The pandemic’s toll:Lives lost in California

Updated

Thousands of lives have been lost in the coronavirus outbreak, in cities and small towns, in hospital wards and nursing homes. The virus has moved across California, killing the old and the young, the infirm and the healthy.

Some patterns have emerged. Large metropolitan centers such as Los Angeles and San Francisco appear to be the hardest hit. More than 63 thousand people have died in California. These are some of their stories, reported by Los Angeles Times staffers and six interns here through partnerships with the Pulitzer Center and USC.

Michael Ayala

66, Sonora

Penny Foreman

73, Clovis

Alfonso Ye Jr.

25, Chula Vista

Vic Lepisto

75, Agoura Hills

Frederick K.C. Price

89, South Los Angeles

Taurino and Silvia Rivera

57 and 56, San Diego

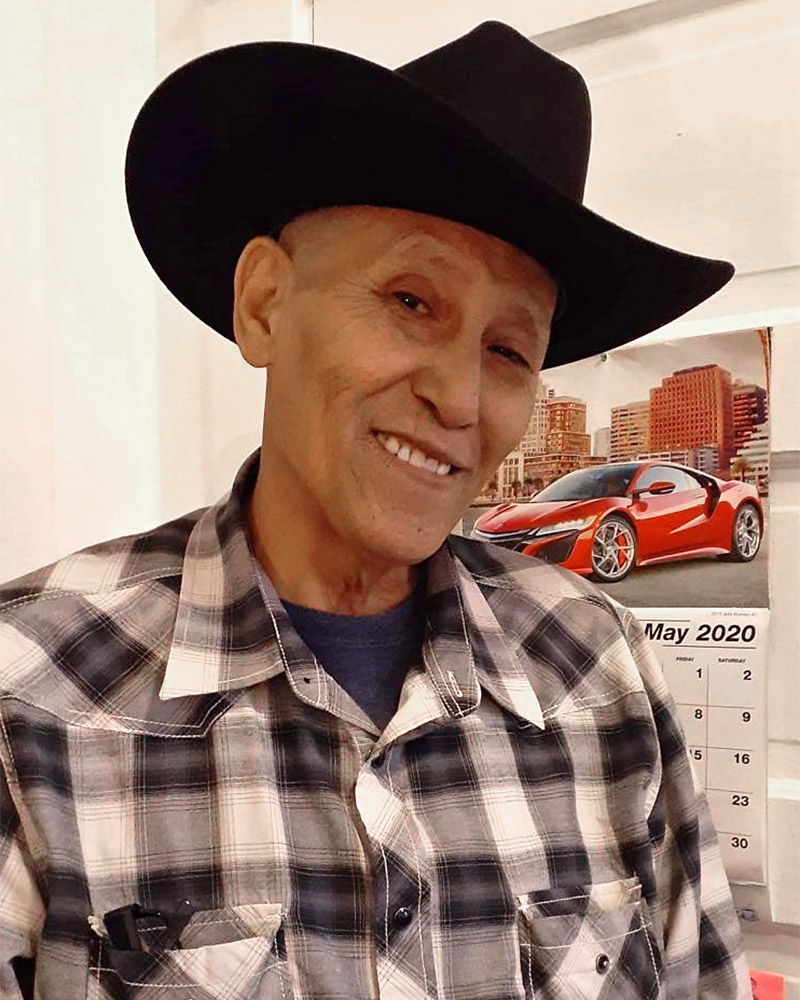

Vidal Garay

60, Los Angeles

Brittany Bruner-Ringo

32, Torrance

William Minnis

70, Hayward

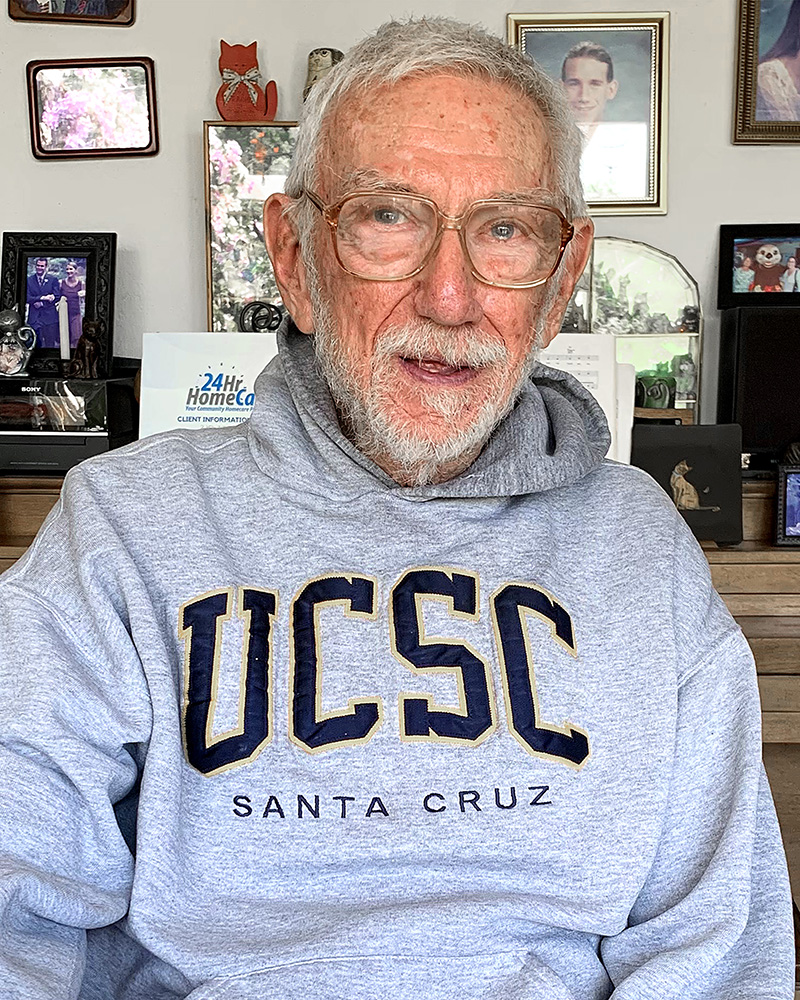

Richard Rutledge

87, Folsom

Raul J. Arce

87, El Centro

Desanka Mitrovich

95, San Diego

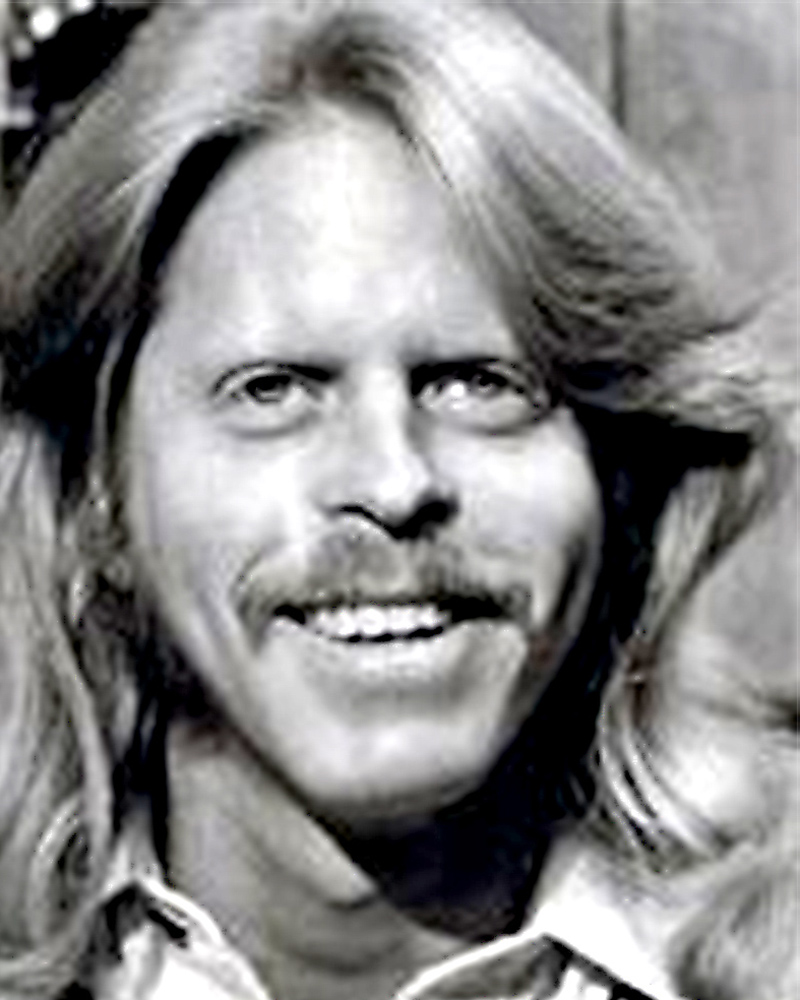

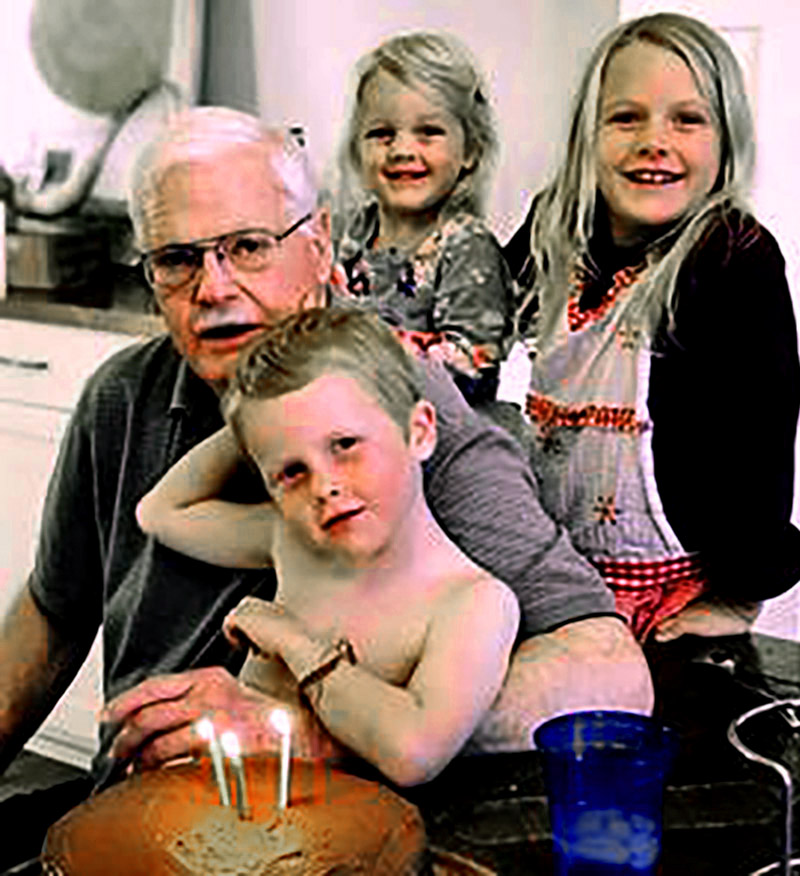

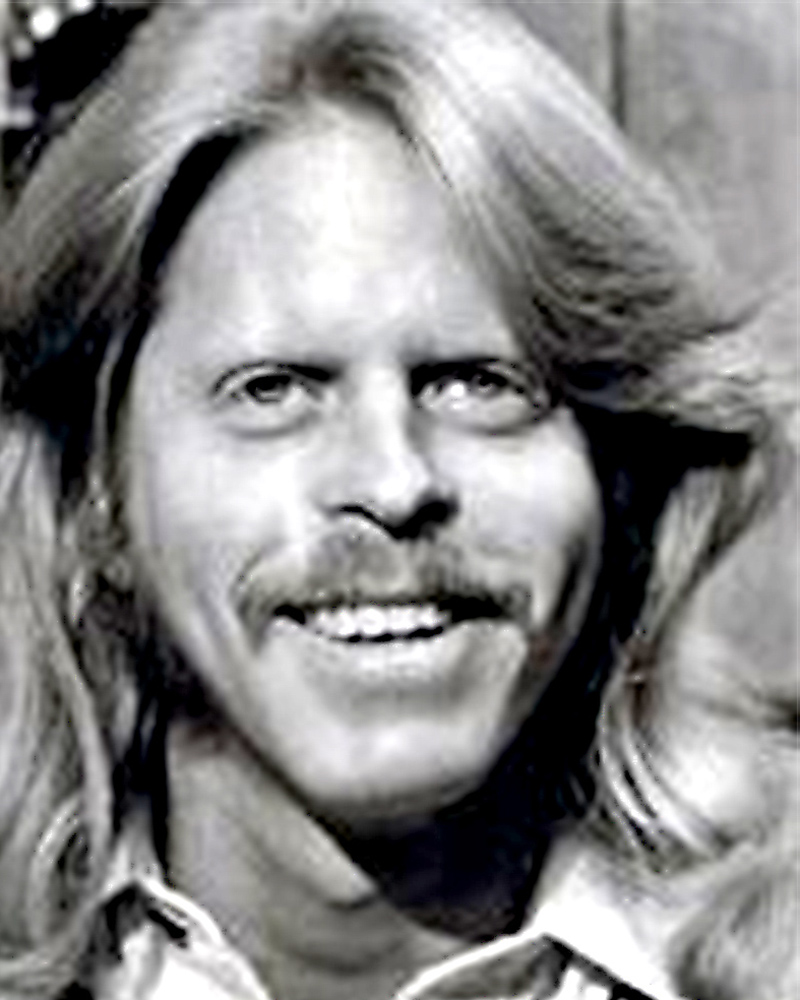

Gary Young

66, Gilroy

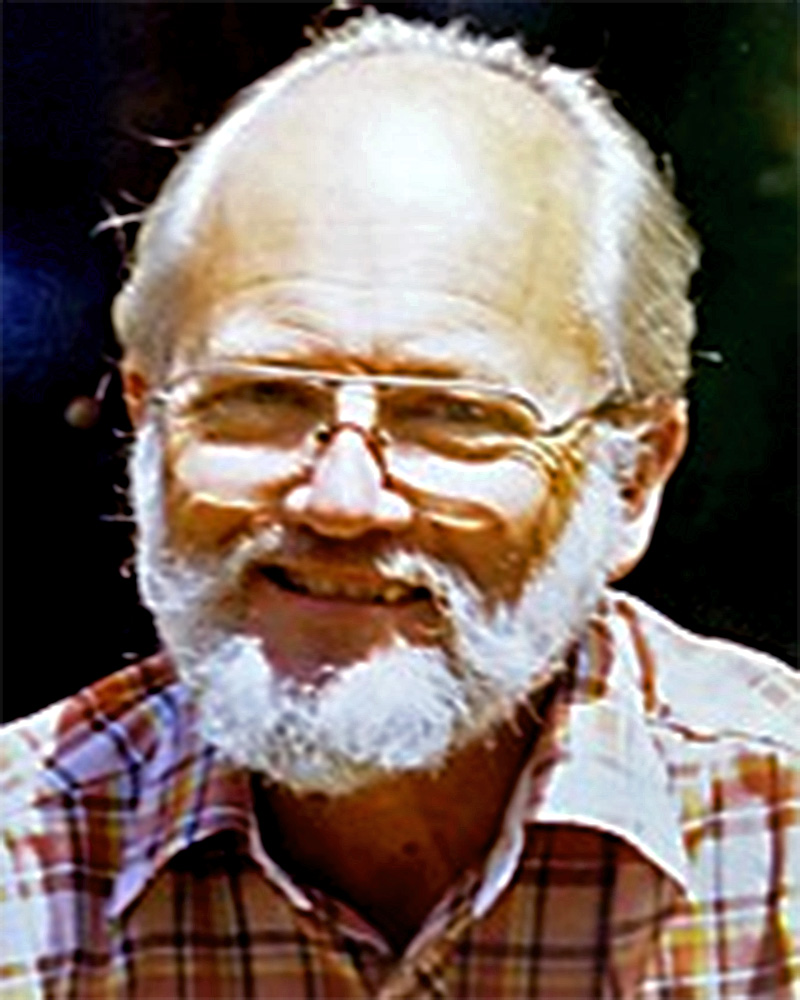

Mike Gotovac

76, Los Angeles

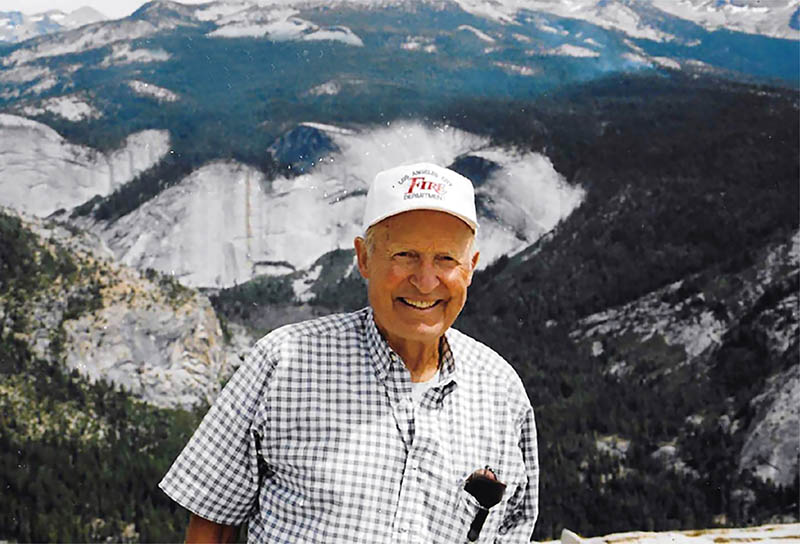

Ralph Duprey

98, Signal Hill

Ever A. Linares

45, Los Angeles

Barbara Johnson Hopper

81, Oakland

Ronda Felder

60, San Diego

Carol van Zalingen

53, Sylmar

George Chiu

86, Palo Alto

Ronald Harris

82, Los Angeles

Paulita Bernuy

91, Encino

Patti Breed-Rabitoy

69, Reseda

Mark Appelbaum

79, San Diego

Rose Cadena Lord

83, Yucaipa

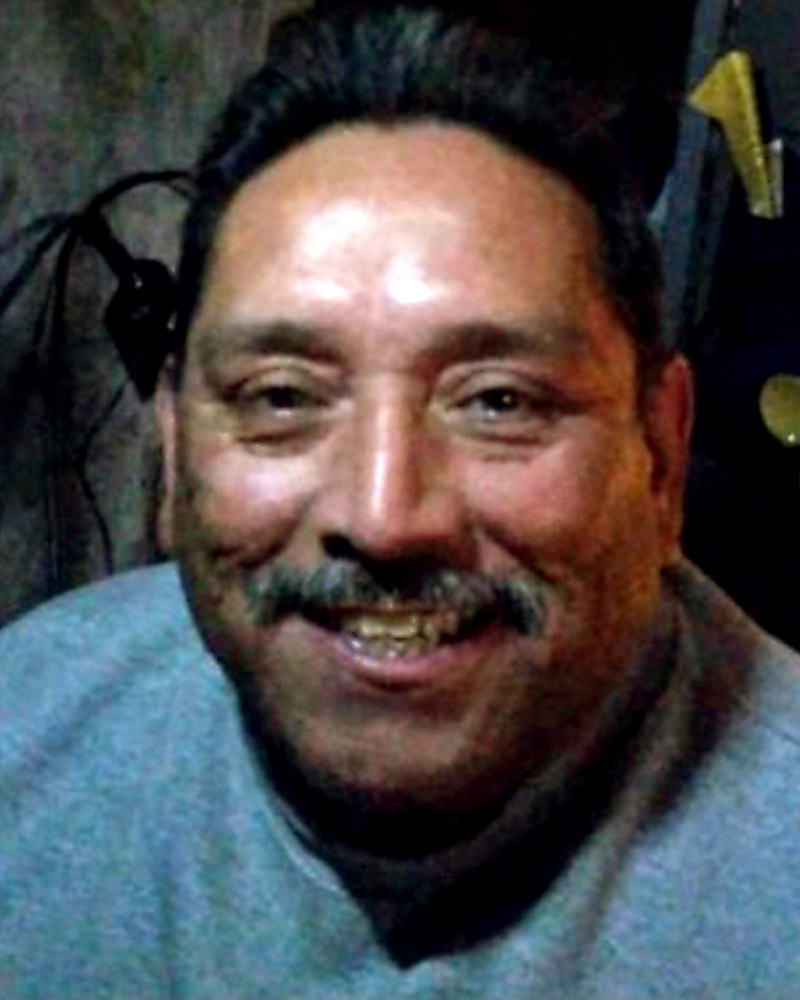

Carlos Oropeza Canez

60

Emma Patiño

84, Hayward

Tran Ngoc Chau

96, Los Angeles

Costelle Akrie

88, Hayward

Tommy Macias

51, Lake Elsinore

Michael Cook

84, Los Gatos

June Pantages

96, Pleasant Hill

Vernon Robinson

81, Burbank

Mary Miramontes

90, Danville

Loretta Mendoza Dionisio

68, Orlando, Fla.

Joyce Marie Pierce Johnson

71, Houma, La.

Bishop Anthony Pigee Sr.

