to do two things: 1, Read Jim Murray every morning; 2, Write like Jim Murray. Goal-achievement-wise, I batted .500. You can’t write like Murray any more than you can sing like Sinatra.”

Bill Plaschke, who currently holds Murray’s spot at the paper: “In a busy town of big shots, Murray saw the lone guy, walking to the newspaper box, with a quarter in his hand, the guy who had no choice but to trust him.”

Thomas Bonk, award-winning columnist in Houston and longtime Times golf writer: “I never knew Joe Louis or Babe Ruth or Vince Lombardi. But I did know Jim Murray. In the writing business, Jim hit home runs, scored knockouts and won Super Bowls every time he sat down to write.”

Pete Thomas, former Times outdoor writer, who drove Murray around during the 1984 Olympics: “I learned why he needed a driver that first night, pulling into his garage to drop him off and seeing, in the beams of light, a washer and dryer that were full of dents. ‘That’s how I know when to stop,’ ” Murray said.

Murray was at the 1989 World Series in San Francisco, when the earthquake hit. As buildings crumbled and bridges fell, the power went out. It became a scramble for power, certainly for anybody trying to send a story via a laptop computer. The late Edwin Pope, a star columnist at the Miami Herald, told the story of what took place. Pope and Murray and several other writers departed the stadium, leaving all the dead phones behind. They drove south down Highway 101 until they spotted a phone booth with the lights on. If nothing else, they could call their offices and dictate what they had written.

Pope went before Murray, because his paper was in the Eastern time zone. As he was wrapping up and getting ready to make way for Murray, who was waiting nearby, a husky type with a heavy beard, tattoos and a leather jacket rolled in on his Harley and headed directly for the phone booth.

As Pope told it, “This guy came right at me. He was huge. He looked angry, even mean. I figured he wanted to use the booth, was in a hurry and I was in his way. I thought this might be my last moment on Earth. He pulled open the door, stuck his head in and said, pointing to his left, ‘Hey, is that Jim Murray over there?’ ”

Murray was, in so many ways, more than just a guy going to games and writing clever lines about them. He wrote for Time and Life Magazine when he first came to Los Angeles, and he interviewed much more than sports stars. While he was interviewing Marilyn Monroe at dinner one night, he noticed that her attention was more on some guy sitting in a back booth. He told her he would cut the conversation short if she would take him back and introduce him to Joe DiMaggio.

At the time of his death, many non-sportswriters weighed in as enthusiastically, and sadly, as had his colleagues:

John Wooden: “I knew him better as a person than writer, and I just liked that person.”

Former President, Ronald Reagan: “He gave us a slant we couldn’t get anywhere else. He will be missed.”

Jerry West: “He was not only the best sportswriter I have ever known, but one of the best men, period.”

John McKay, recalling with a chuckle what Murray wrote after his USC football team had beaten a heavily favored Notre Dame: “Murray wrote, ‘All right, who’s the wise guy who ate meat on Friday?’ ”

Sandy Koufax: “Murray was a man who could see the humor in both himself and those he wrote about.”

Then-Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan: “Jim Murray was a great intellect, a great wit and a crusty curmudgeon…the sports pages of The Los Angeles Times will never be the same again.”

Vin Scully, about whom Murray wrote: “Vincent Edward Scully meant as much or more to the Dodgers than any .300 hitter they ever signed, any 20-game winner they ever fielded. True, he didn’t limp to home plate and deliver the home run that turned a season into a miracle — but he knew what to do with it so it would echo through the ages.” At Murray’s death, Scully said, “Every day, he faced the same challenge, the same blank piece of paper, tauntingly unfurled and hanging out of the typewriter like a mocking tongue, daring him to be different, fresh, funny and incisive. And every day, for more than 35 years, Murray not only accepted that challenge, but triumphed.”

Nothing and nobody were sacred with Murray, and his one-liners remain legendary today:

At Indy: “Gentlemen, start your coffins.”

After a visit to Cincinnati: “They still haven’t finished the freeway. It’s Kentucky’s turn to use the cement mixer.”

After a visit to the state of Washington: “The only trouble with Spokane as a city is that there is nothing to do after 10 o’clock. In the morning.”

On San Francisco: “It is so civilized it would starve to death if it didn’t get a salad or the right wine.”

But Murray’s most famous columns were serious, life-jarring commentaries: (1) When he temporarily lost his eyesight to the detached retina, he called it the loss of “old blue eye,” and people quoted from that for years. And (2), when his wife, Gerry, died, he wrote: “This is the column I never wanted to write, the story I never wanted to tell…I lost the sunshine and roses, the laughter in the other room.” That triggered a flood of tears in a major metro city.

One of his most memorable moments was the time Hollywood honored him, at the Beverly Hilton Hotel, after he won the Pulitzer. It was a black-tie event. Huge crowd. Lots of glad-handing and people there to be seen before they wrote big checks for the charity. Merv Griffin ran the show, and why not? He owned the hotel. Sammy Cahn revised some lyrics and turned it into: “I’m just wild about Murray.” Murray sat at a front table, a little uncomfortable in his tuxedo and a lot uncomfortable about being this much in the spotlight.

Finally, Griffin said there was one more surprise. He called Murray to the stage and had him turn around. Standing there were Ronald and Nancy Reagan, who placed a medal around his neck. The crowd went wild, the applause went on and on, the former president and first lady departed and there was Murray, standing alone and knowing he had to say something significant, or at least something clever. So he did. He looked out at the audience, got a little wide-eyed and said:

“Did I die?”

Less than a decade later, he did. And Los Angeles will never be the same.

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.