49, Los Angeles

Cornelia Talbott

75, Brawley

Alan Beal

80, San Jose

Oscar Leonel Rosa

25, Bell Gardens

Margaret Lucille Romero

73, Big Pine

Andy Marin

38, Porterville

Ken Caley

59, San Clemente

Margaret Zwingman

98, Salinas

Wayne L. Strom

85, Thousand Oaks

Mario Leos Lomeli

93, Los Angeles

Theodore “Ted” Lumpkin

100, Los Angeles

Gloria Martinez

91, Visalia

Joni Berry

89, Los Angeles

Luz and Israel Teicher

85 and 85, Stockton

Rosa Luna

68, Riverside

Tara Fay Mitchell

63, Sacramento

Melinda Wernick

78, Palm Springs

Antelmo Candido Garcia

65, Pasadena

Jose Valero

35, Los Angeles

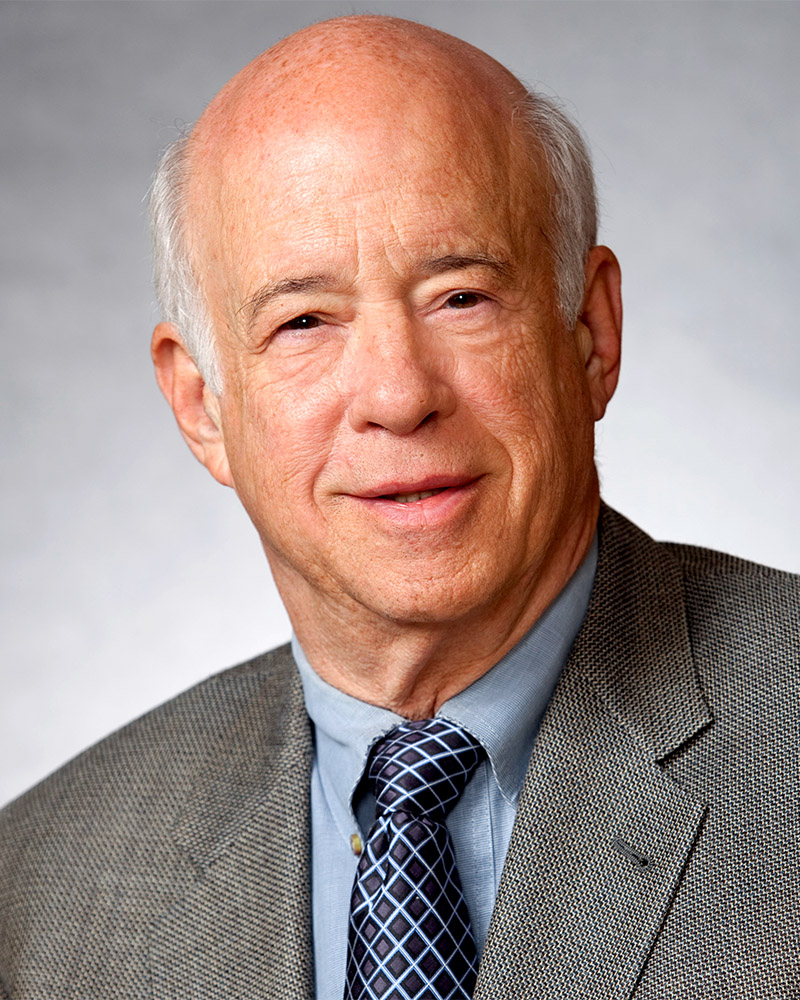

Leonard Auerbach

73, Terminal Island

W. David Stern

93, Mill Valley

Evelia B. Rubio

54, Colton

Anne Lehner

96, Encino

Marylou Armer

43, American Canyon

Angel De La Fuente

49, Fresno

Scott Blanks

34, Whittier

Stephen Butters

90, Alta Loma

Carmelita and Federico Calindas

77 and 82, Sacramento

Paul Hernandez

62, East Los Angeles

Bill Kling

51, Camarillo

Larry T. Baza

76, San Diego

Sallie Jones

86, San Diego

Catherine Apothaker

89, Los Angeles

Alex Bernard

57, Downey

Jose M. Perez

44, Lakewood

Samira Al-Hadad

84, San Luis Obispo

Donald Wickham

94, Watsonville

Wanda DeSelle

76, Madera

Susan Kam

94, Encino

Guillermo Ramirez

47, Azusa

Ron Rowe

83, Hollywood

Margarito Guillén

71, San Pablo

Crispin Rojas Ortega

82, Montebello

William Z. Good

96, Azusa

Harry Sentoso

63, Walnut

Herbert Segall

91, Pasadena

Alby Kass

89, Guerneville

Pedro Zuniga

52, Turlock

Elsa Claybaugh

84, Clovis

Lawrence Wilkes

80, Anaheim

Lourdes Pizarro

62, Gilroy

Artemio Ramos

77, Reseda

Stan Westmoreland

76, Lemon Grove

Arcelia Martinez

65, San Jose

Nicholas Dees

54, Vallejo

Russ Abraham

70, Fair Oaks

Gabriel B. Zavala

76, Anaheim

Mark Scheu

53, Moorpark

Joseph Radisich

84, San Pedro

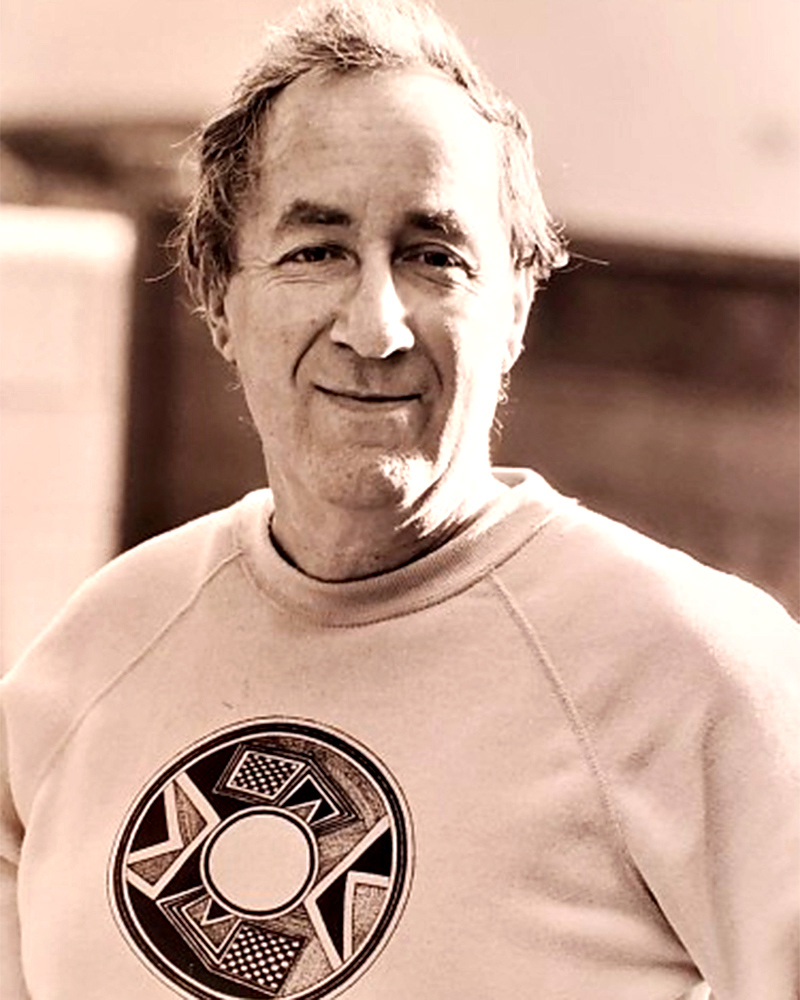

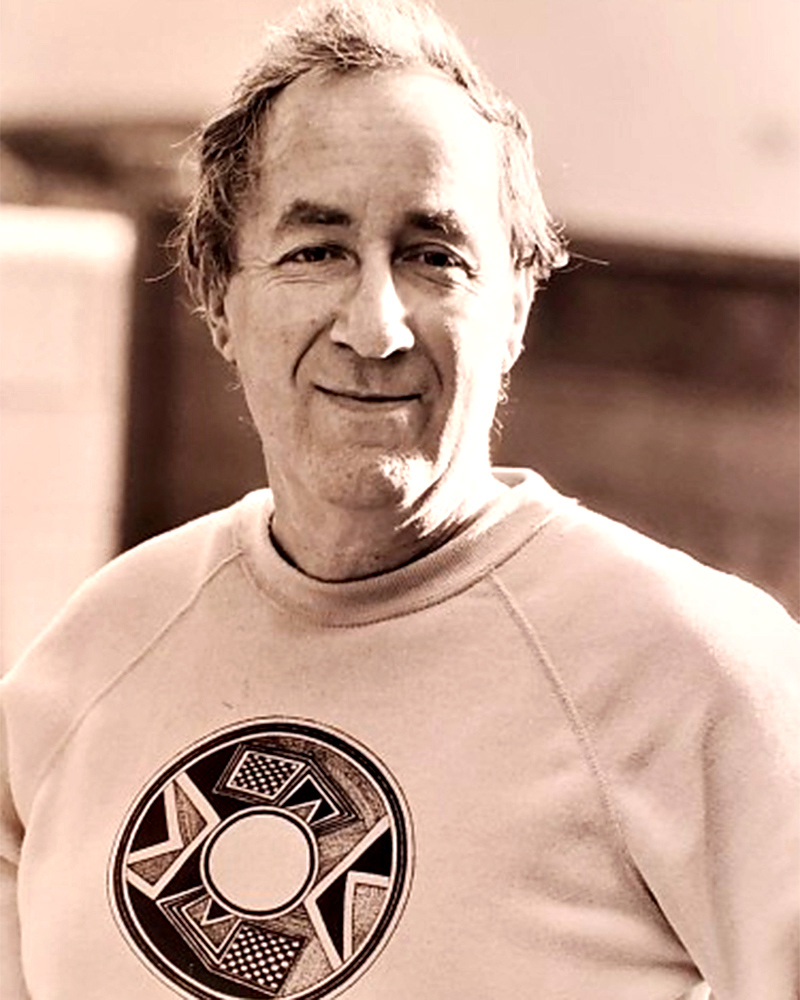

Gerald Locklin

79, Long Beach

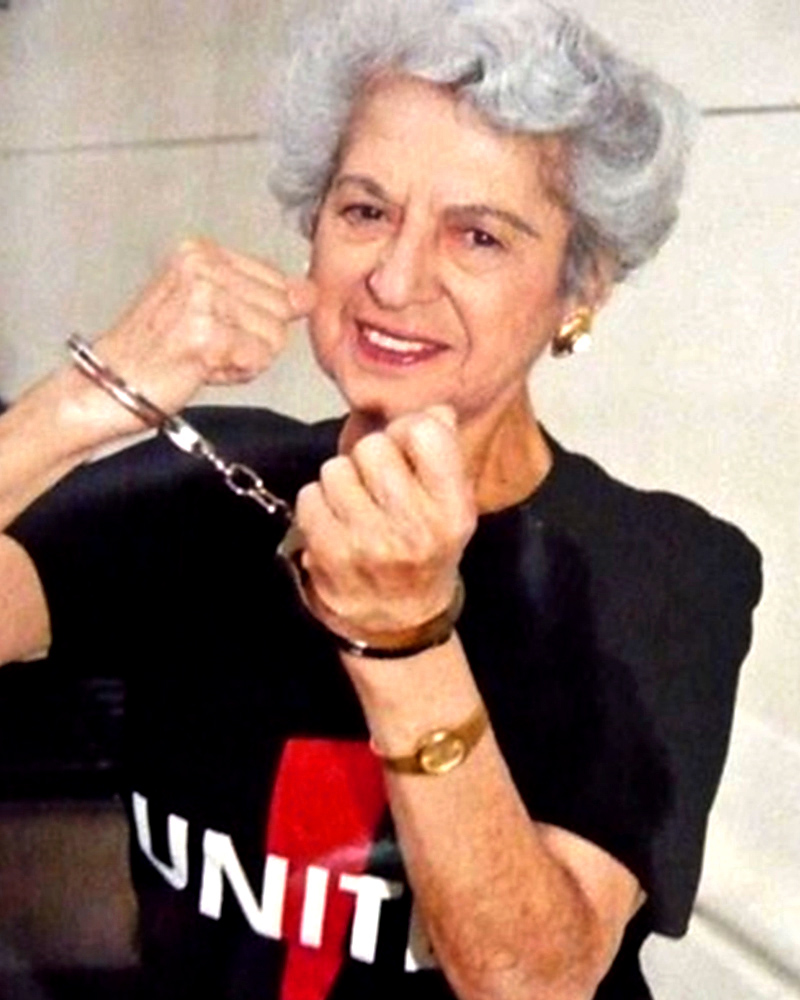

Carolyn Buhai Haas

94, Tiburon

Jo Ann Smith

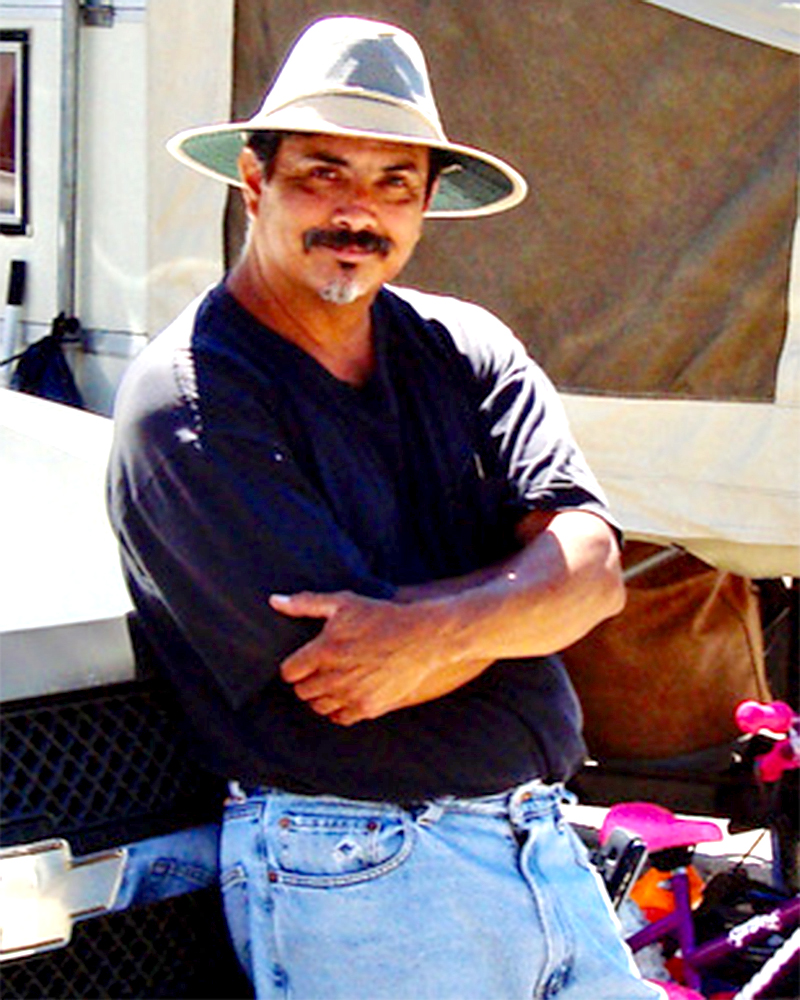

66, Pala Indian Reservation

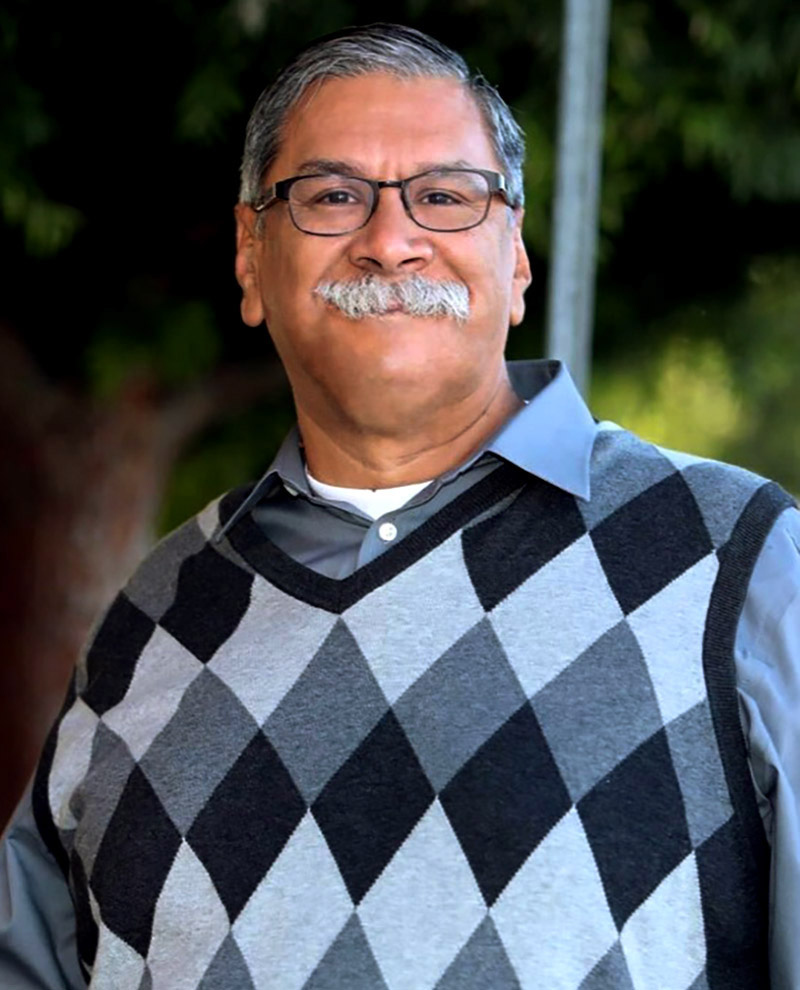

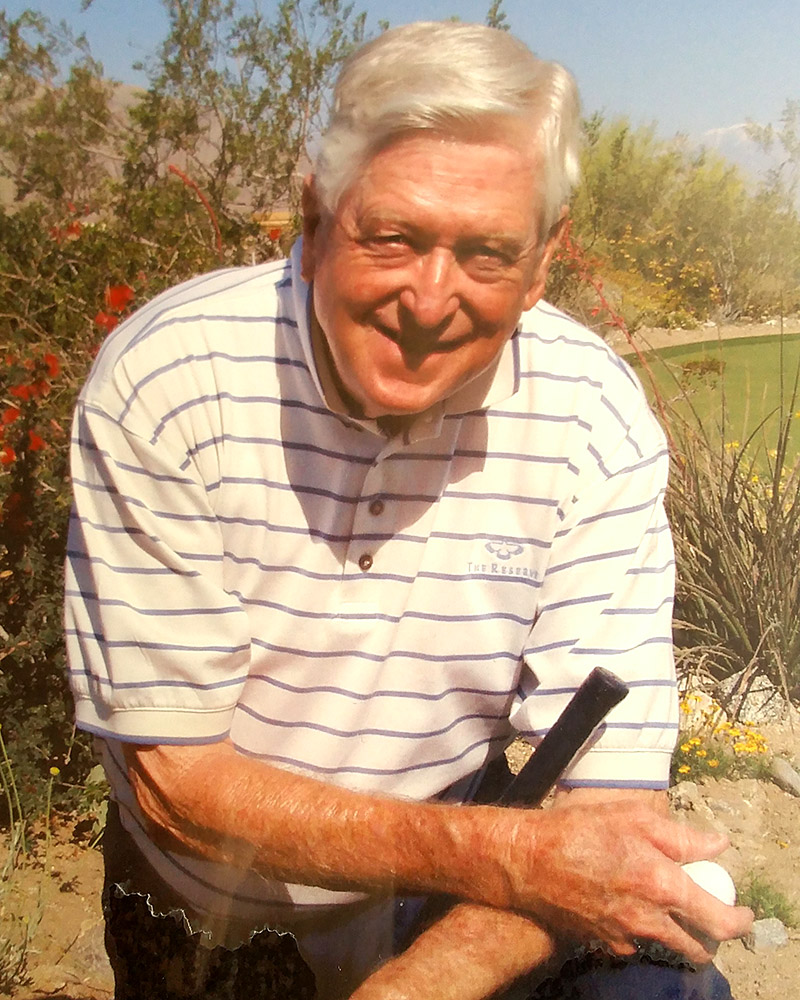

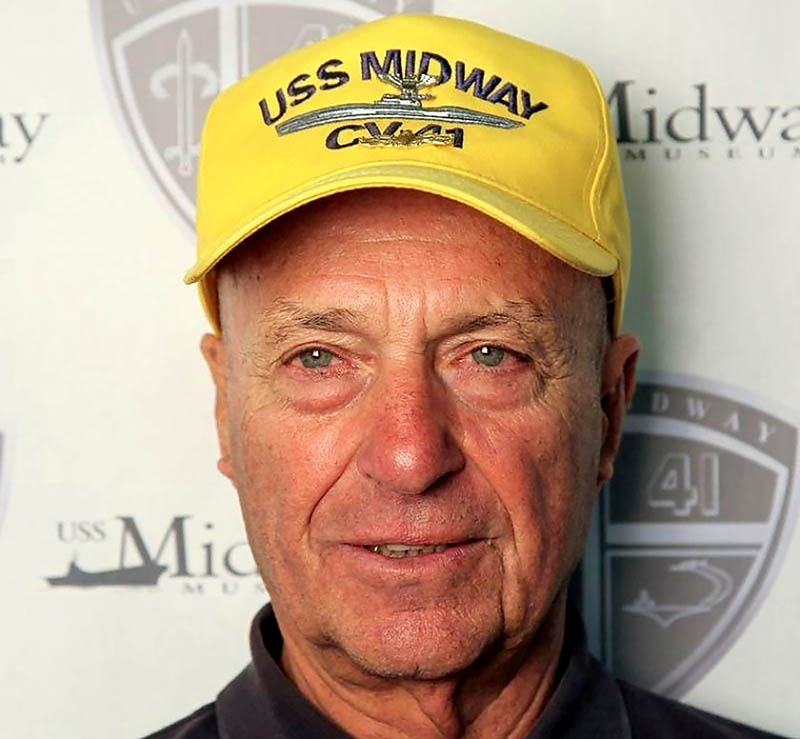

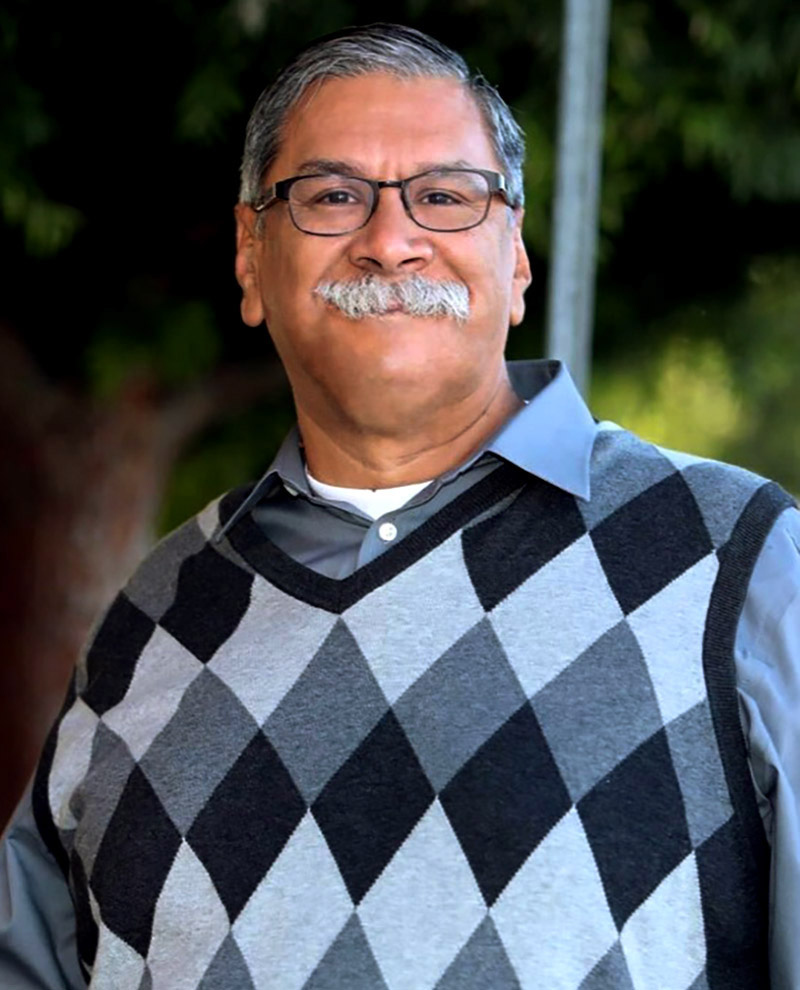

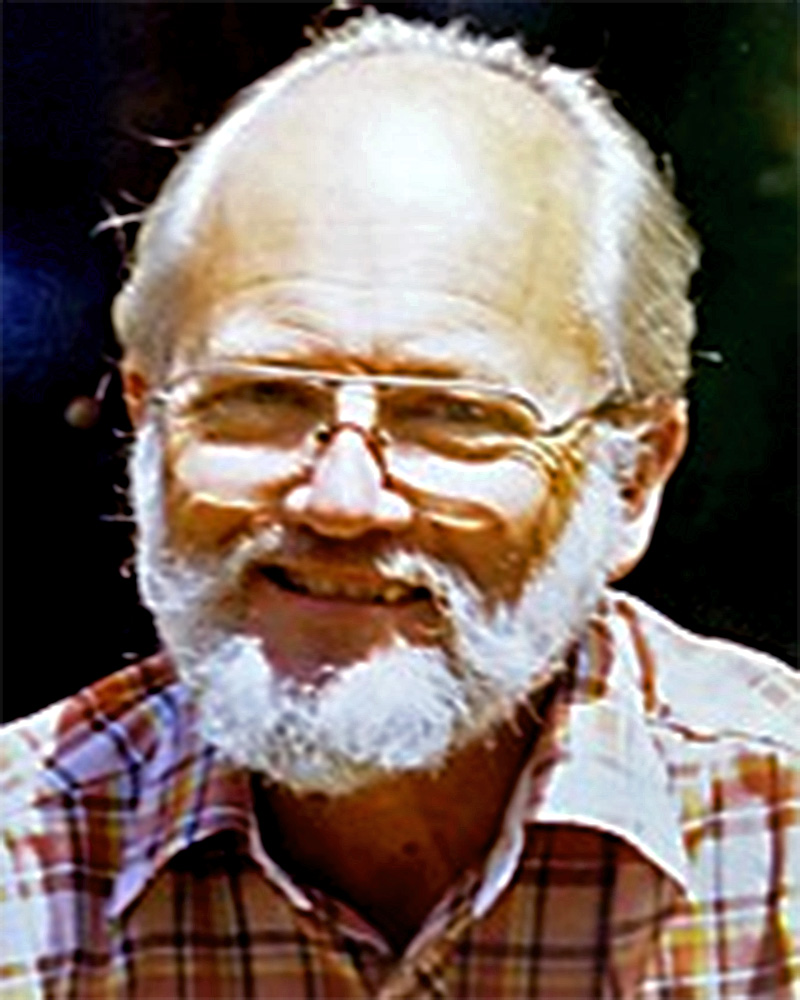

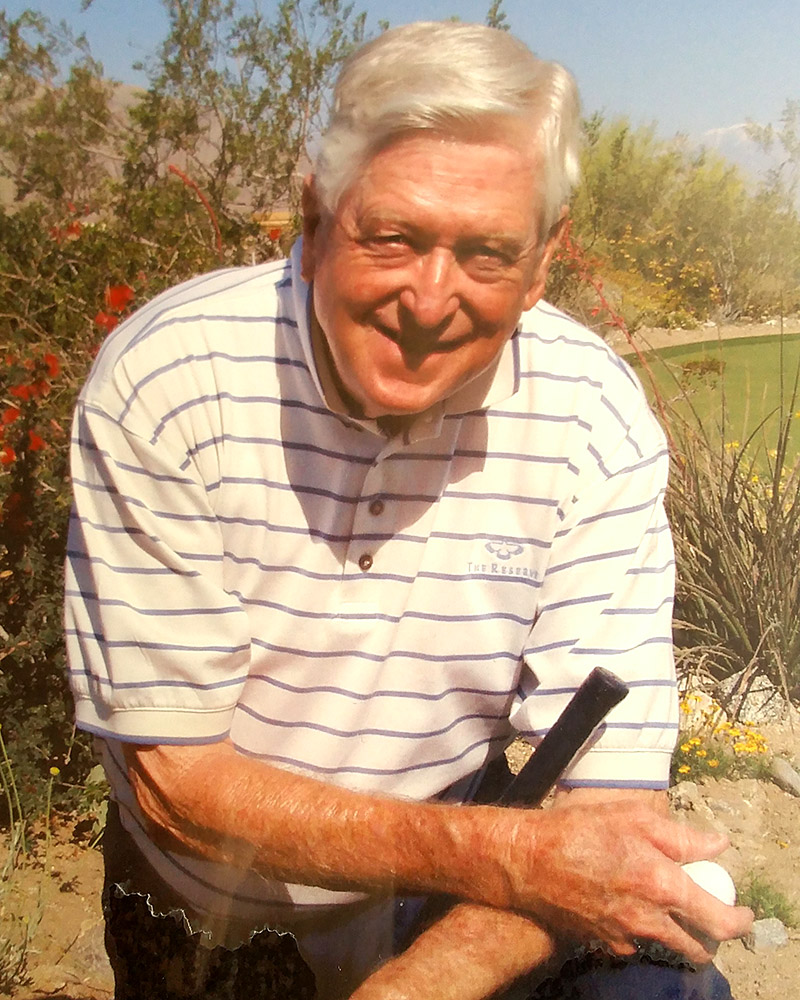

Kermit Holderman

73, San Diego

Jorge Martinez

53, Los Angeles

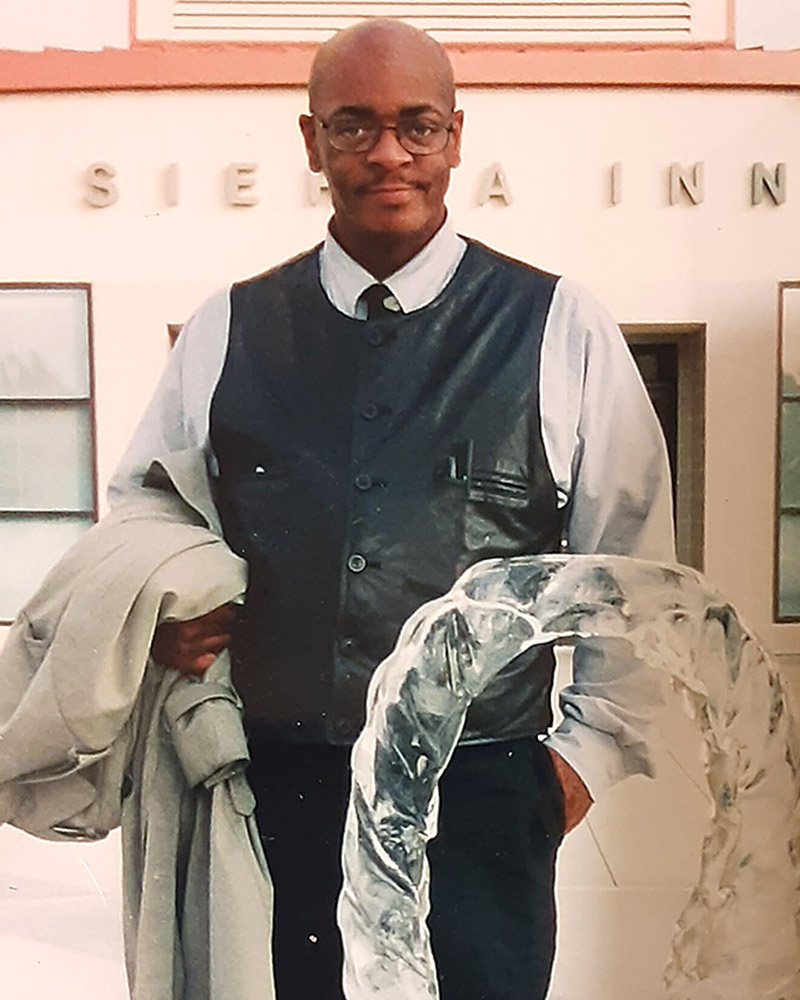

Terrell Young

52, Murrieta

Janet Carvalho

83

Dr. Ernesto Victor Sotto Santos

47, San Dimas

Leslie Hagan-Morgan

38, South L.A.

Merrick “Jenks” Dowson

67, San Francisco

Julio Ramirez

43, San Gabriel

Tony M. Sanchez

73, Tulare

Jose Roberto Alvarez

67, Los Angeles

Dolores Shoebotham

88, San Diego

Mary Palos

105, Claremont

A. Charles Kratz

76, San Diego

Rafael Cartagena

66, San Fernando

Juan Martinez

36, Stockton

Trini Lopez

83, Palm Springs

Azar Ahrabi

68, Santa Clara

Robert Brewster

88, Rancho Palos Verdes

Alice Coopersmith Furst

87, Kentfield

Jeff Baumbach

57, Lodi

Frank J. Duran

88, Ventura

Dave Browner

78, Los Angeles

Marcia Burnam

92, Los Angeles

Harold Budd

84, Pasadena

Terry Blanchard

56, Oakland

Noe Montoya

66, Hollister

Ronald Shirley

80, Camarillo

Joel Rogosin

87, Woodland Hills

Frederick W. Cook

88, Stockton

George Whitmore

89, Fresno

Manuel Agredano

83, Lawndale

Jack B. Indreland

94, Los Angeles

Bayron Salguero

30, Los Angeles

Cindy and Ruben Trejo

47 and 51, Inglewood

Len Fagan

72, Los Angeles

Otoniel Azañon Alvarado

48, Petaluma

Jacinto Abarca

59, Garden Grove

Douglas Borchert

77, Martinez

Cari Ramirez

45, Redlands

Winfred Grissom

91, Eureka

Marvin W. Carpenter

84, San Ysidro

Hy Cohen

90, Palm Desert

Adul Tangtam

64, Eagle Rock

Anthony Ragonesi

74, San Jose

Jeffrey Stark

62, Palm Springs

Raul Alaniz

53, El Centro

Manuel “Manny” Chagollan

89, Huntington Beach

Joseph Alexander

95, Hayward

Marie Cardoza Martin

99, Sacramento

Karen Hemm

69, Hemet

Antonio Bernabe

60, Van Nuys

Herbert J. Evers

88, Orange

Bernard J. Bush

86, Los Gatos

Miguel Perkins

71, Oceanside

Tessie Henry

83, San Francisco

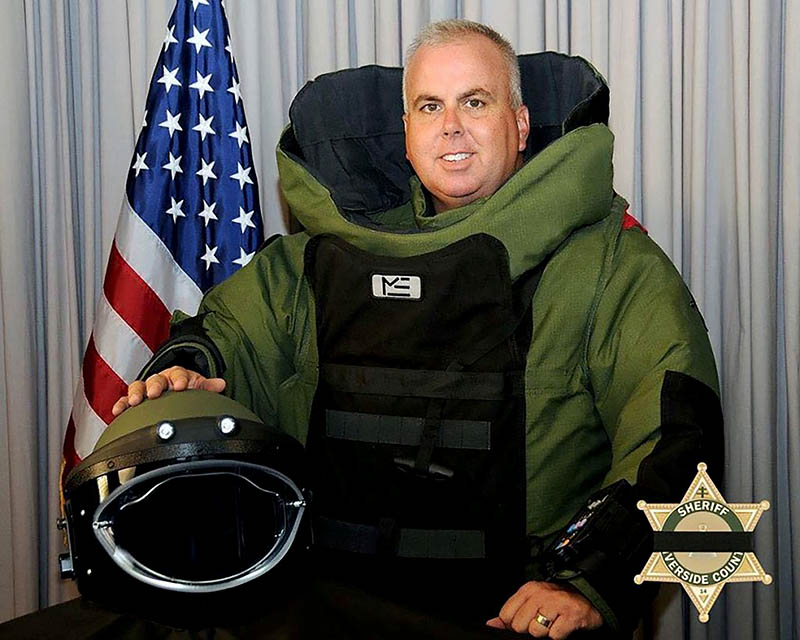

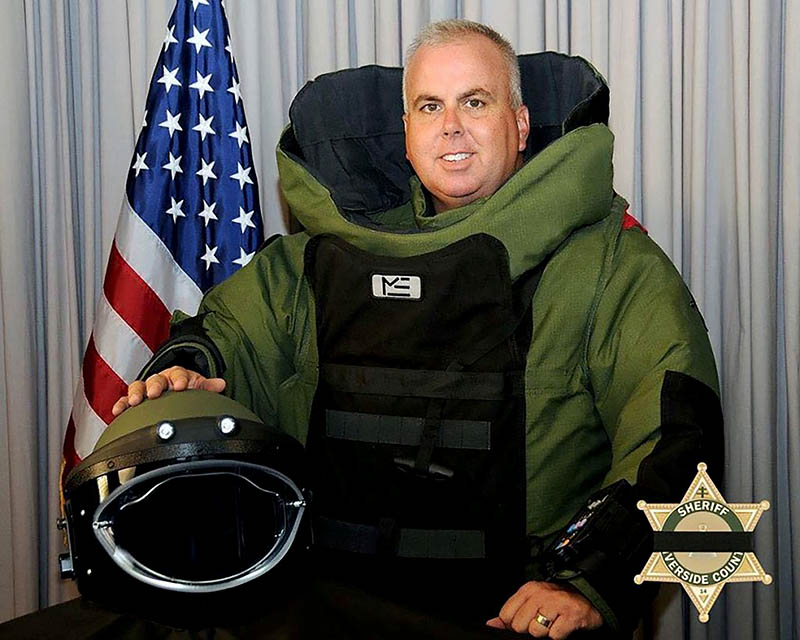

John Eric Swing

48, Westminster

Leland “Hobo” Goodsell

66, Goleta

John Fanucchi

79, Sanoma

Soon Sun Kim and Timothy Kim

85 and 68, Los Angeles

Gregory Bundy

65, Inglewood

Joseph Fice

82, Los Gatos

Karen Johnson

77, Beaumont

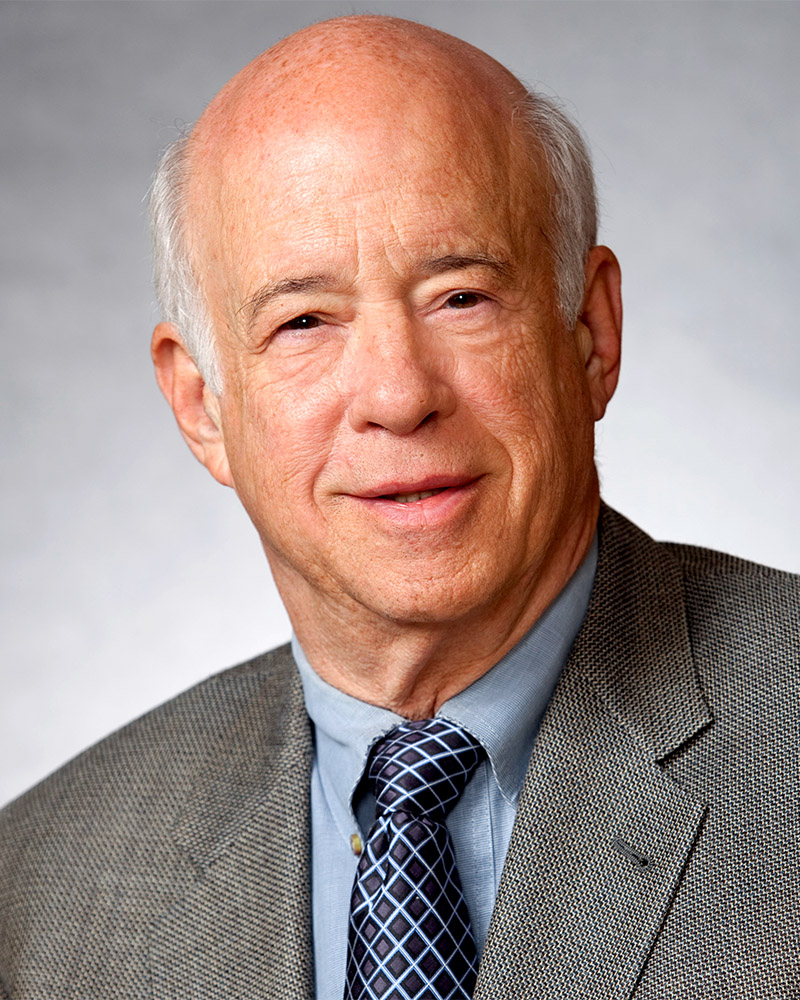

Julius Schachter

84, San Francisco

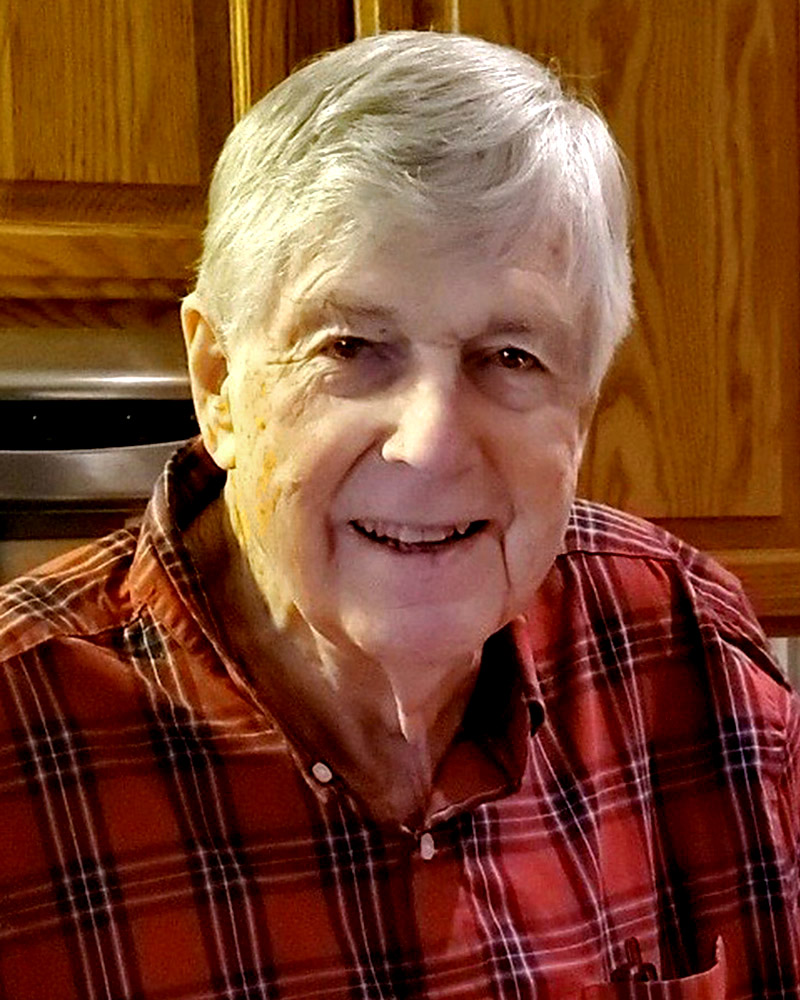

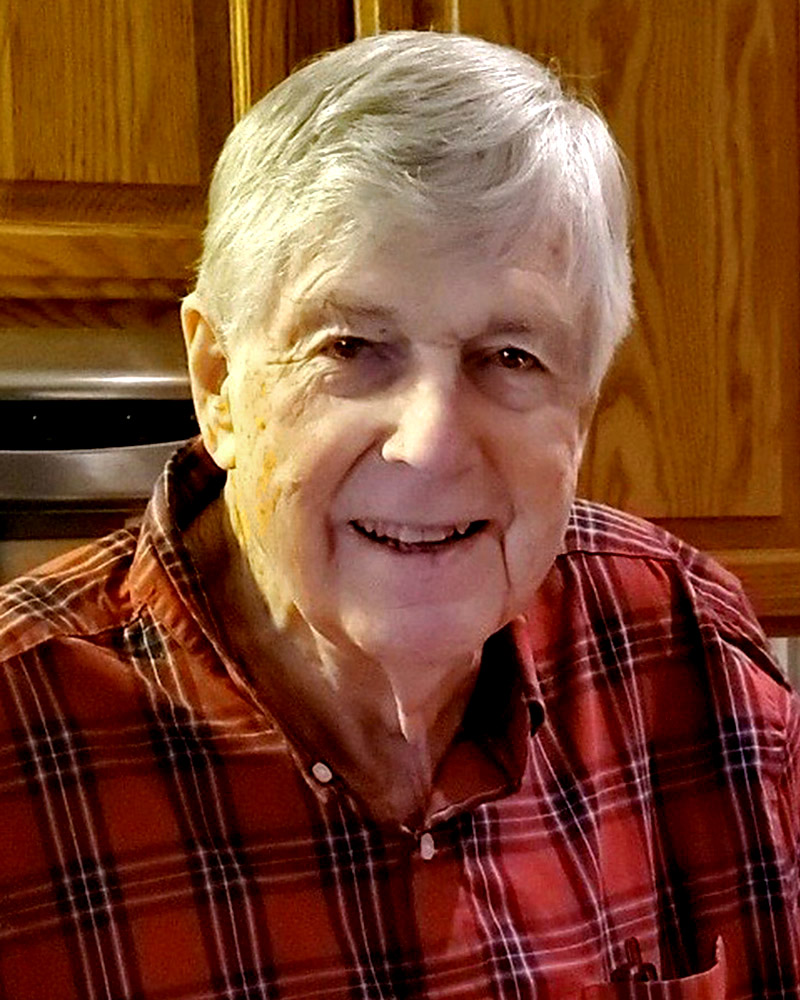

Daniel P. Barber

70, Palm Springs

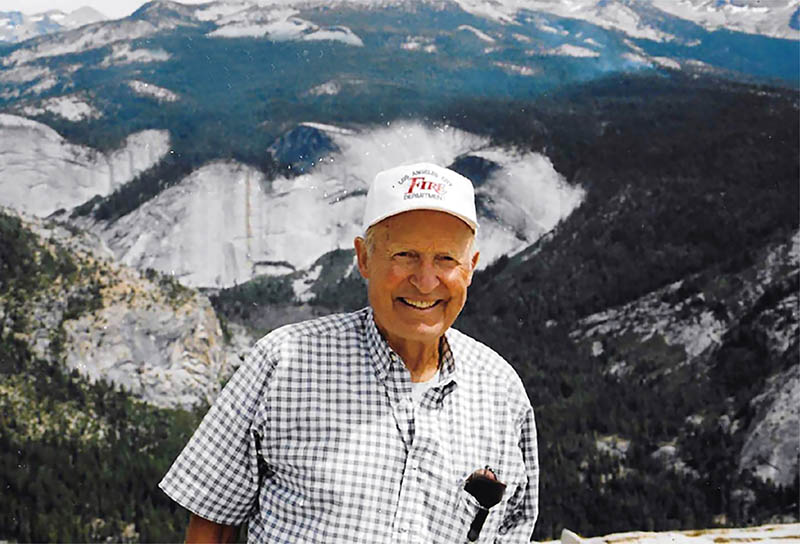

John Breier

64, Woodland Hills

Gerald Shiroma

59, Los Angeles

Kenneth Butori

71, Concord

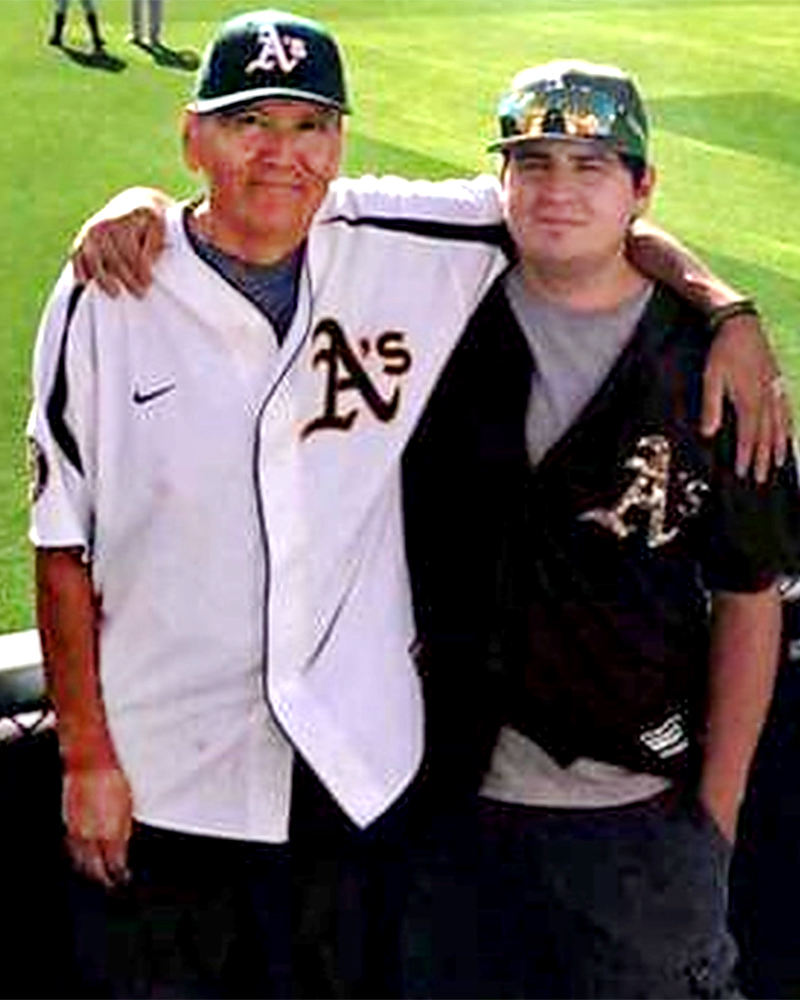

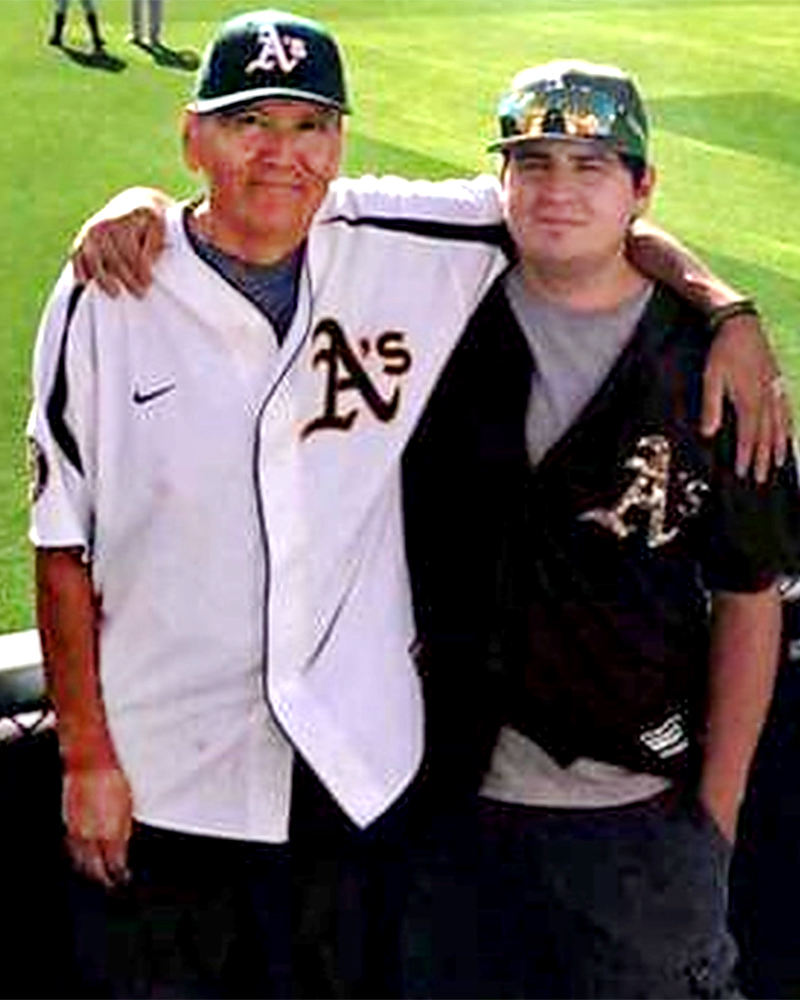

Dr. Manuel Ramirez

81, Montrose

Chris Trousdale

34, Los Angeles

David R. Dukes

76, Fullerton

Carol Ann Murphy

91, Vallejo

Hatsy Yasukochi

80, San Francisco

Richard Charles Bendel

75, Carpinteria

Jorel Alfonso

38, Riverside

Zella Campbell

94, Bishop

McHarry Watson

56, Mi-Wuk Village

Mary Joanne Rosario

87, Orange

Manuel Villanueva

67, Reseda

Dulce Amor Aguilo

55, San Jose

Florentina Lopez

66, Reseda

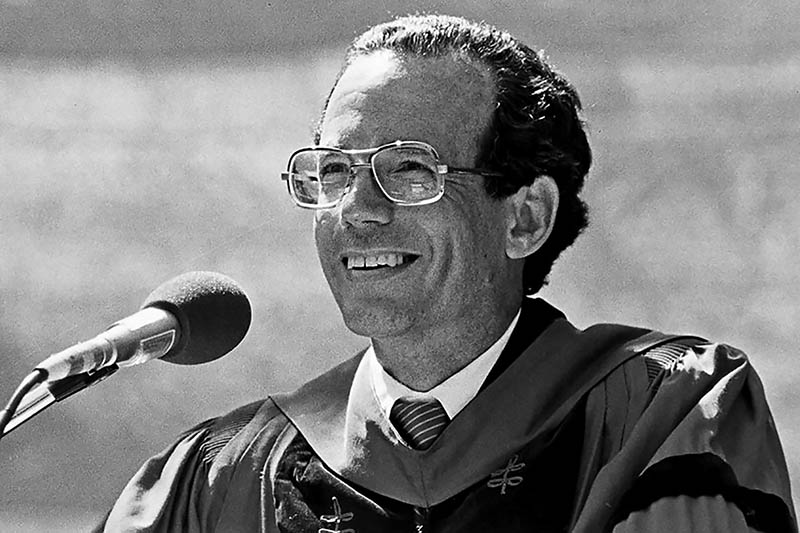

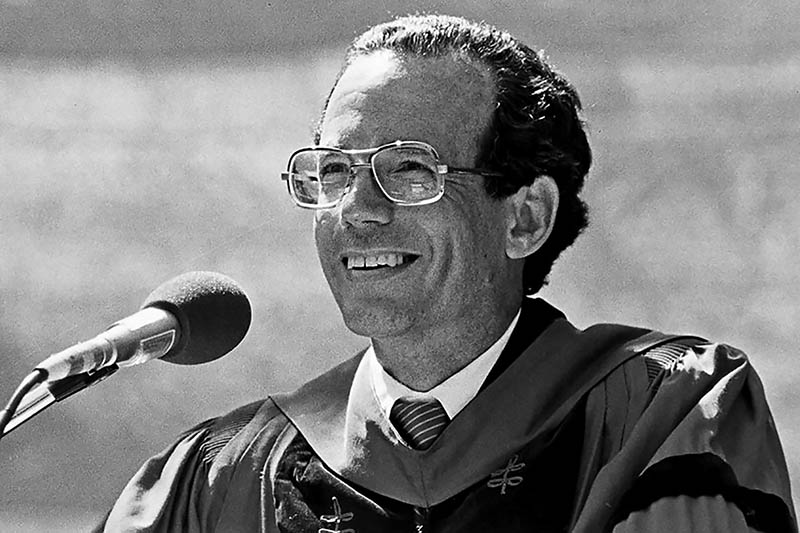

Donald Kennedy

88, Redwood City

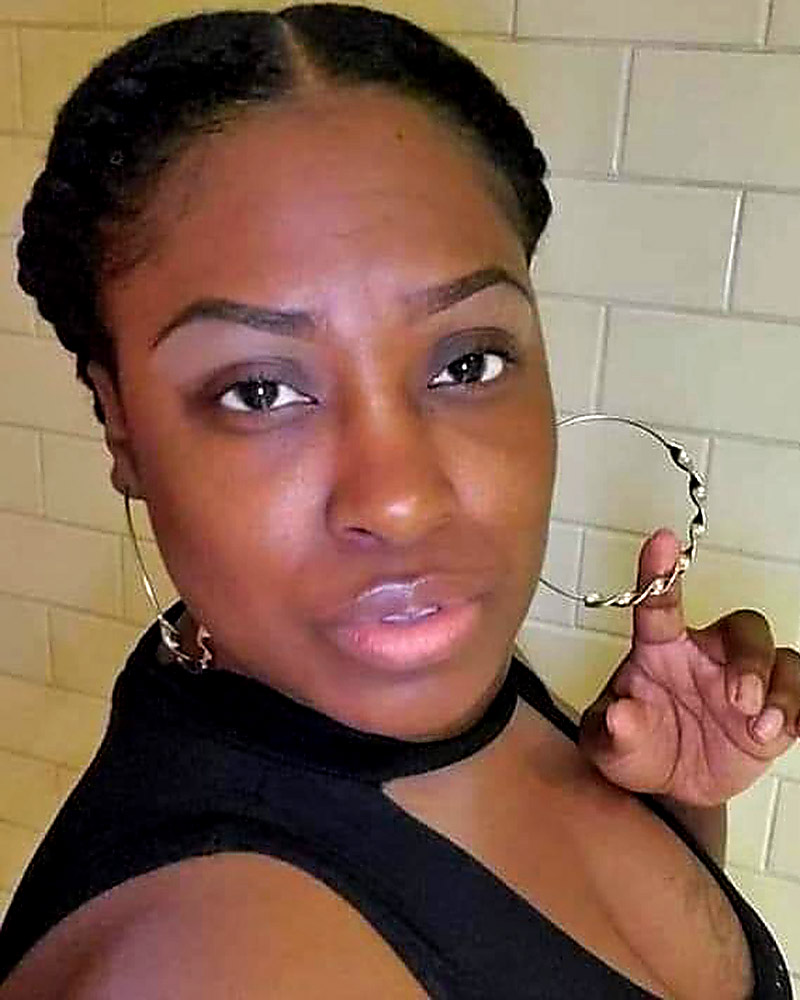

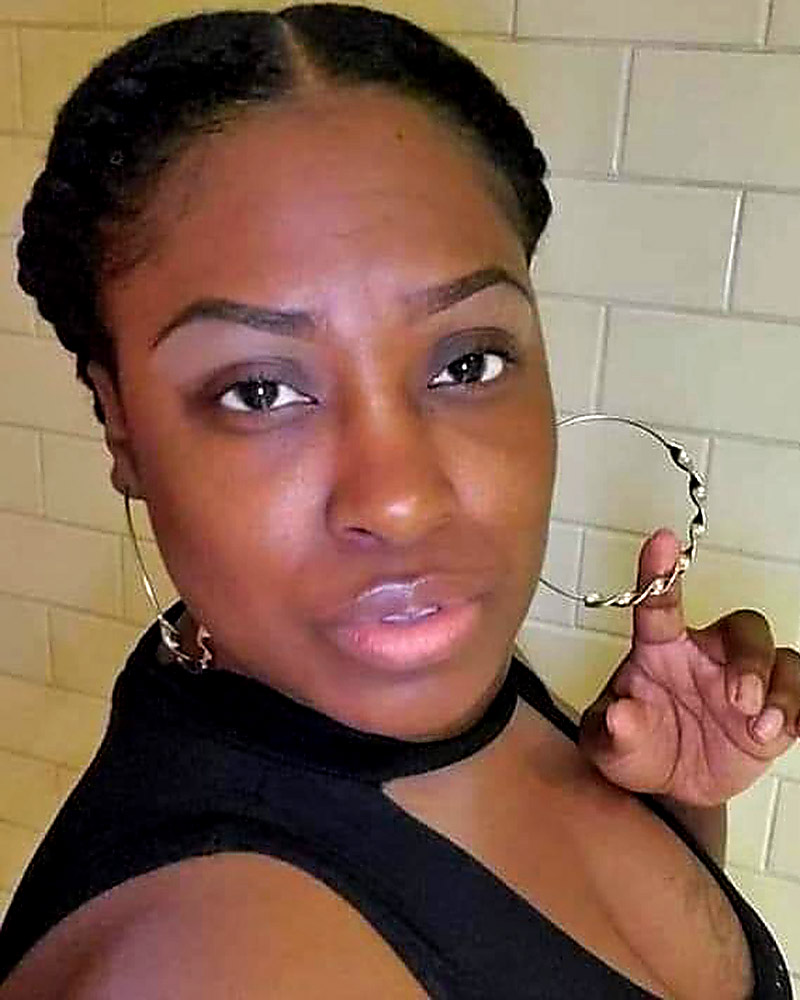

Erica McAdoo

39, Los Angeles

James Robert Waters

84, Sacramento

Scott Douglas Woodard

67, Oakland

Pauline Estey

97, Woodland Hills

Jim Farrell

69, Long Beach

Don Branker

75, Fresno

Lowell Parker Dabbs

95, Santa Barbara

Marc Wilmore

57, Claremont

Harold Widom

88, Santa Cruz

Ramon Arthur Rivera, Jr

56, Palmdale

Jack Turnbull

72, North Hills

John Patrick Doyle

62, Stockton

Gaby Elena O’Donnell and Greg O’Donnell

61 and 58, Whittier

Edmundo Raul Valencia, Jr

86, El Centro

Larry Robertson

72, San Pedro

Betty Gentry

94, Chula Vista

Francia Hernandez

77, Bakersfield

Valeria Viveros

21, Riverside

Joe Luna

38, Los Angeles

Irene Cornish Thompson

78, Rancho Santa Fe

Leeann Patterson

78, San Jose

Florence Schumacher

95, Fair Oaks

Garry Bowie

59, Lakewood

Carolina Tovar and Letty Ramirez

86 and 54, Rowland Heights

Milton Melzian Jr.

89, Aptos

Margaret Sowma

105, Los Angeles

Nick Cordero

41, Los Angeles

Glenn McGihon

90, Palm Desert

Rose Matsui Ochi

81, Los Angeles

Ronald Burdette Culp

84, Redding

Robert Pinedo

64, Brawley

Wilson Maa

71, San Francisco

Patsy Merrill Nelson

94, San Mateo

Ann Sullivan

91, Woodland Hills

Rosary Castro-Olega

63, Los Angeles

David Werksman

51, Corona

Baltazar Aguirre

64, Coachella

George Bender

88, Rancho Palos Verdes

Lola Mae Roach Larson

95, Carlsbad

Shawki Zuabi

64, Laguna Niguel

Elizabeth Yamada

90, La Jolla

Robert Mendoza

43, Oceanside

Rafael “Ray” Vega

86, Sherman Oaks

Terese Chiames Caire

57, La Cañada

Angelo Chavez

41, San Jose

Rita Clausen

92

Ed Pearl

88, Los Angeles

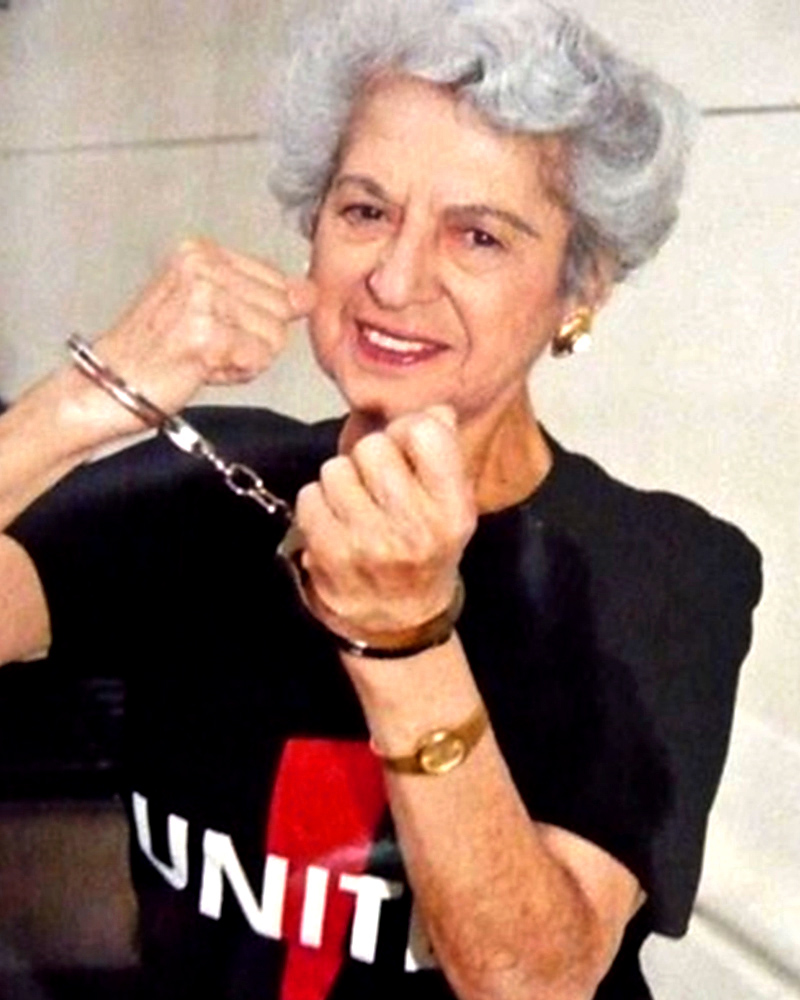

Anita Schiller

94, San Diego

Francisco Valdovinos

58, Mecca

Claudine Pearson Luppi

92, Sherman Oaks

Emilia Ibarra

59, Coachella

Nylo Corado

52, Los Angeles

Patricia Jewel Lopes

85, Modesto

Saludacion “Sally” Solon Fontanilla

51, Kentfield

Alberto Reyes and Fernando Reyes Sr.

84 and 60, Vallejo

Julia Alexander

81, Upland

Richard Ellwood

81, Glendale

Deborah Lynn Aguilar

60, Salinas

David Iribarne

47, Sacramento

Theodore Granstedt

60, Santa Clara County

Sally Lara

62, Redlands

Allen Garfield

80, Los Angeles

Ray Hylton

67, Victorville

Erane Marie Garrett

99, Sonoma

Maria Teresa Banson

62, Huntington Park

Deborah Elizabeth Gallagher

96, Sacramento

Arthur Montoya II

70, Indio

Vivian Anne Fierro

58, Commerce

Leah Bernstein

99, Woodland Hills

Jessie Garibaldo

55, Harbor City

Richard Geoffrey Salmon

68, Lindsay

Roger Santicruz

71, San Jose

Phil Specter

81, Stockton

George Shark Chou Chin

80, Davis

Bruce Barack

79, Los Angeles

Walter White

95, Rancho Mirage

Randy Giang Ta

66, San Jose

Rosaleigh George

97, Monterey

Carmella Cristofaro

88, Mission Viejo

Dena Louise Connelly

64, Santa Monica

Joseph Fierroz

64, San Fernando

Rosemary Rushka

89, San Mateo

Edwin Wall

97, Lodi

Sandra Blum

80, Encino

Donald Sperling

85, Sacramento

Jack Ohringer

75, North Hollywood

Jimmy Lee

48, Orange

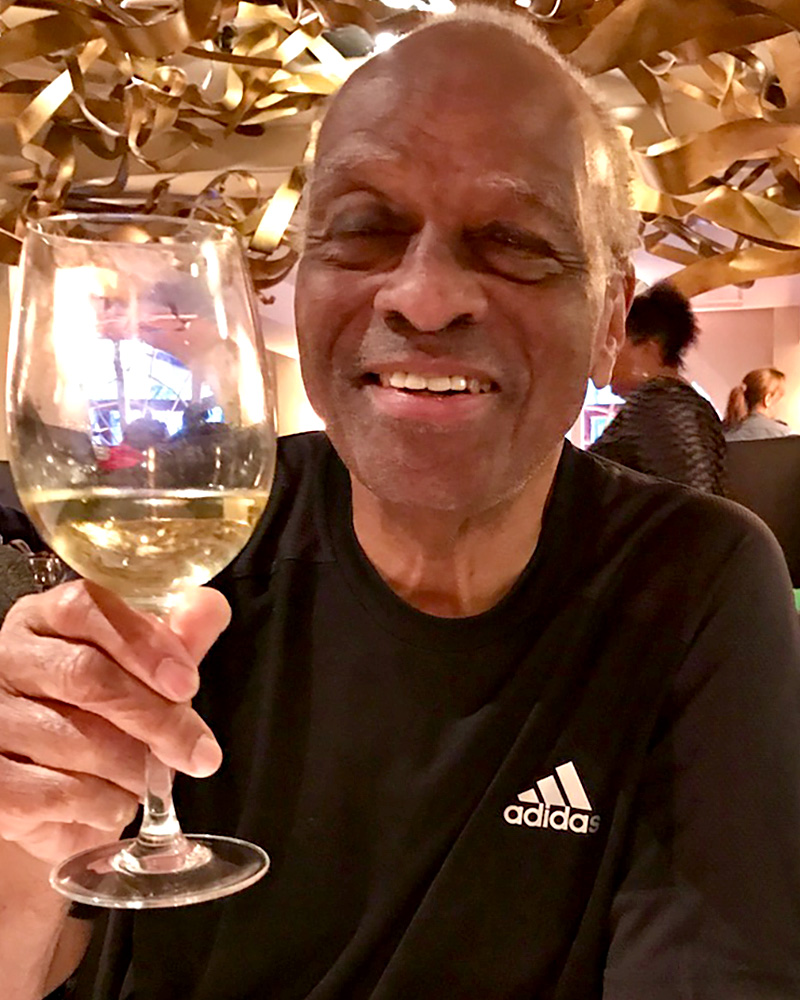

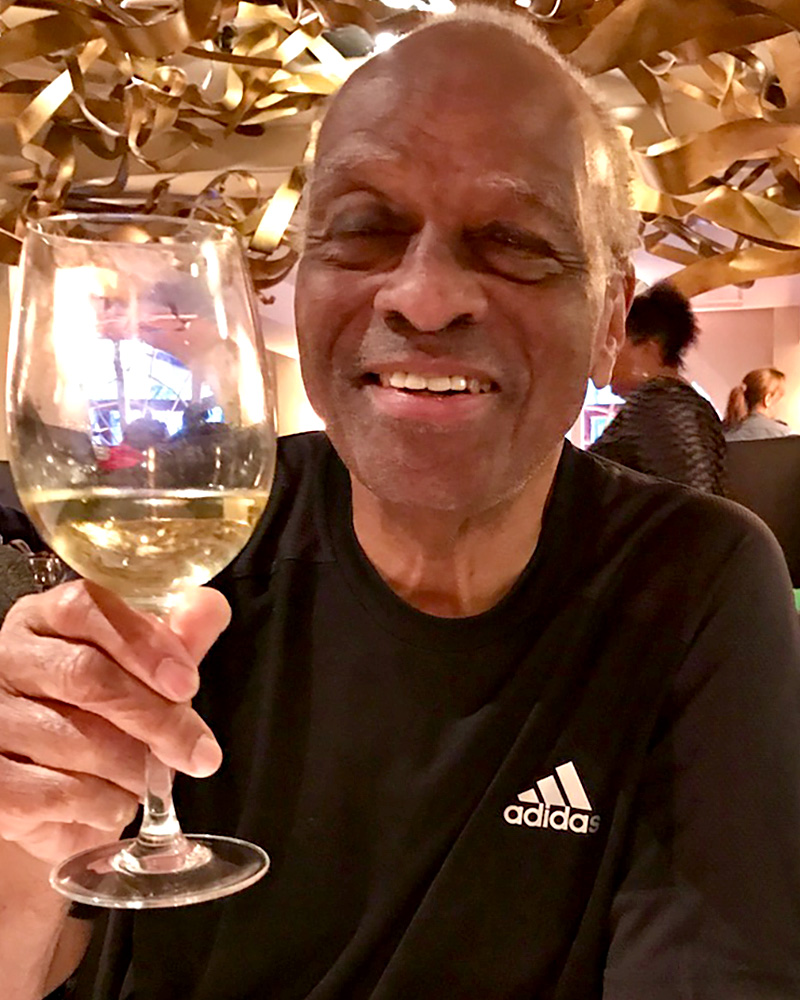

Arnie Robinson

72, San Diego

Gregory Everett

58, Los Angeles

Becky Blair

64, Santa Rosa

Celia Marcos

61, Hollywood

Donald Lackowski

86, Redondo Beach

Jeffrey Ghazarian

34, Glendora

Antonia ‘Toni’ Sisemore

72, Esparto

Eric Oshiro and Betty Oshiro

61 and 89, La Mirada and Paramount

Camille Ellington

66, Marina del Rey

Jeanne Mary Roche

82, San Rafael

Julie Bennett

88, Hollywood

James Lanier Craig

64, Santa Paula

Victor “DJ V-Funk” Martinez

36, Porterville

Jay Calhoun

58, Bakersfield

Ricardo Saldana

77, Glendale

Mario Aranda Sr.

79, San Francisco

Leticia Chavez Godinez

75, El Centro

Raul Miramontes and Adeline Miramontes

90 and 83, San Jose

Eliseo del Rosario Moya

75, West Covina

Larry Lerner

71, Van Nuys

Edwin Echaluce

70, San Jose

Allen Daviau

77, Woodland Hills

Gaspár Gómez

51, Pacoima

Dora Padilla

86, Alhambra

Richard Tillson

85, Elk Grove

Lynn Naibert

83, San Diego

Ressie Cameron

87, Gilroy

Cynthia Brasil

64, Modesto

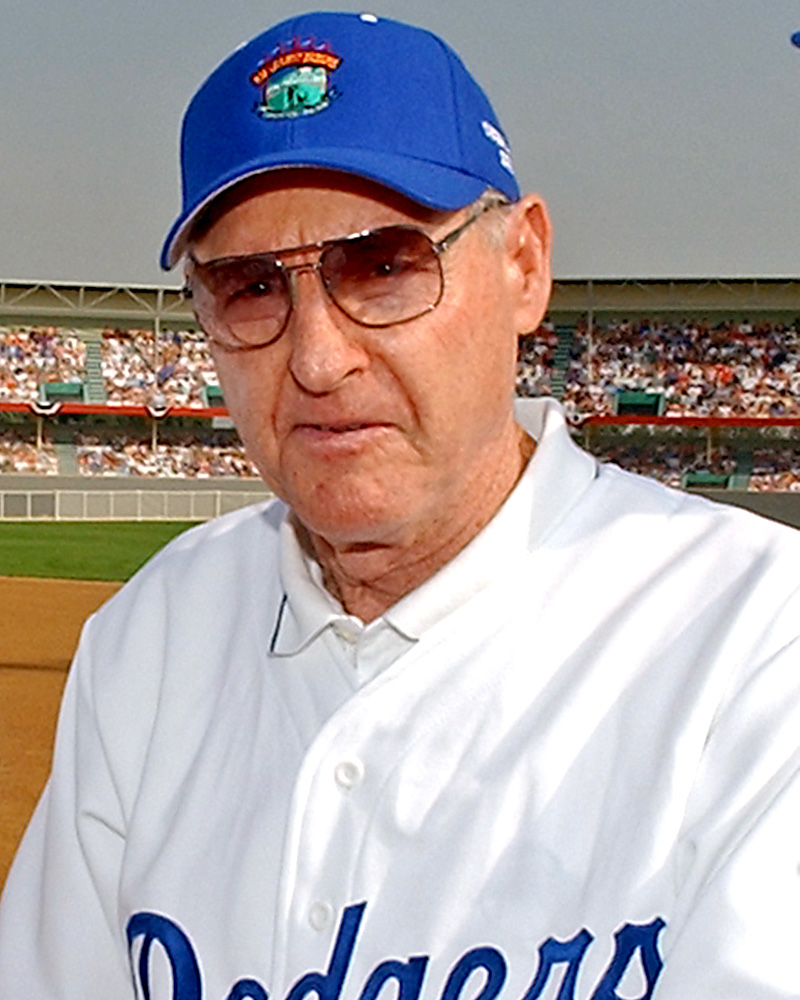

Jay Johnstone

74, Granada Hills

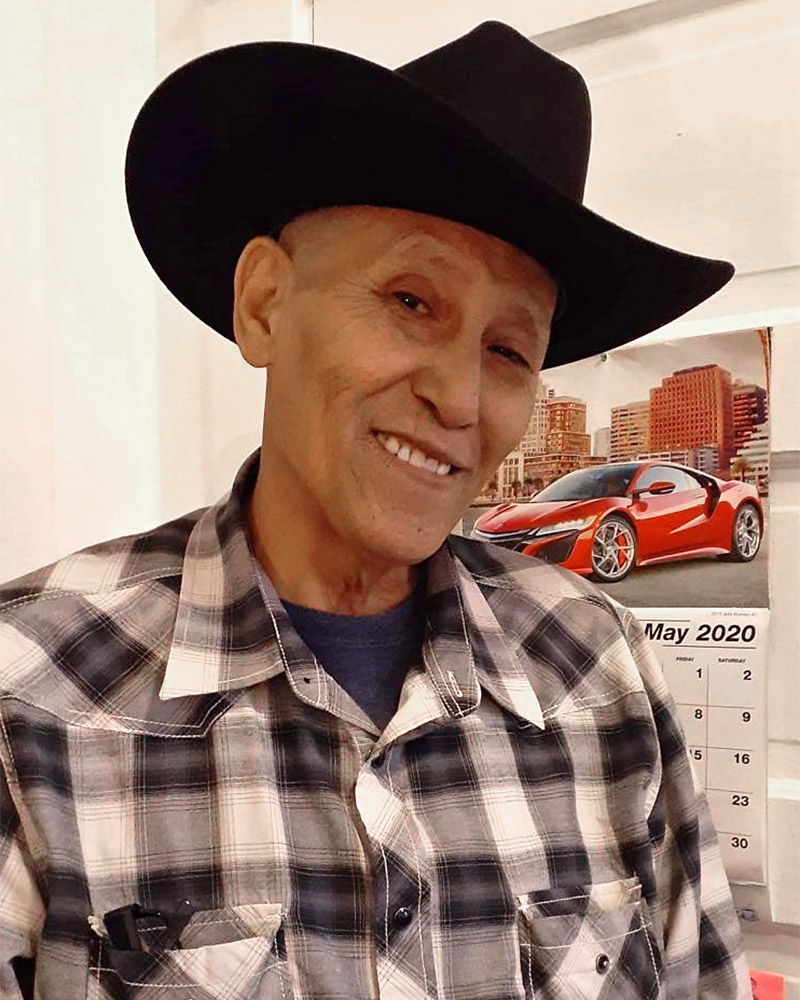

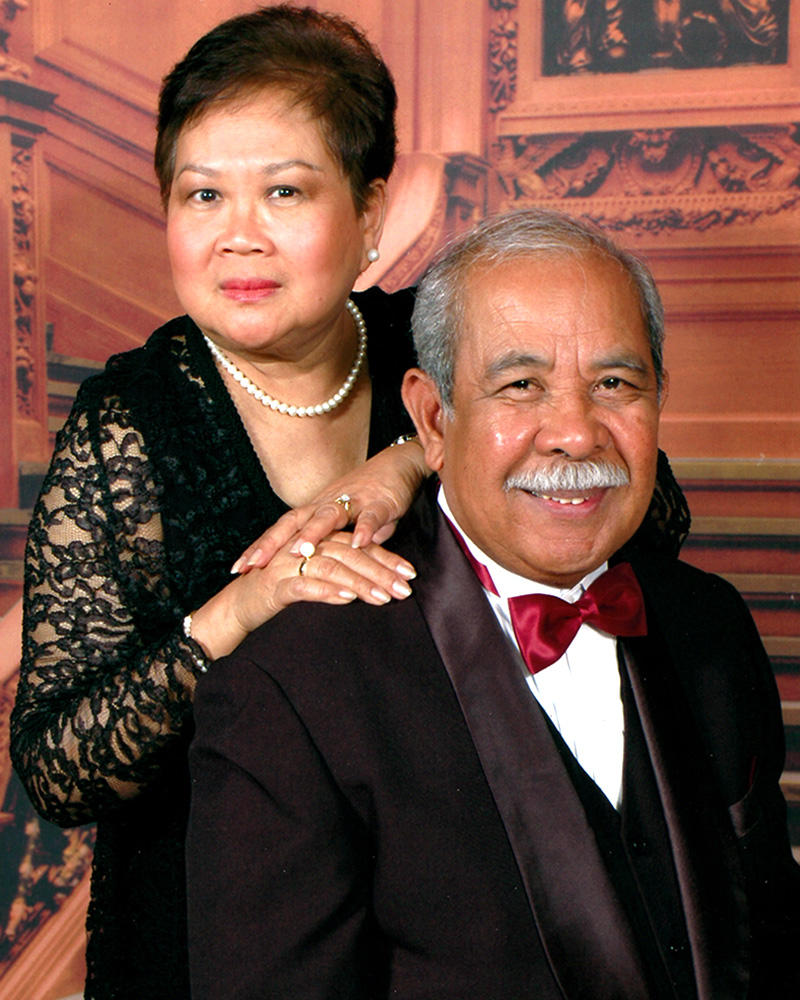

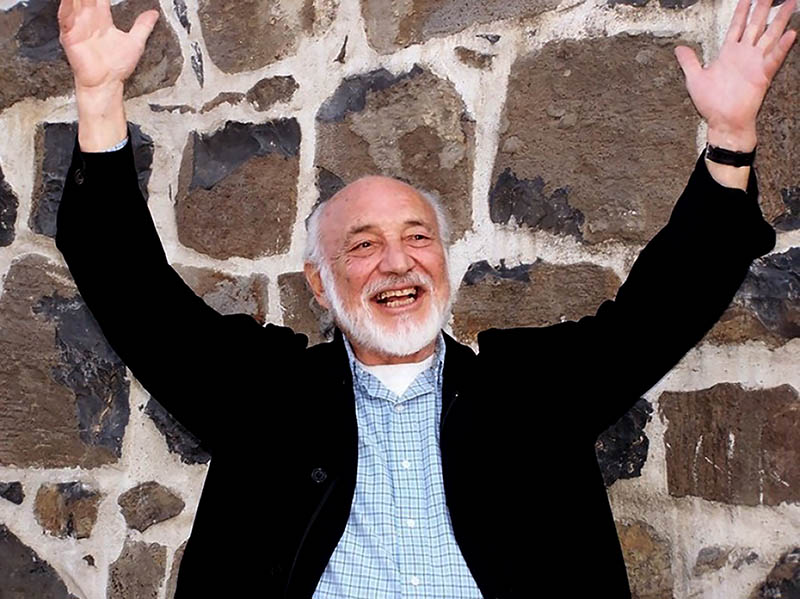

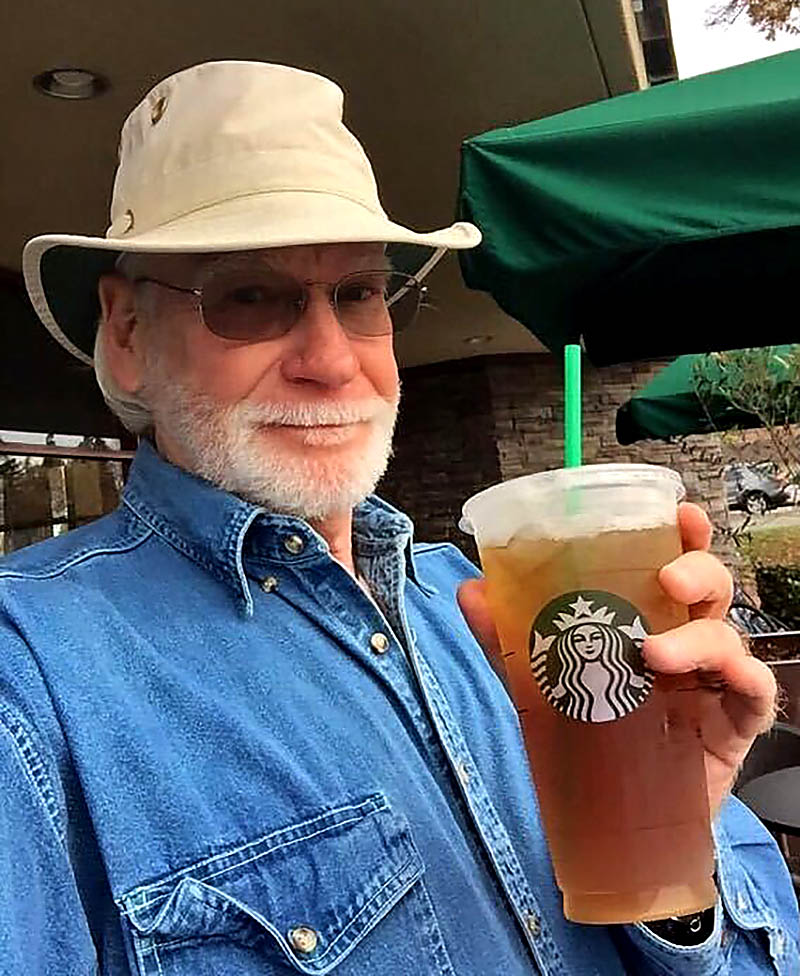

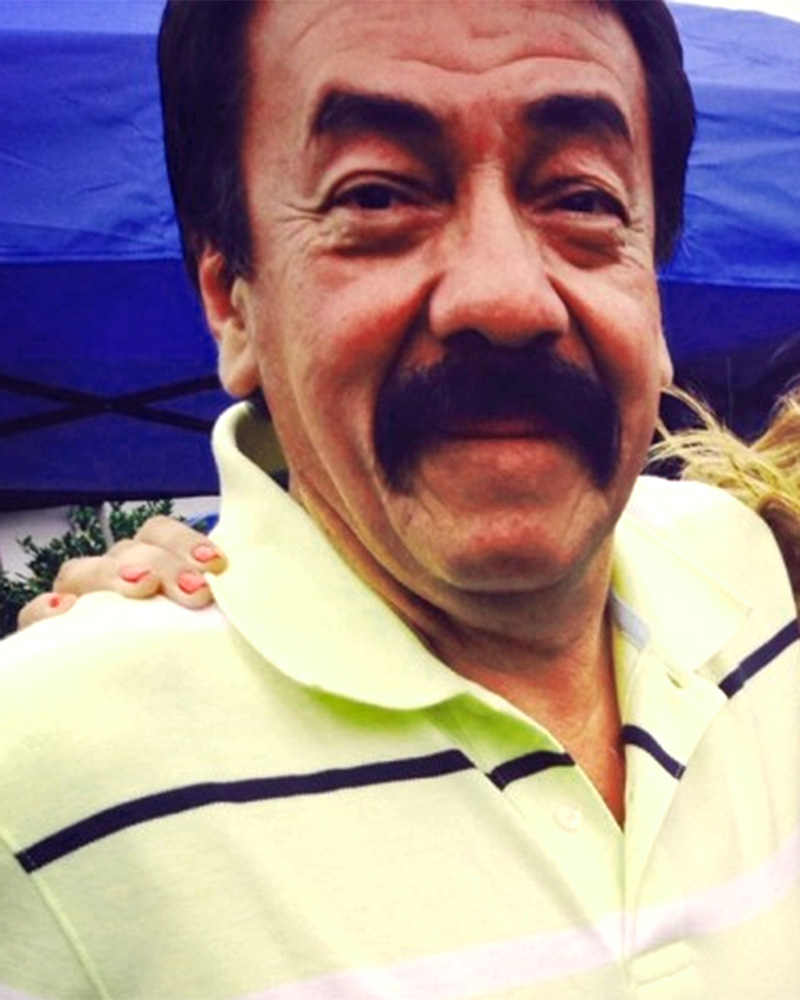

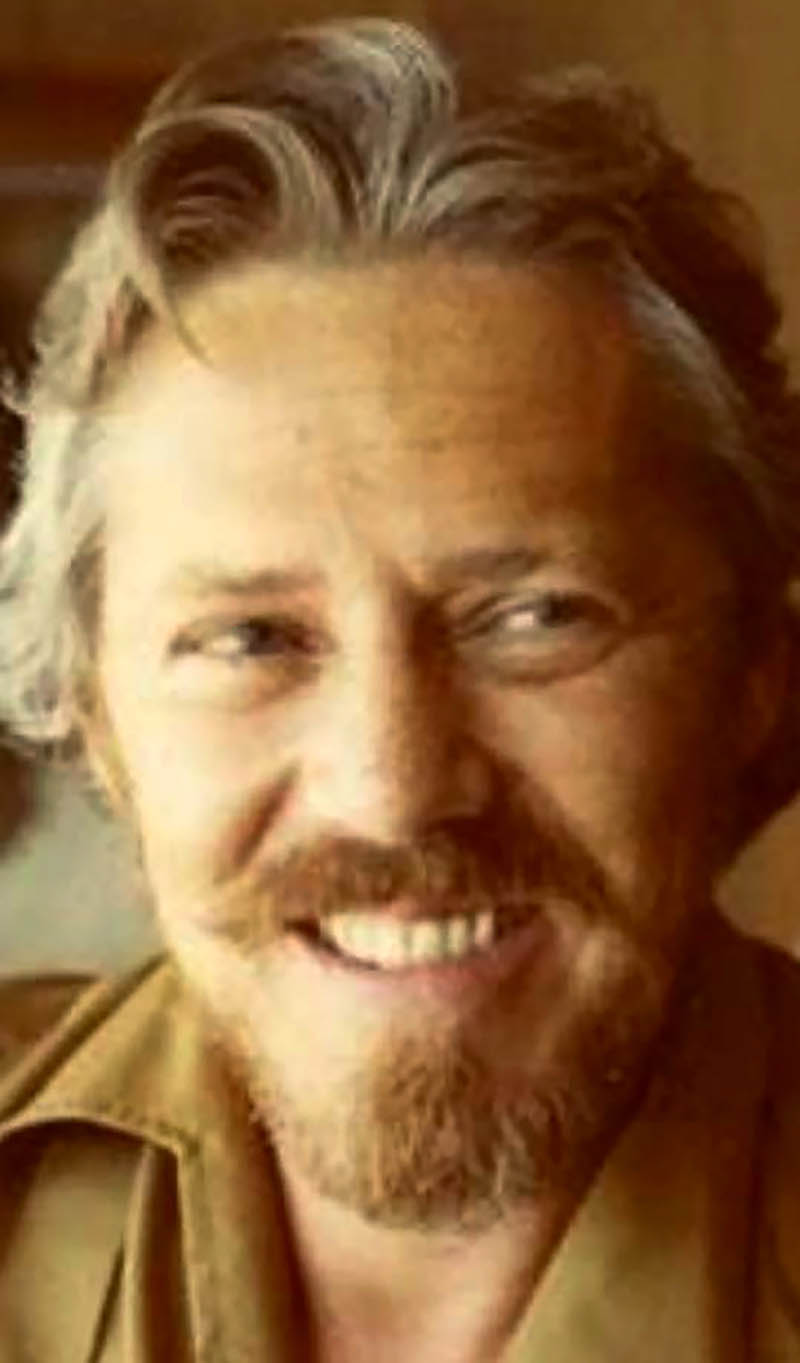

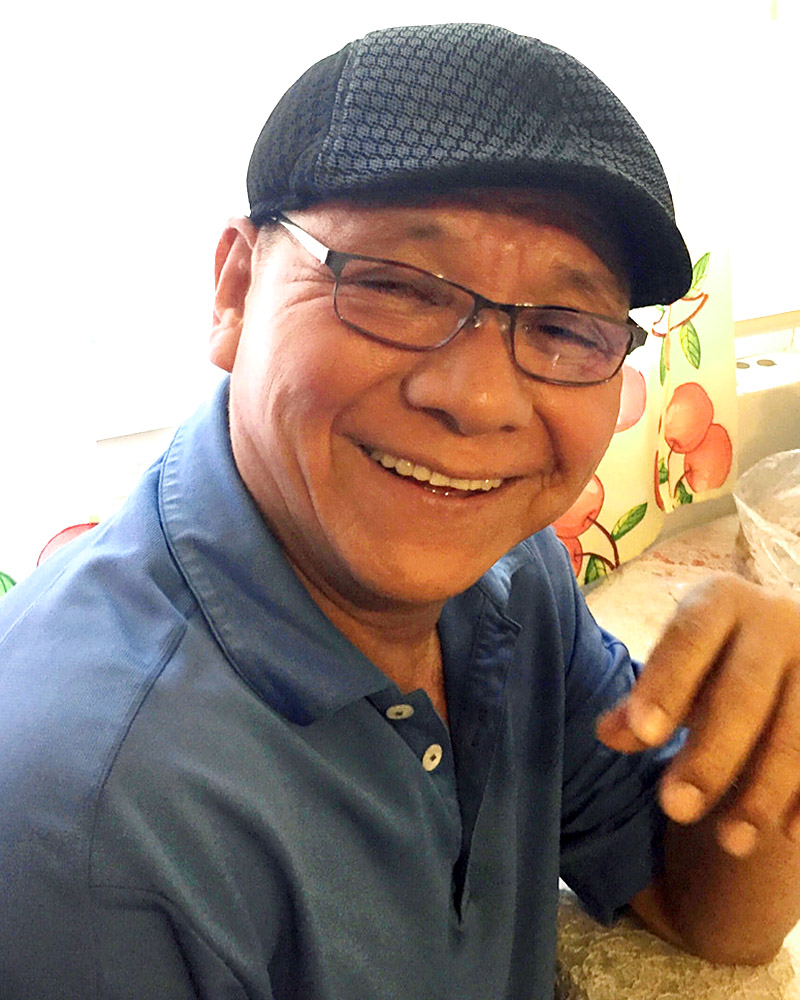

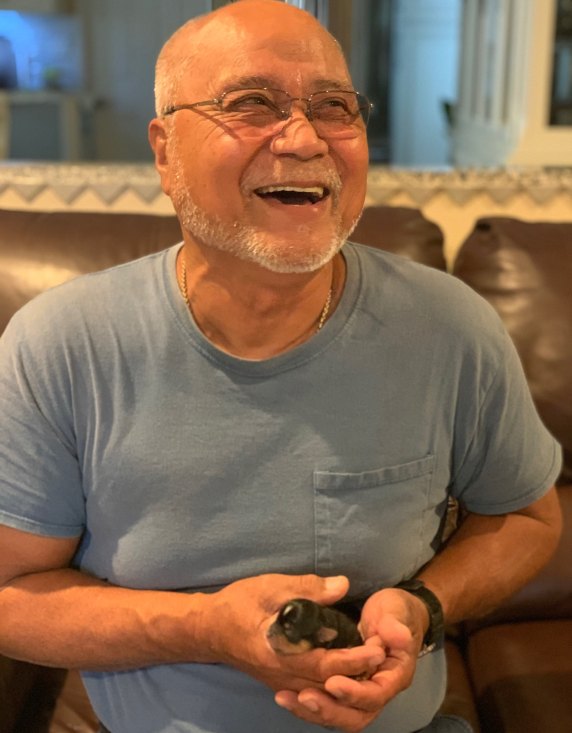

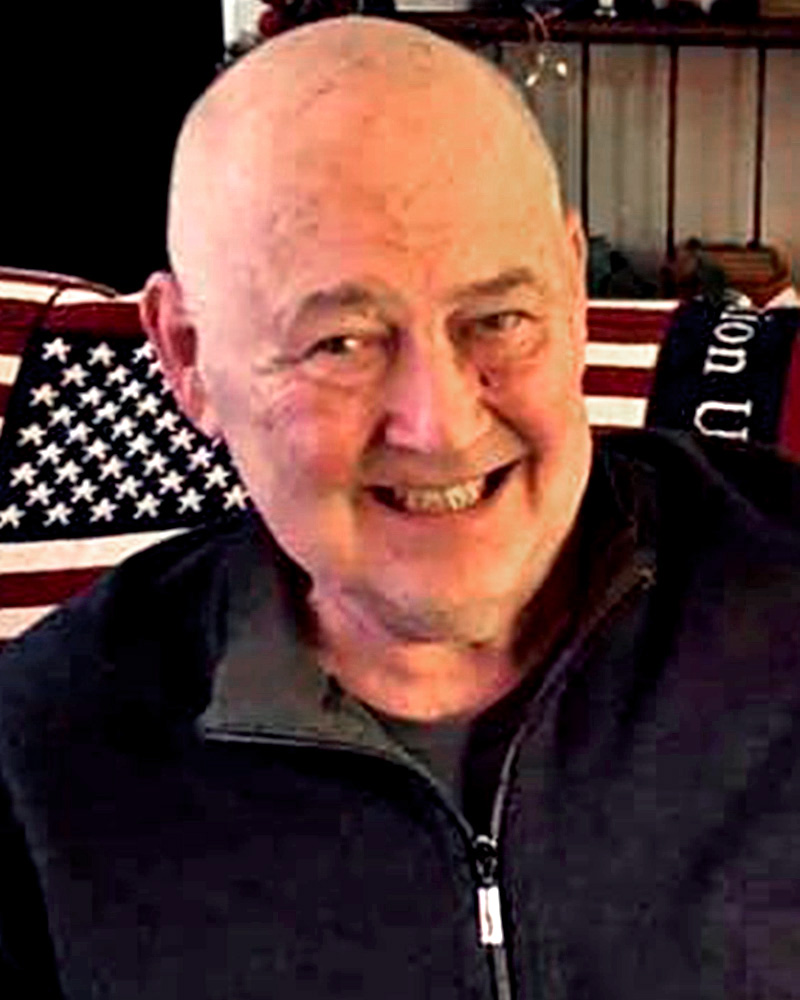

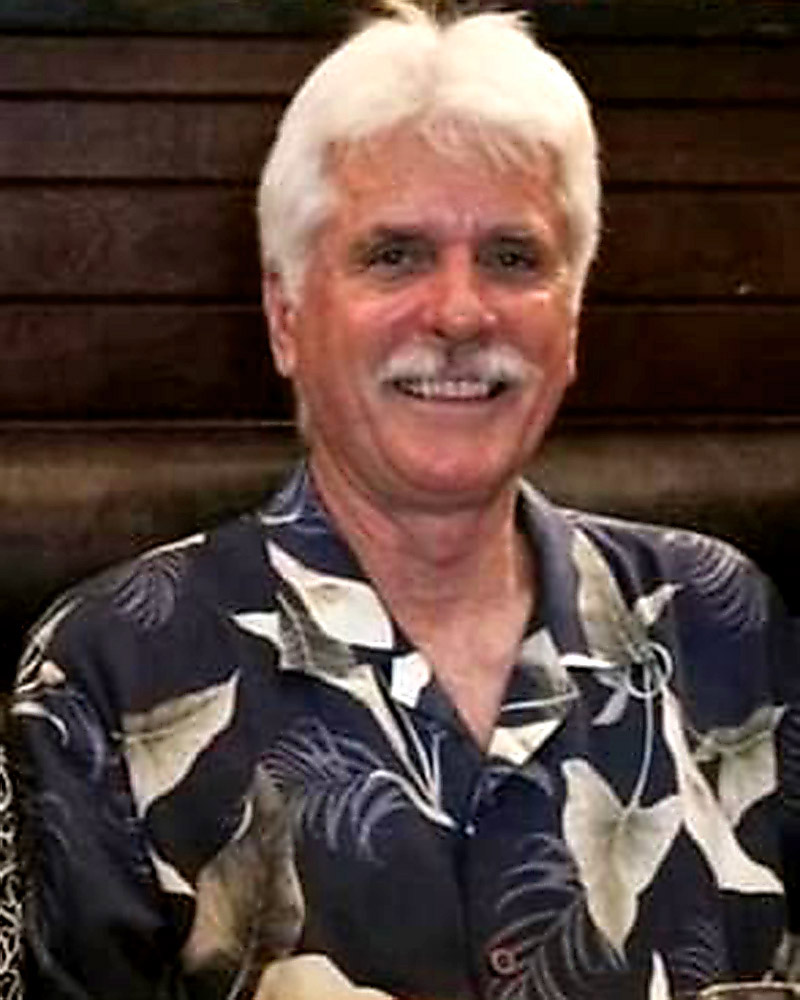

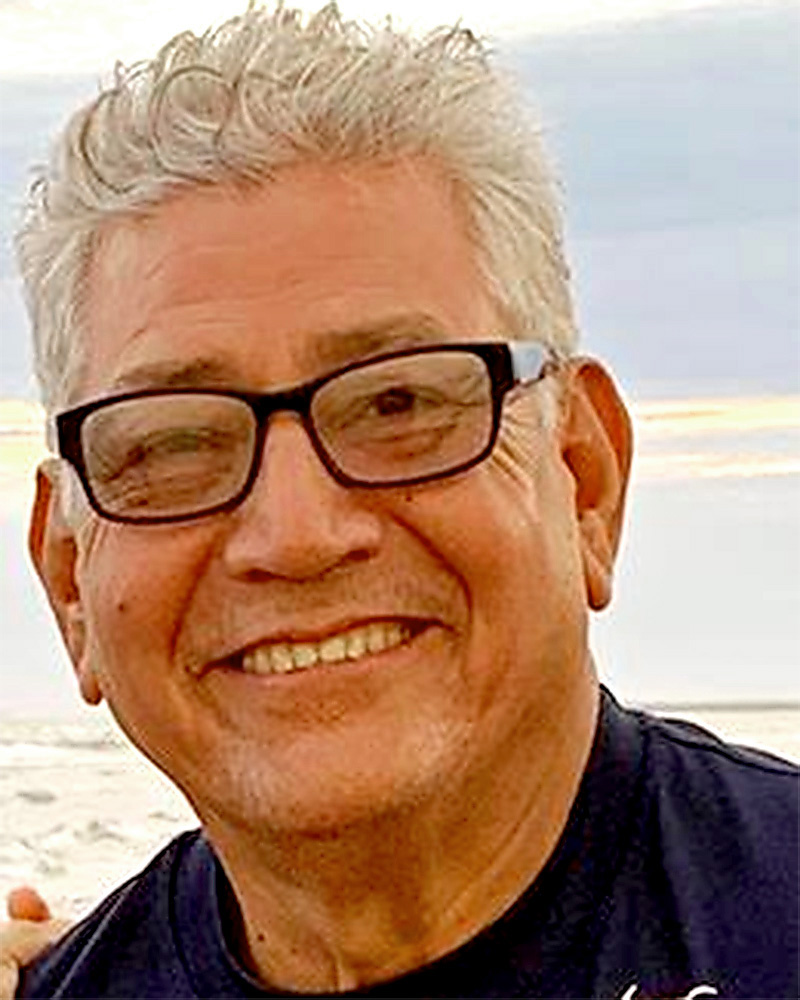

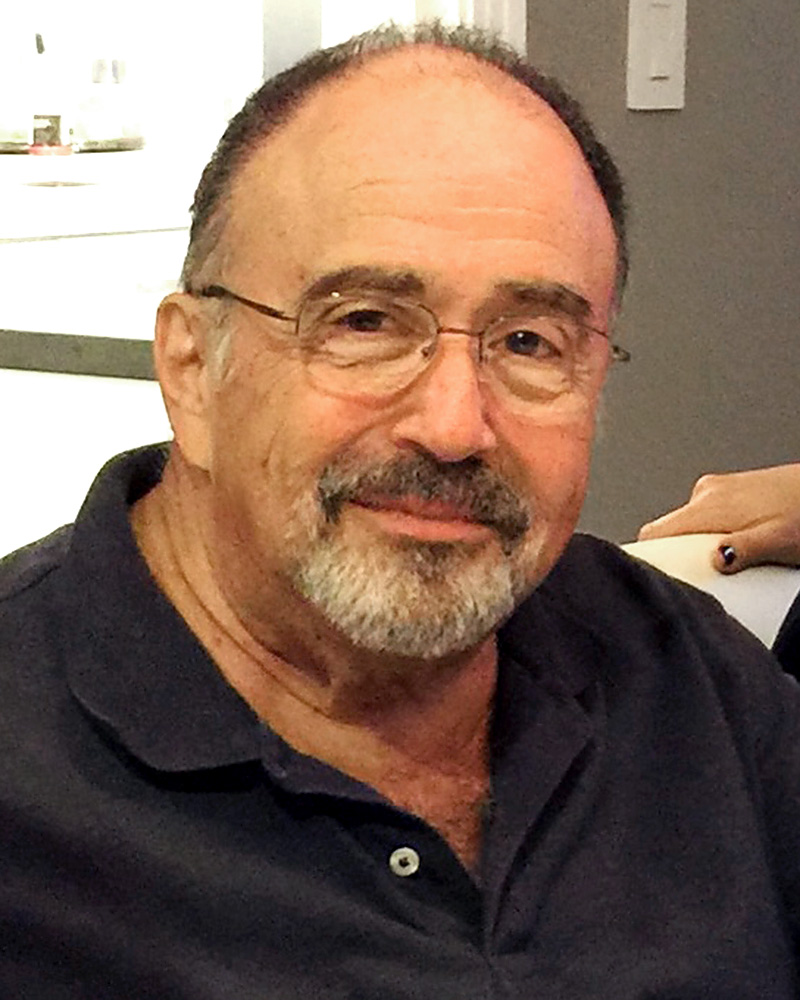

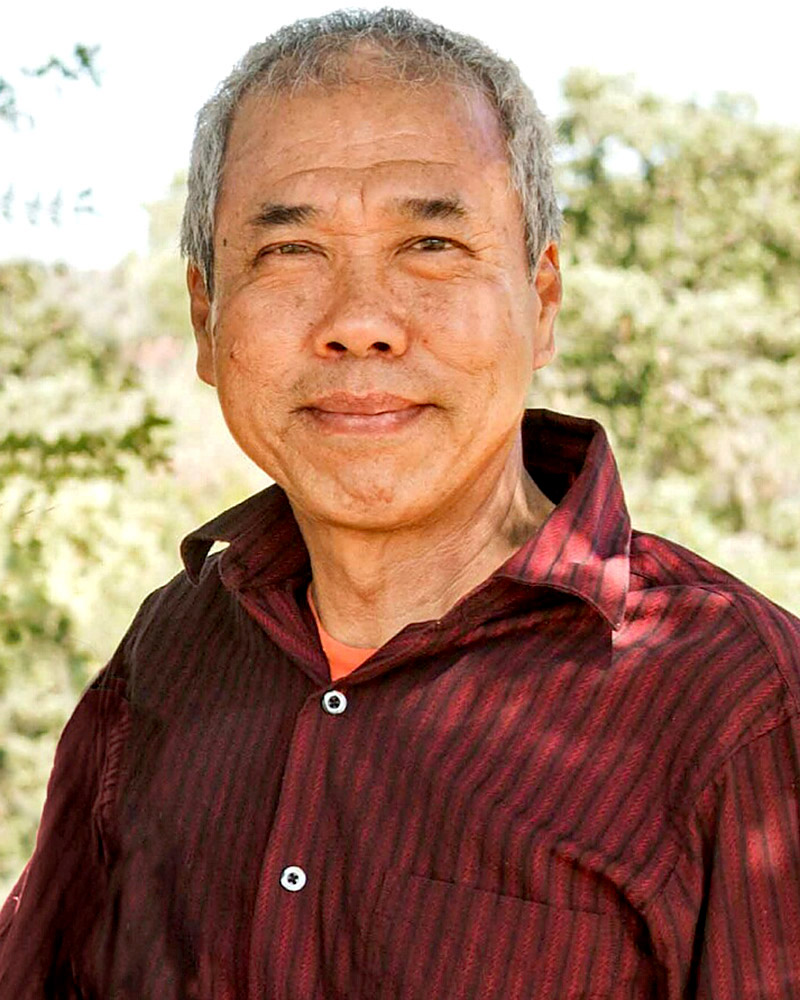

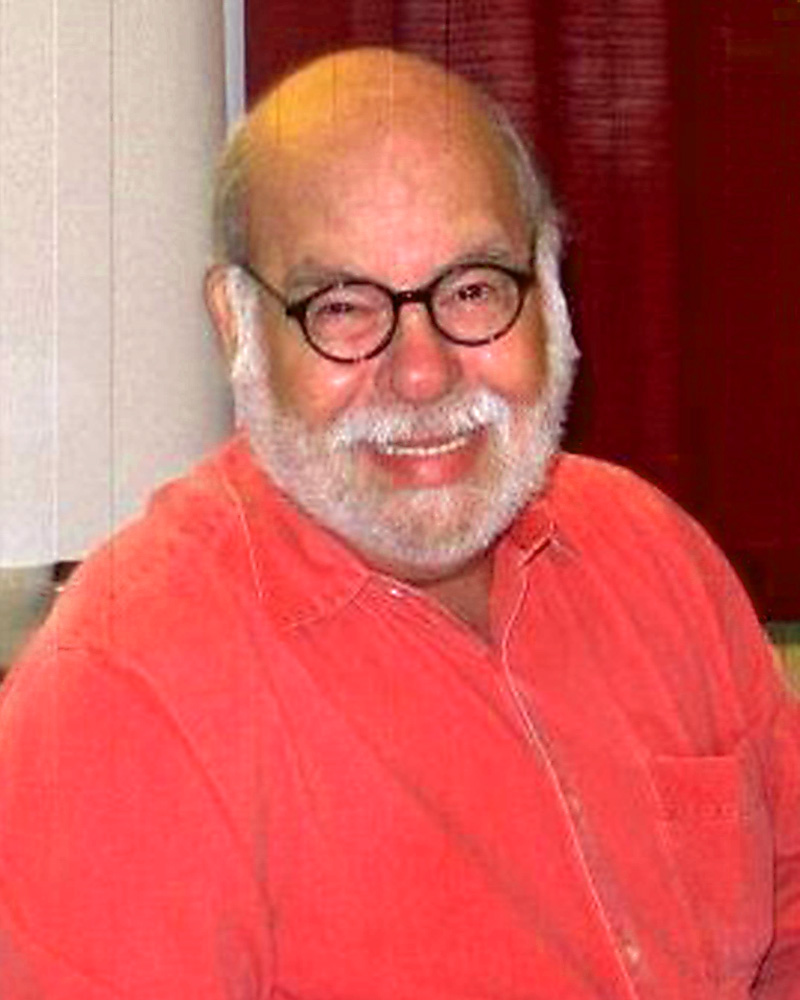

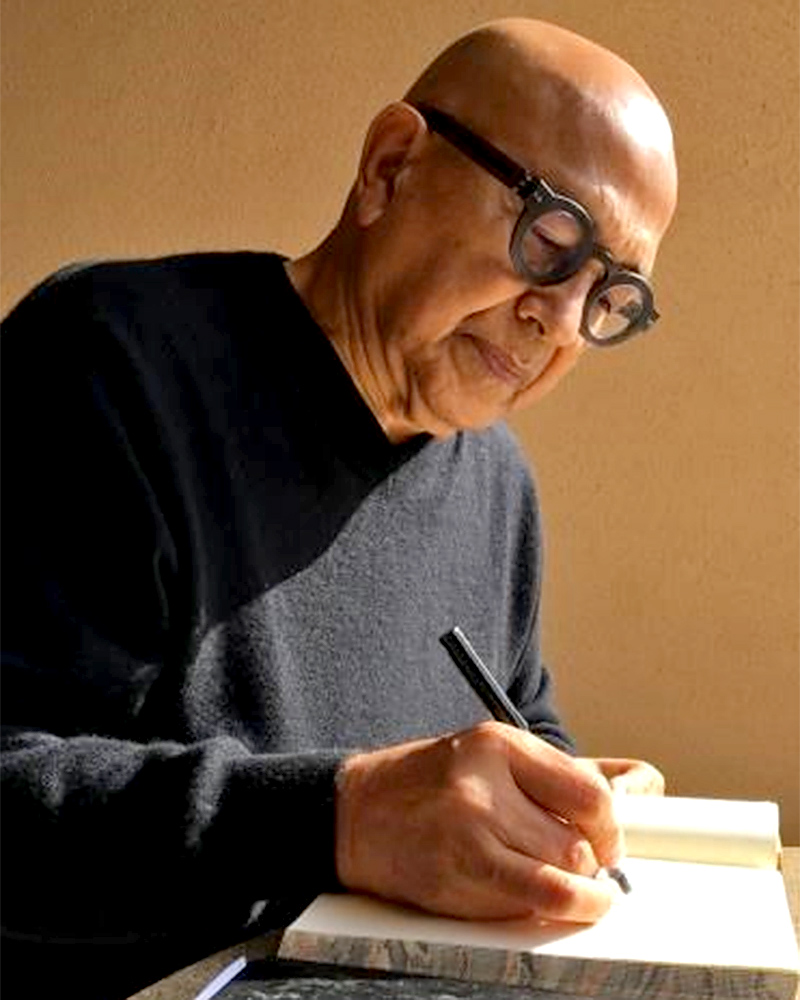

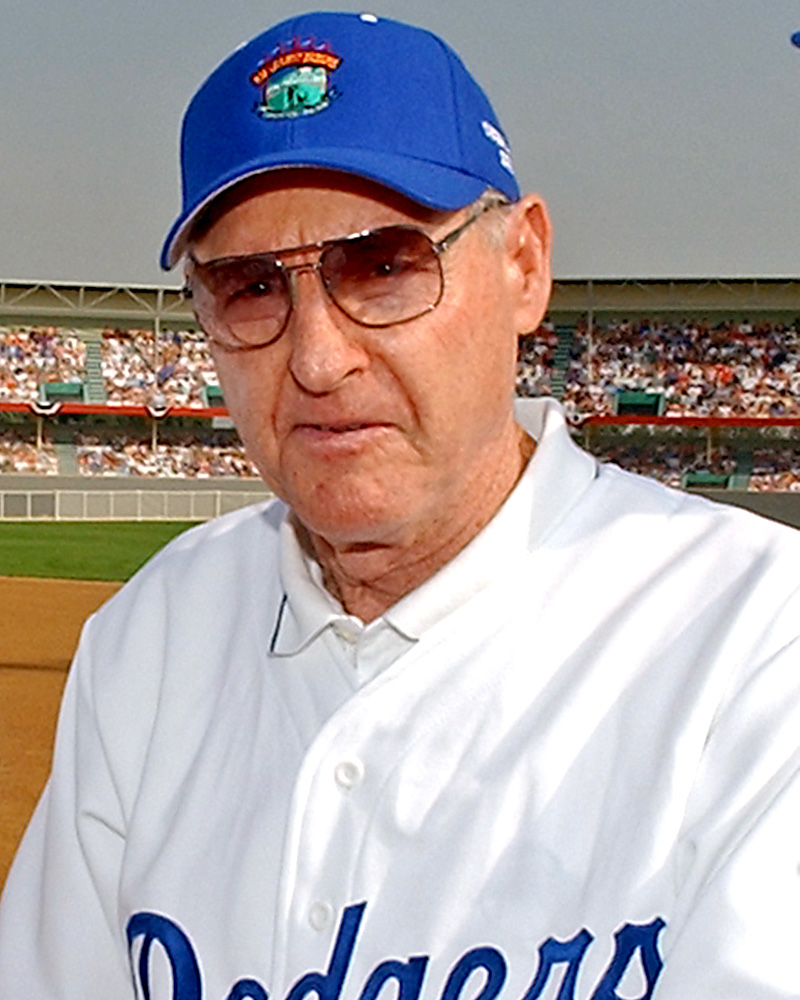

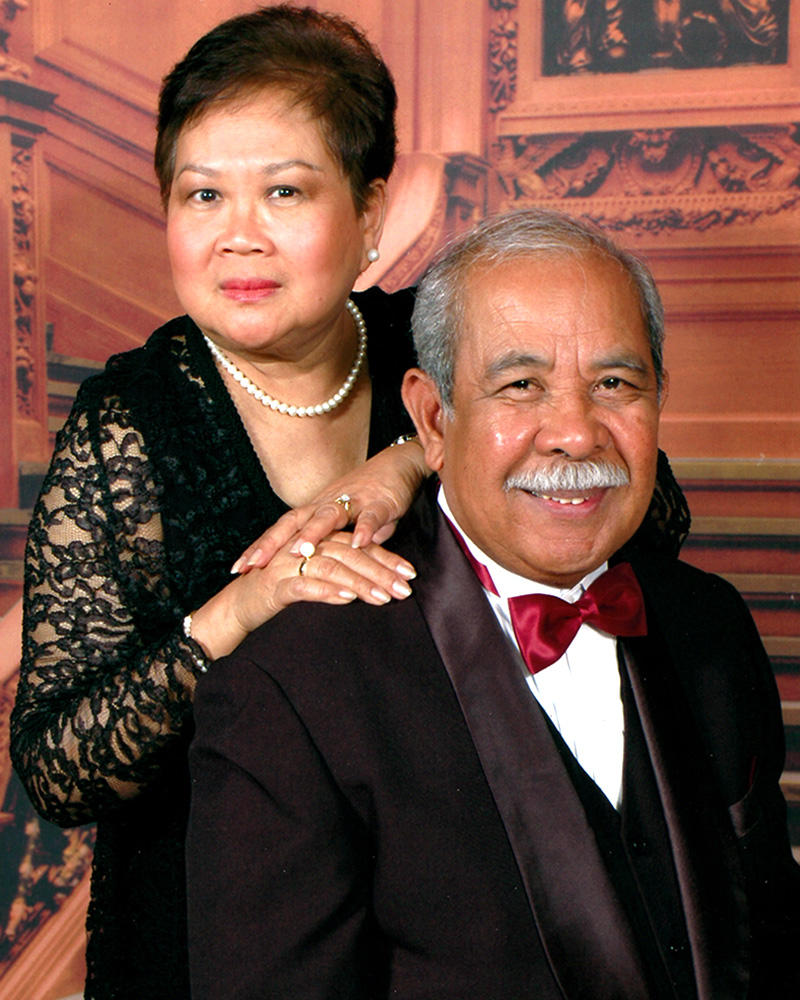

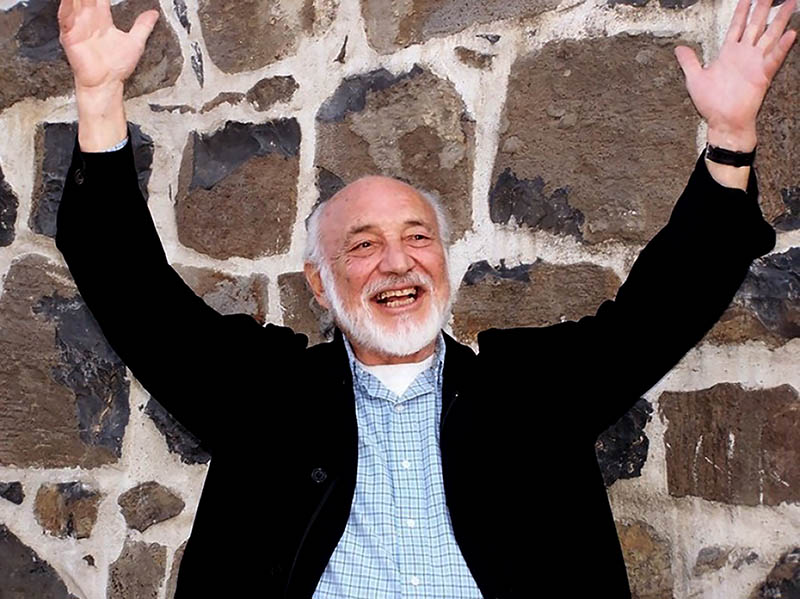

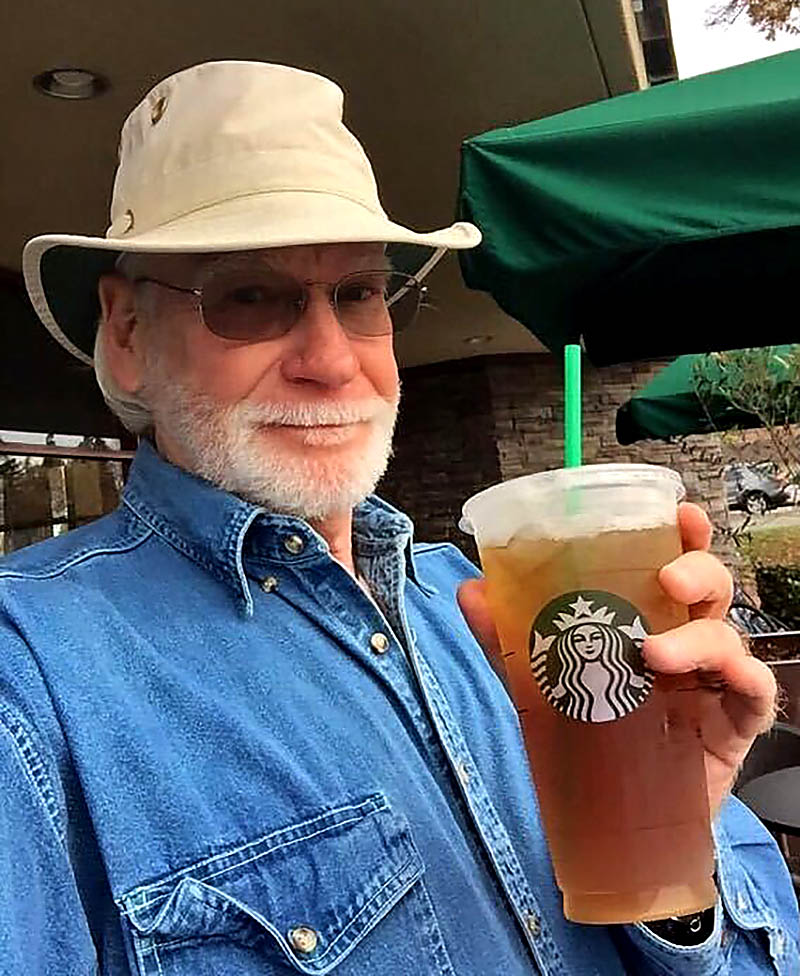

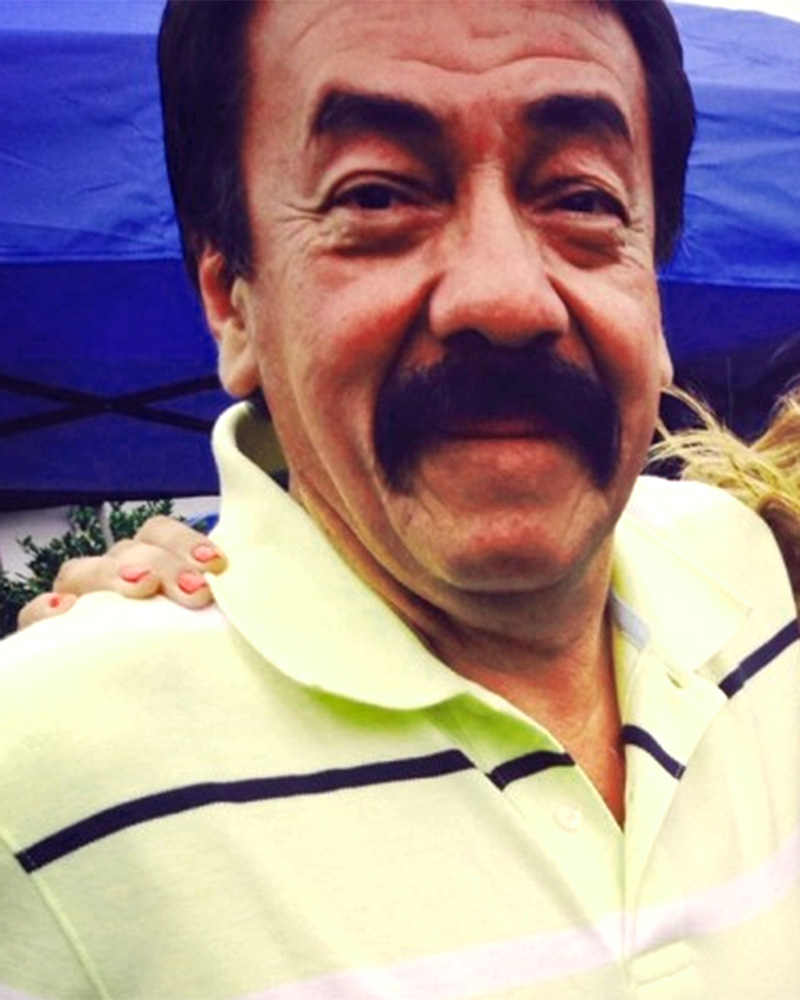

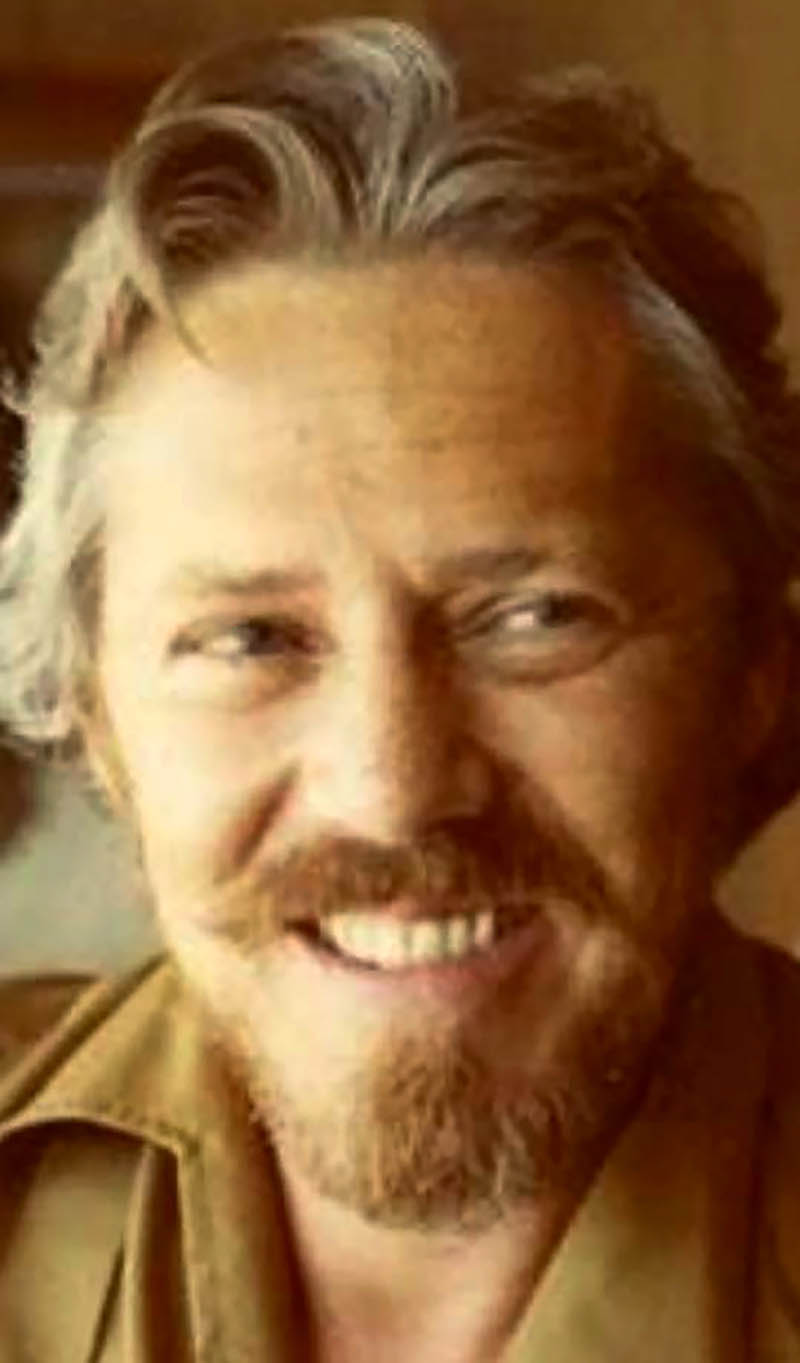

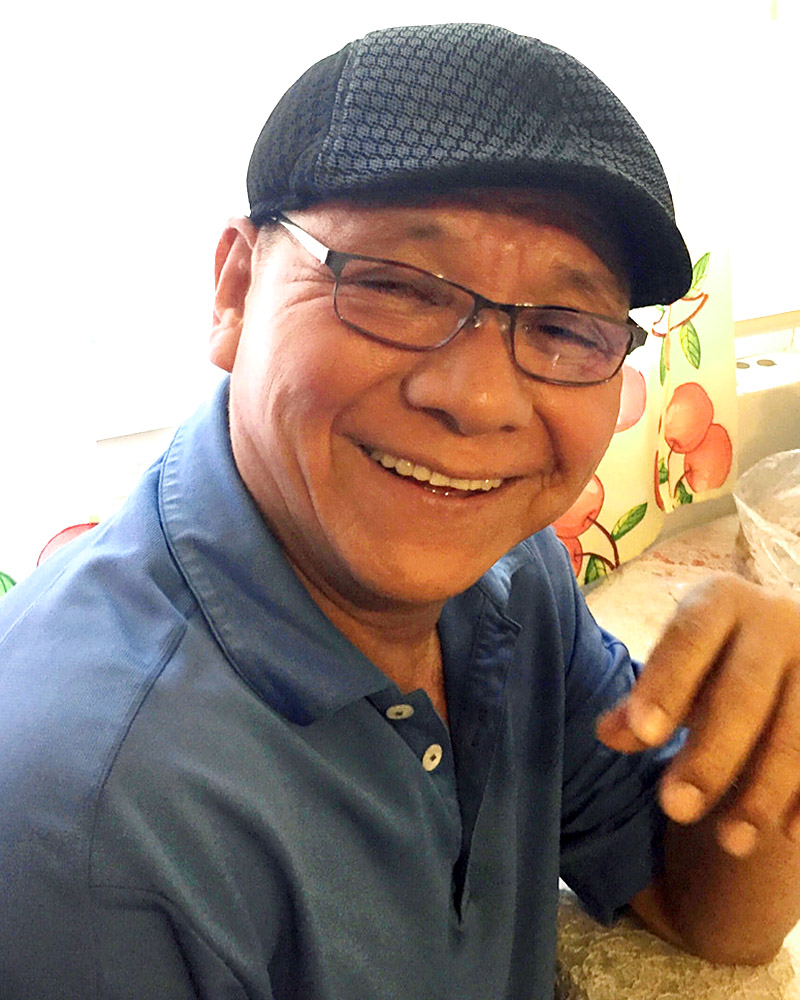

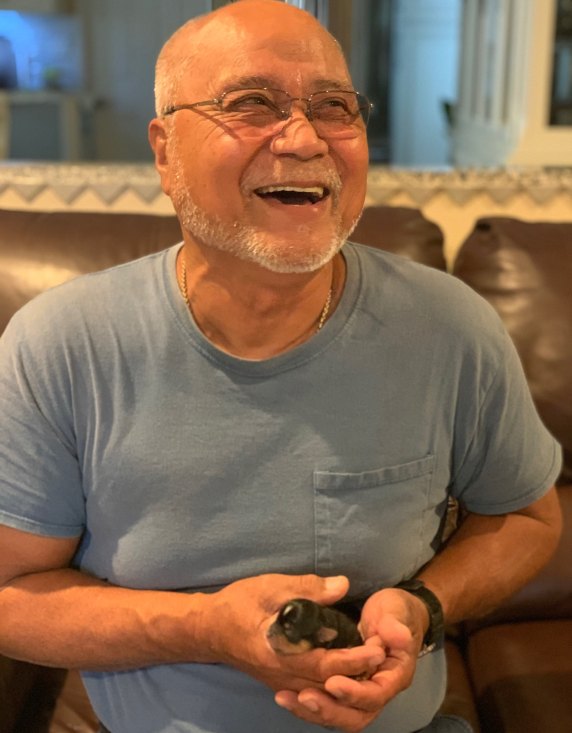

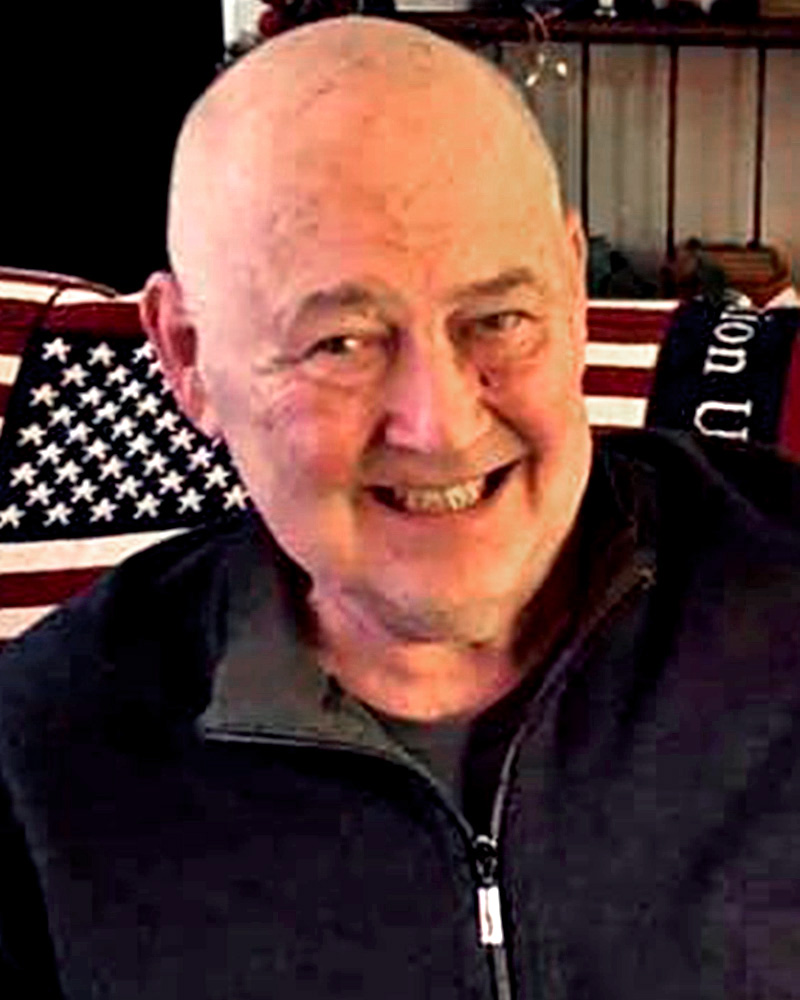

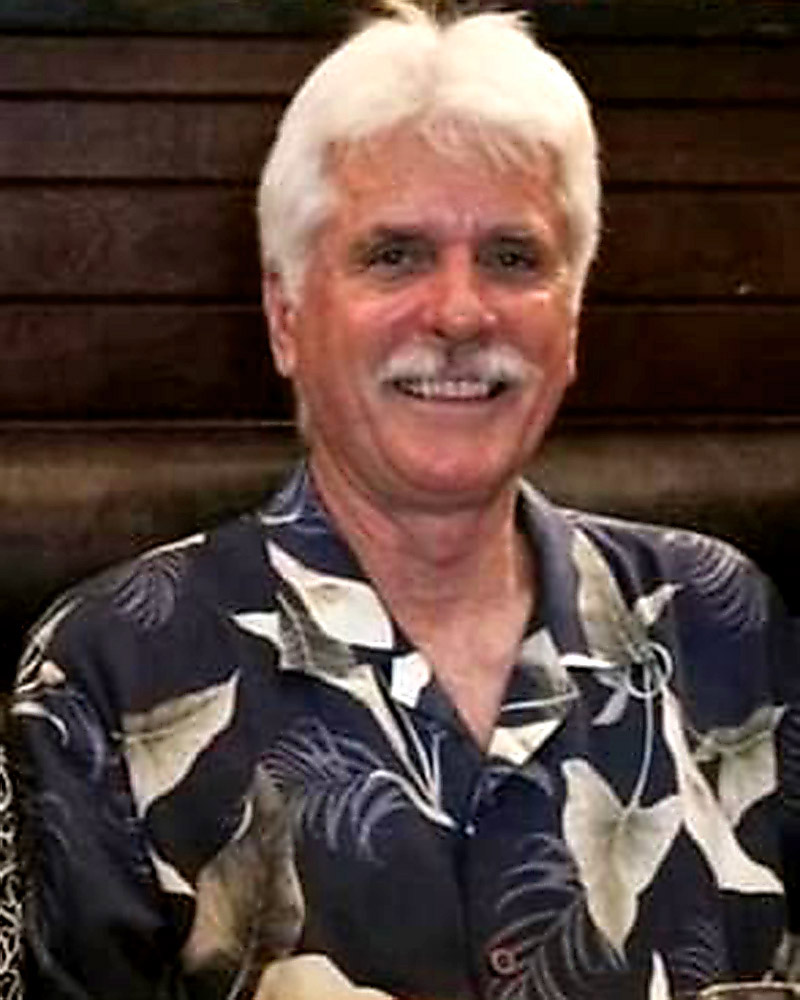

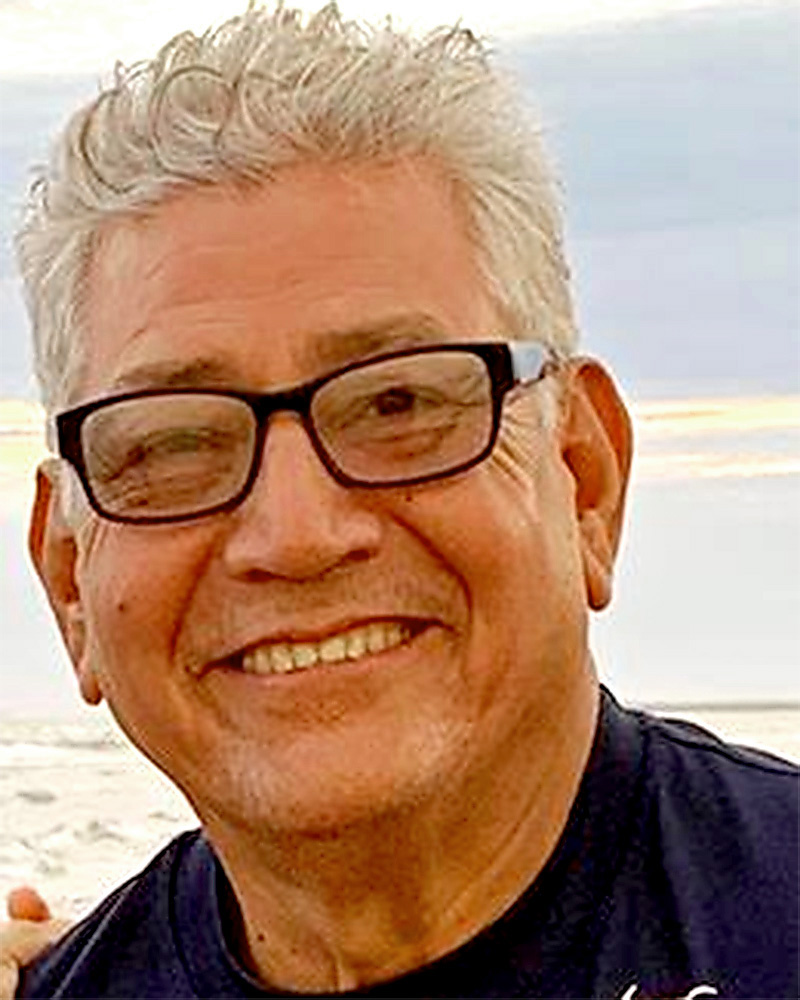

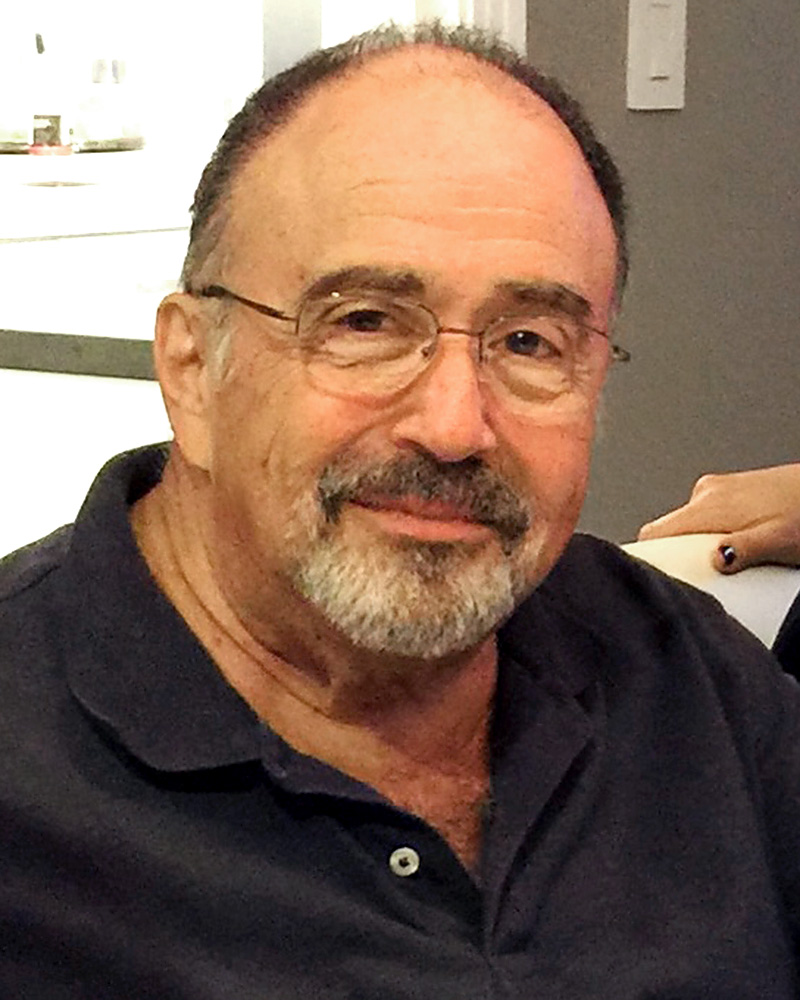

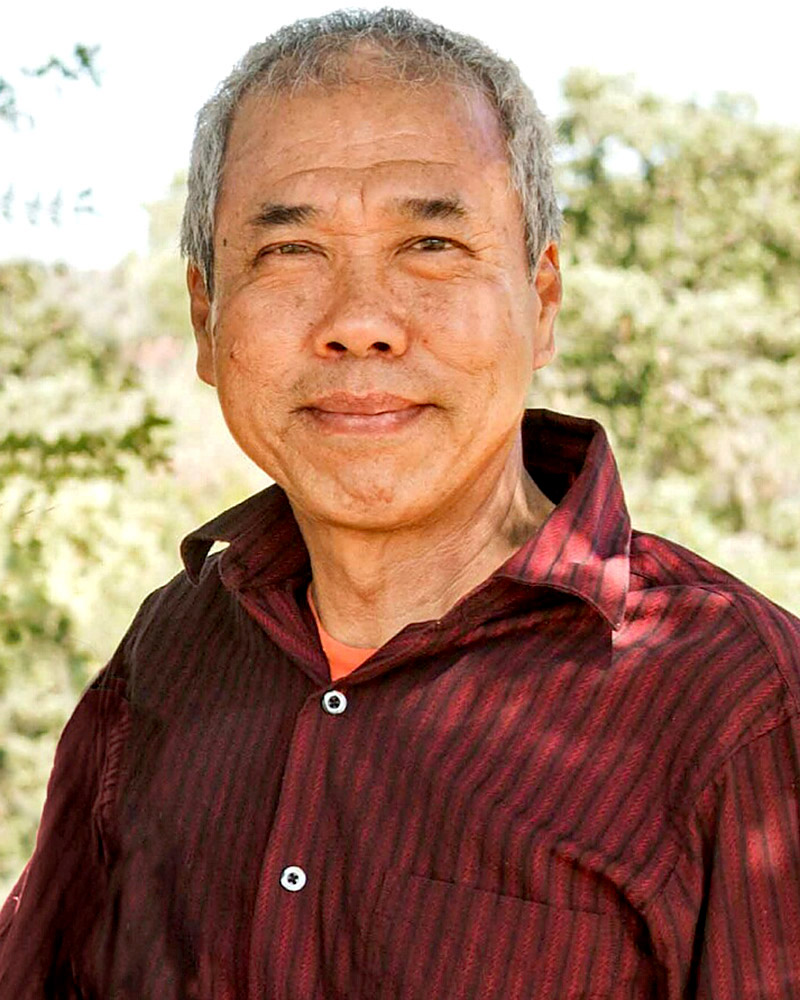

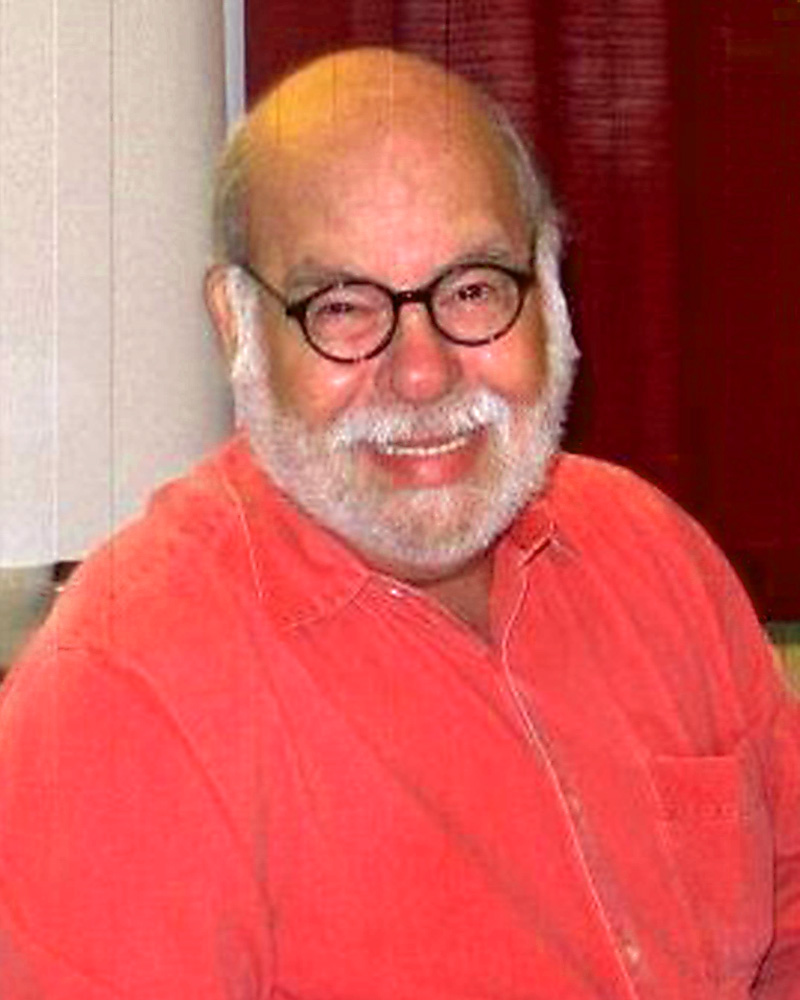

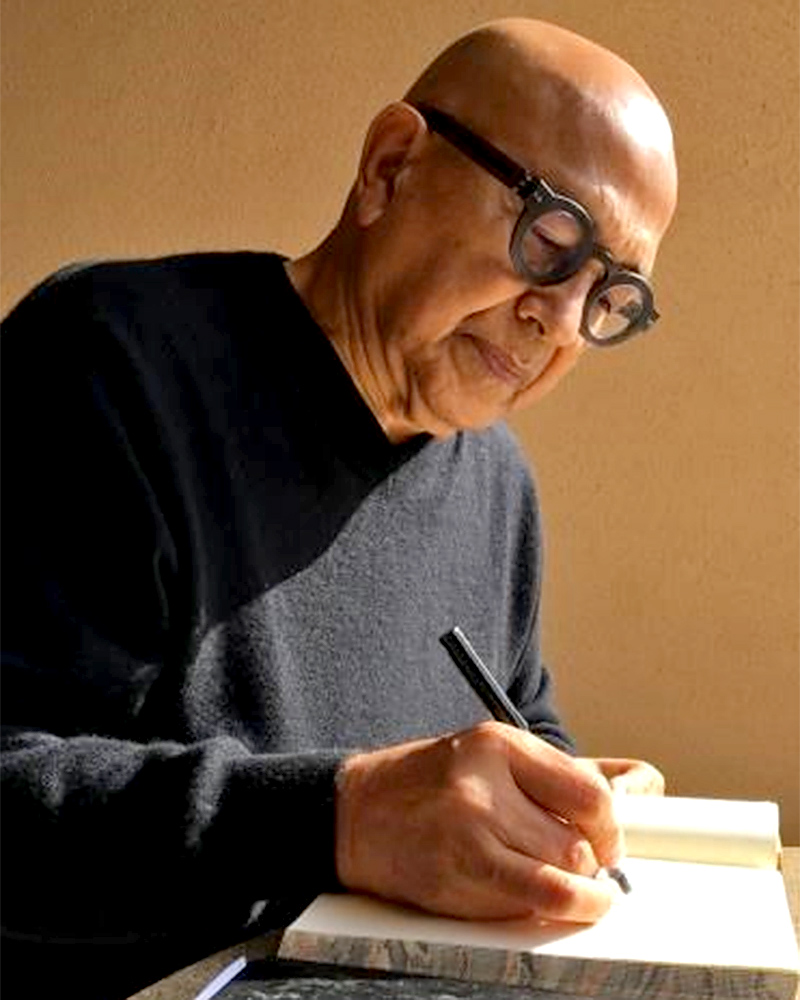

Michael Ayala

66, Sonora

Michael Ayala retired from the California Highway Patrol in 2009 after putting in 30 years. But he never really stopped working. He just shifted his focus to his church and local civic groups around his Sonora home, filling needs, lending his time, getting things done.

“He had the heart and the talent and the personality to meet just about any demand,” said his daughter Erin Natter. “His life was defined by service. He was so charismatic that people just gravitated toward him. And he embraced that.”

Born in Burlingame and raised in San Bruno, Ayala married his high school sweetheart Nancy in 1974 in Long Beach and joined the Highway Patrol five years later. Though that choice of vocation was made with an eye toward stability, Ayala soon realized that law enforcement was a good fit for his leadership and problem-solving skills. During his career, he served as a patrolman and sergeant, retiring as a lieutenant commander in Sonora.

Ayala then shifted gears, stepping in to be the executive director of the Tuolumne County Chamber of Commerce for three years when the organization was struggling. Ayala also was active with the Kiwanis Club and Sierra Bible Church in Sonora. Possessing a personality as big as his heart, he was known and liked by just about everyone in the small community.

“If someone needed help with bills, he’d throw a dinner,” Natter said. “If a fundraiser came along, he’d organize it. He was a high-energy guy and loved diving in to help out.”

Being a huge San Francisco Giants fan – he and Nancy and their two daughters, Erin and Heather, would drive from Modesto to Candlestick Park when they held season tickets – Ayala was thrilled to celebrate the team’s three championships during the past decade, sharing that delight with his family.

“He was a very present father,” Natter said.

Ayala was hospitalized and diagnosed with COVID-19 shortly after Thanksgiving. He died in Sonora on Dec. 6. He was 66.

In addition to his wife and daughters, he is survived by his mother, Mary; a sister, Lisa; and four grandchildren.

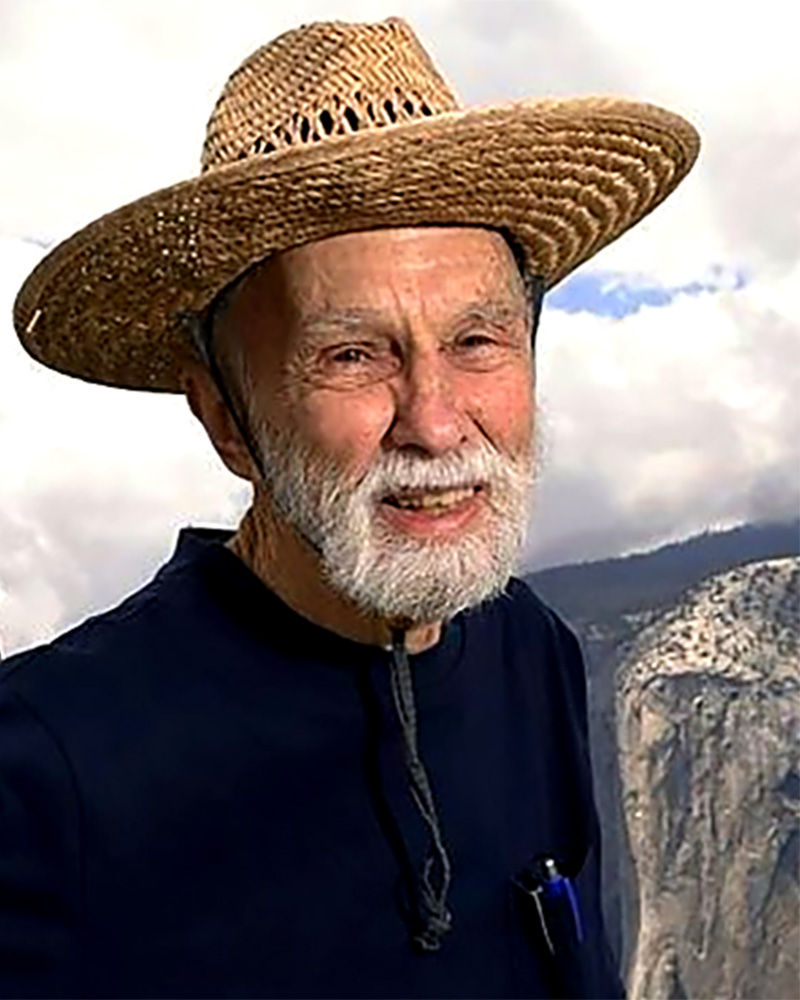

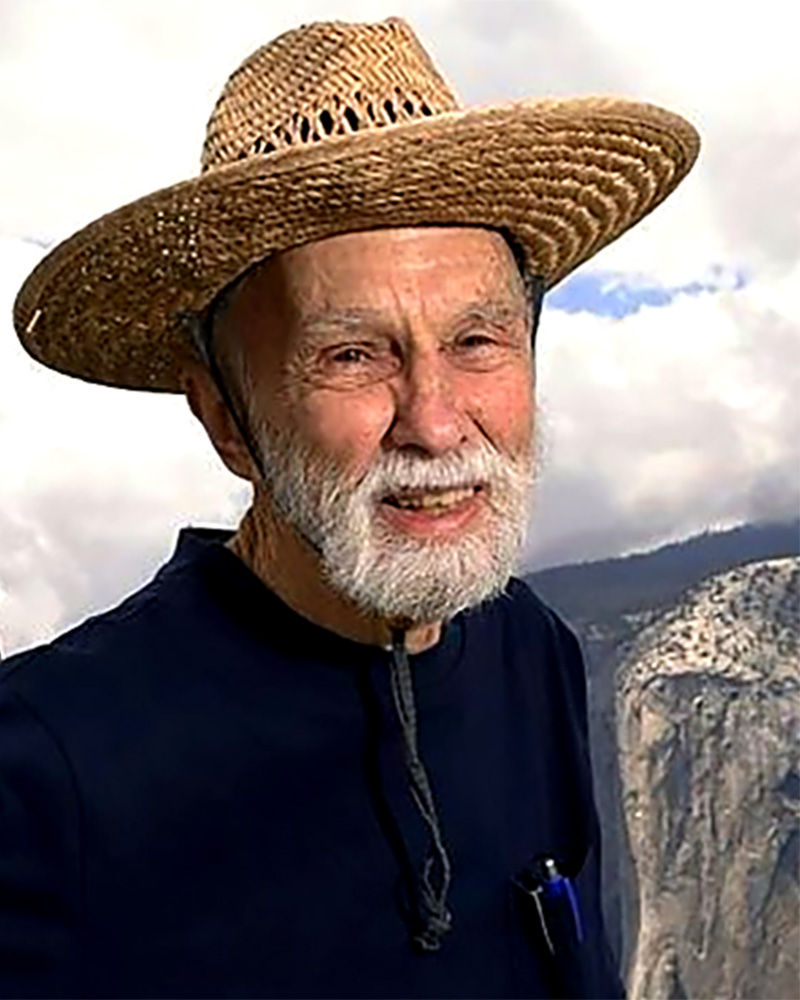

Penny Foreman

73, Clovis

The deadliest American epidemic of the 1950s was polio, which killed thousands of children and paralyzed tens of thousands more.

A Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., first-grader named Penelope A. Miller, better known in her grown-up years as Penny Foreman of Clovis, was part of the effort that defeated the disease.

As researchers searched for weapons against the virus in 1954, 6-year-old Penny and her 8-year-old brother Jim joined thousands of boys and girls in an 11-state medical trial, receiving an injection that included either the new vaccine or a placebo.

Jim stayed healthy. Penny didn't.

By April 1955, when Jonas Salk's approved polio vaccine was shipped nationwide, Penny had lost use of her legs, with both arms severely weakened. Their father later told the children that she had received the placebo.

But she retained determination, wit and patience enough to earn a college degree, marry, raise children and work 35 years for Fresno County and Fresno's Community Regional Medical Center, helping connect people with services.

She was "incredibly resilient," said Jim Miller, of Fresno.

In all, three of the seven Miller children would contract polio, posing steep challenges for their parents, a newspaperman and a nurse. Penny's case was the most severe, requiring long hospital stays, several surgeries and the implantation of steel rods to keep her spine straight.

At 6, "she spent three months in this iron lung, looking out at the world from a tilted mirror that was just above her face," Jim Miller said.

A few years later, after the family had moved to California's San Joaquin Valley, her younger brother Erick said, "she spent a year in a full body cast in our living room."

But she emerged strong enough to attend school alongside Erick, a year younger. From seventh grade to the end of 12th grade at Hoover High School in Fresno, he pushed her wheelchair from class to class. Both earned top marks.

"She definitely knew what she needed and she was not shy about speaking up," said Erick Miller.

Her sister Joanna Miller Hoffman of Simi Valley remembers Penny braving risky rides at the Fresno County Fair, sneaking out for a midnight swim at a community pool, and bucking her father's wishes in order to attend rock concerts with a boyfriend.

After high school, Foreman went on to Cal State Fresno, where she earned an English degree and teaching credential. Soon after, she married and gave birth to a son, Josh Coddington.

She also learned to drive a specially outfitted van; campaigned for the rights of people with disabilities; and began work for Fresno County, first in social services, later helping hospital patients get help and handle paperwork.

Her first marriage didn't last long. After it dissolved, her sister Joanna recalled, "she was a single working mother with a baby. And yet I'd go to see her at her house, and her house was cleaner than I was keeping my apartment."

When her son complained about one small thing or another, he remembers her telling him: "If you have something that’s a challenge, figure out a way through it. There’s always a solution.”

In 1986, Josh's mother married Robert Foreman, gave birth to a daughter and became stepmother to six children from her husband's previous marriage. And she continued working. The family home in Clovis was busy.

"It was a family of 10 in the house for a long time," her daughter, Holly Foreman, said.

Still, on many weekends and holidays Foreman steered her van toward Yosemite, Lake Tahoe, Disneyland or the Ventura County coast, a couple of kids aboard. Later, she'd often join one or two sisters for museum exhibits, theater or concerts in Los Angeles.

Family members said Foreman worked into the early 2000s, when weakening muscles and lung problems forced her to retire. Her husband died in 2016.

Foreman spent the last 3 1/2 years at Pacifica Hospital of the Valley in Sun Valley. She was dependent on a ventilator but remained in touch (and frequent “Words with Friends” competition) with loved ones, using her iPad as a window to the world. She was there when the COVID-19 pandemic erupted in March.

"We knew if COVID got anywhere near her, she had no defense," said Hoffman.

About a week before Christmas — a few days after the first COVID vaccinations in the U.S., but before any vaccine could reach her — Foreman tested positive. Once again, a notorious virus had reached her just ahead of a new vaccine. On Dec. 29, Foreman died, age 73, her death attributed to pneumonia and COVID.

Besides her lifelong tenacity, family members said, they would remember her excitement and laughter at a family Christmas party 10 days before her death.

Gathering by Zoom, two dozen relatives from three generations sang and rang chimes through three carols.

“She was someone who really took life and made the best of it,” said Josh Coddington.

Foreman is survived by daughter Holly Foreman of Fresno, son Josh Coddington of Phoenix, granddaughter Quinn Coddington; stepchildren Erik, Joel, Jacob, Michael and Paul Foreman and Amber Benoy; and siblings Jim Miller, Erick Miller, Alan Miller, Matt Miller, Laurie Mobley and Joanna Miller Hoffman.

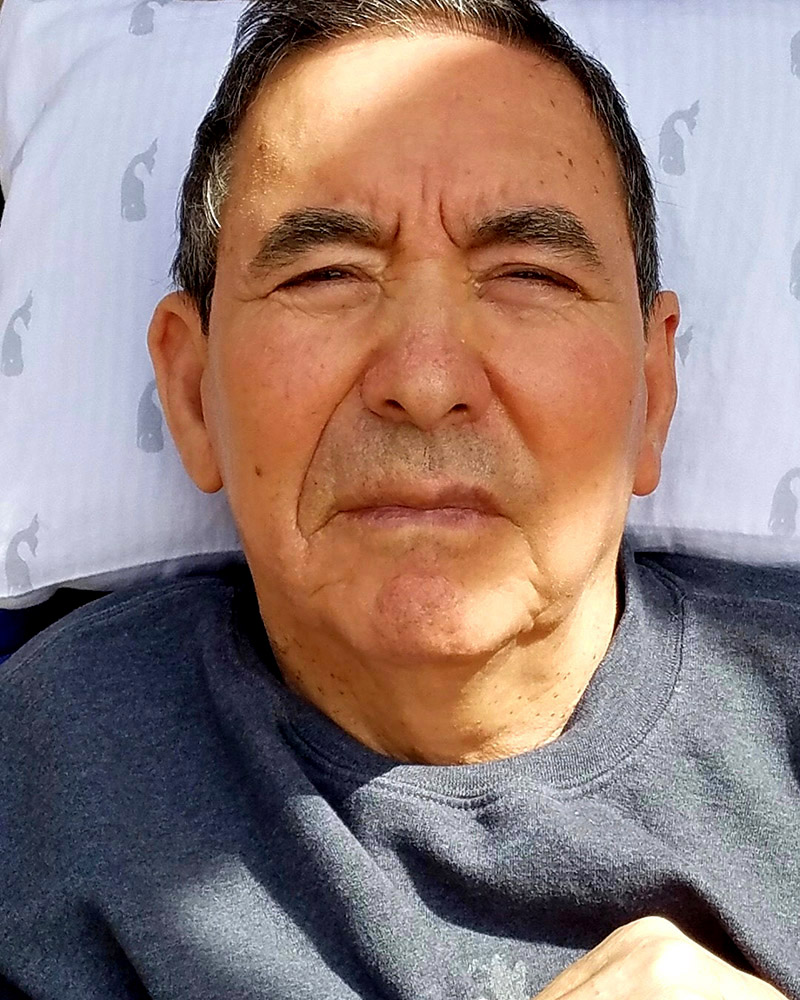

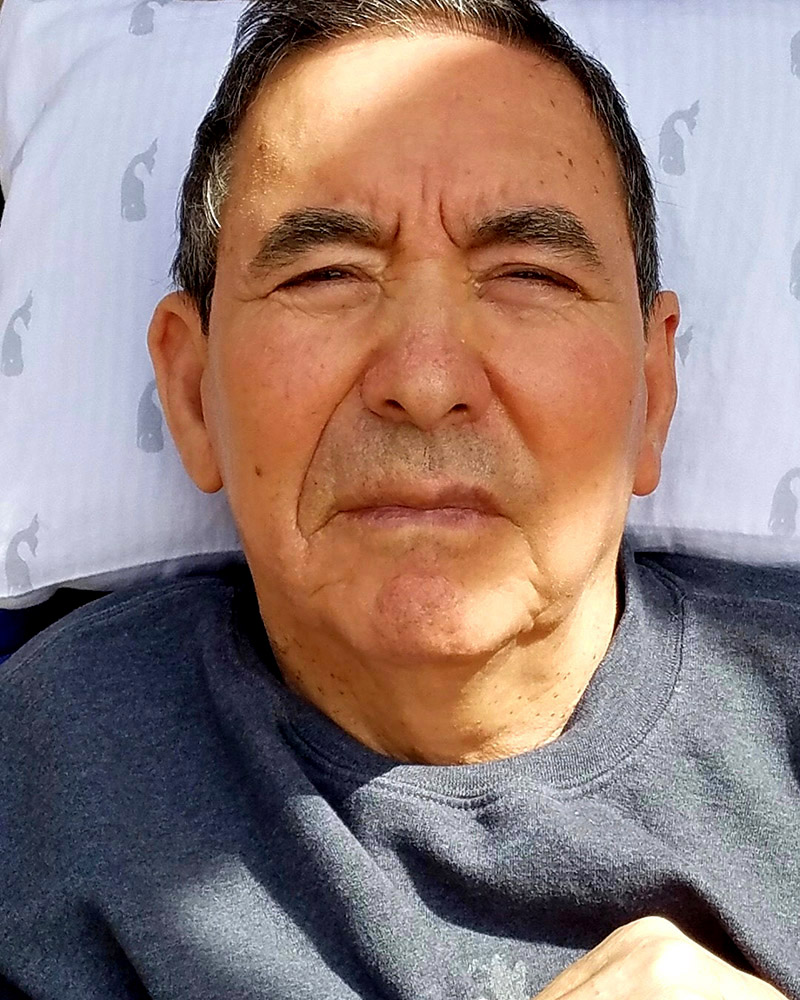

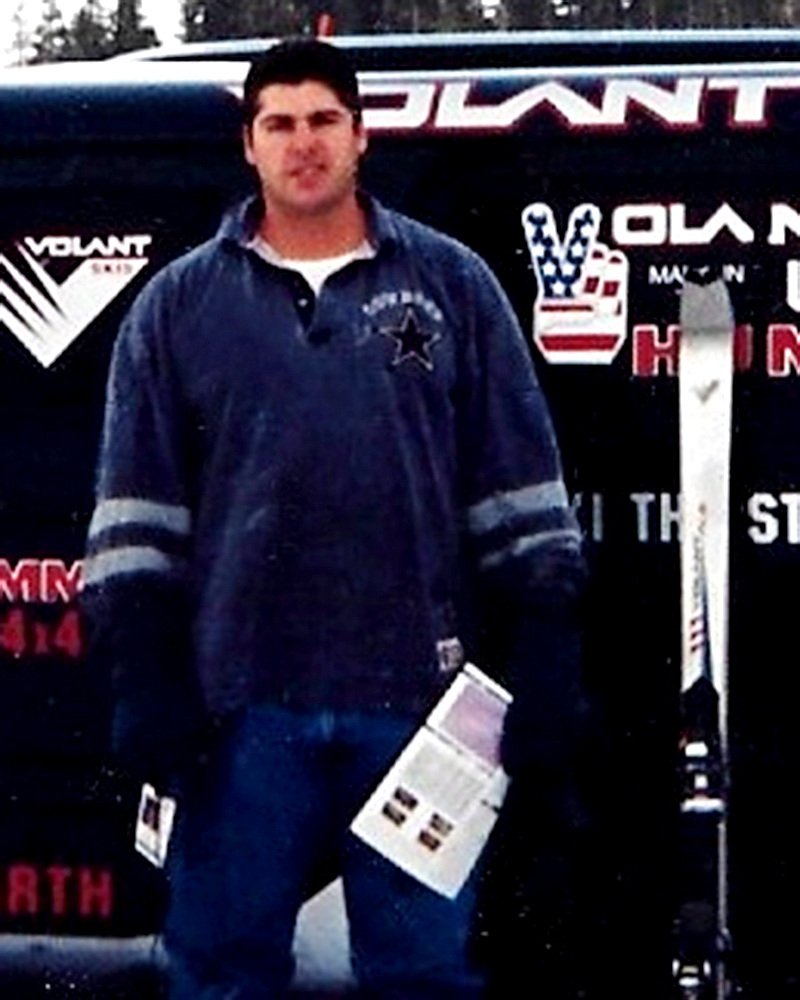

Alfonso Ye Jr.

25, Chula Vista

Alfonso Ye Jr., 25, stood out among classmates in the pharmacy tech program at Pima Medical Institute in Chula Vista.

Rather than waiting to complete the eight-month training program, he sat for his pharmacy license and passed the exam. And he began working at a local pharmacy while still completing his studies.

“He took initiative. That is quite impressive for a student to be able to pass that exam,” said his instructor, Benjamin Montoya.

Ye also took pride in his cooking skills, impressing the pharmacy department at potlucks with dishes he mastered as a professional cook for the San Diego Yacht Club. Ye studied psychology at San Diego Miramar College, and graduated from Mira Mesa High School, according to his LinkedIn profile.

A manager at the pharmacy where Ye worked, who asked not to be identified, described him as likable and outgoing.

Montoya last saw the bright student in early March. Ye returned to his mother’s home in Riverside County with what the family believed was a cold with a high fever. He died March 25 at home in La Quinta.

He is preceded in death by his father, Alfonso Ye Sr., who died in 2018, and is survived by his mother.

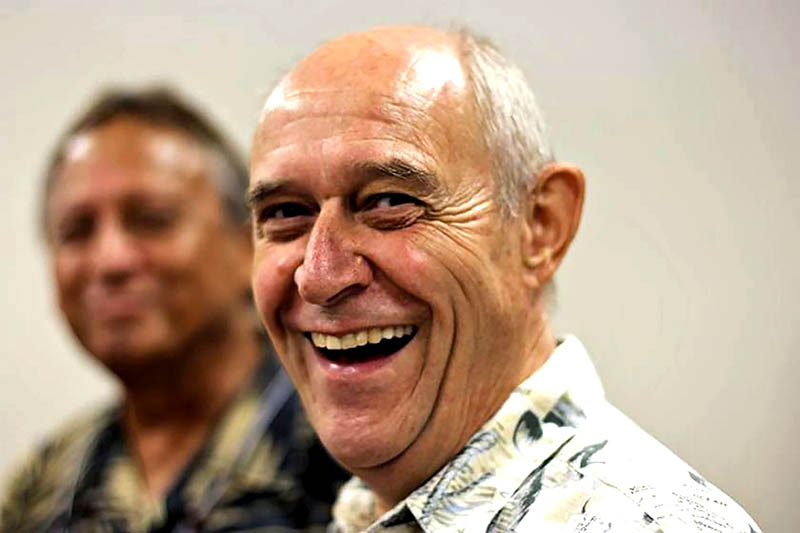

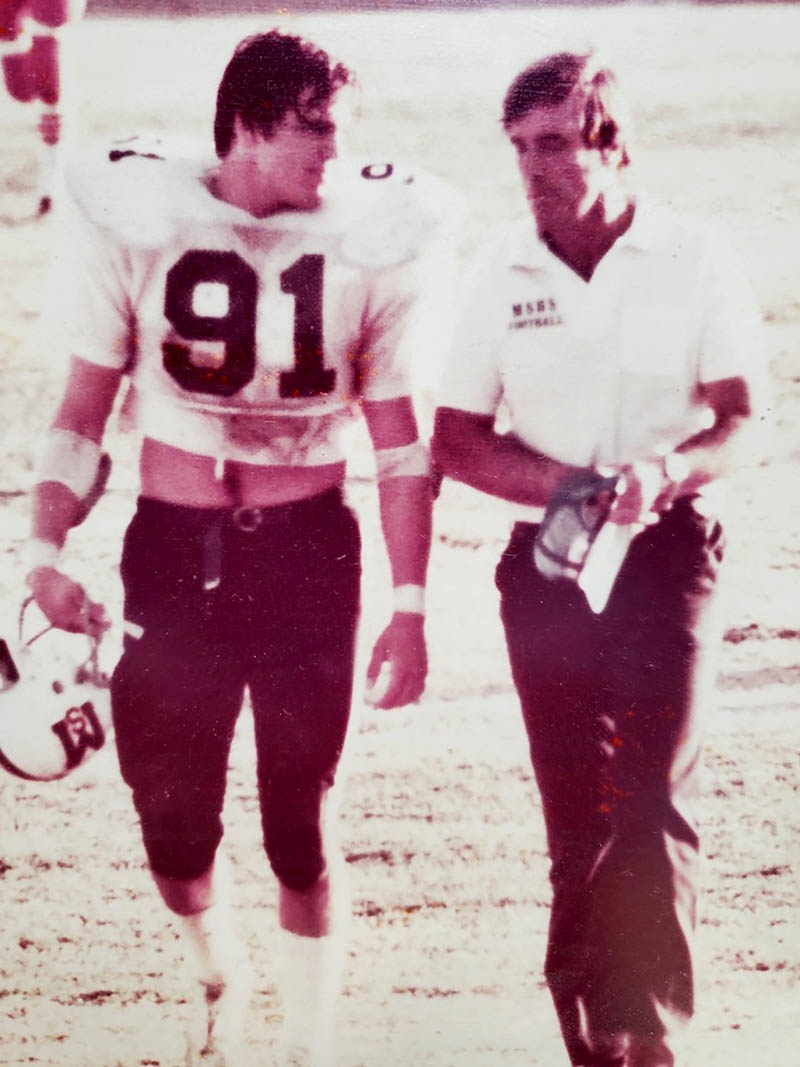

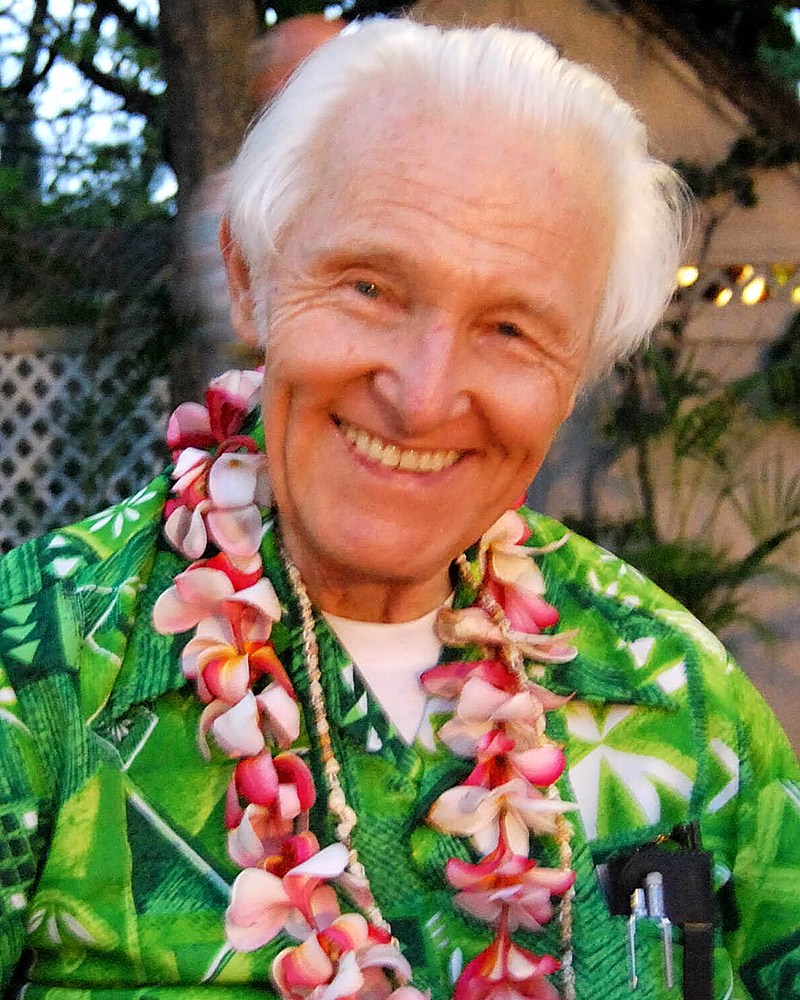

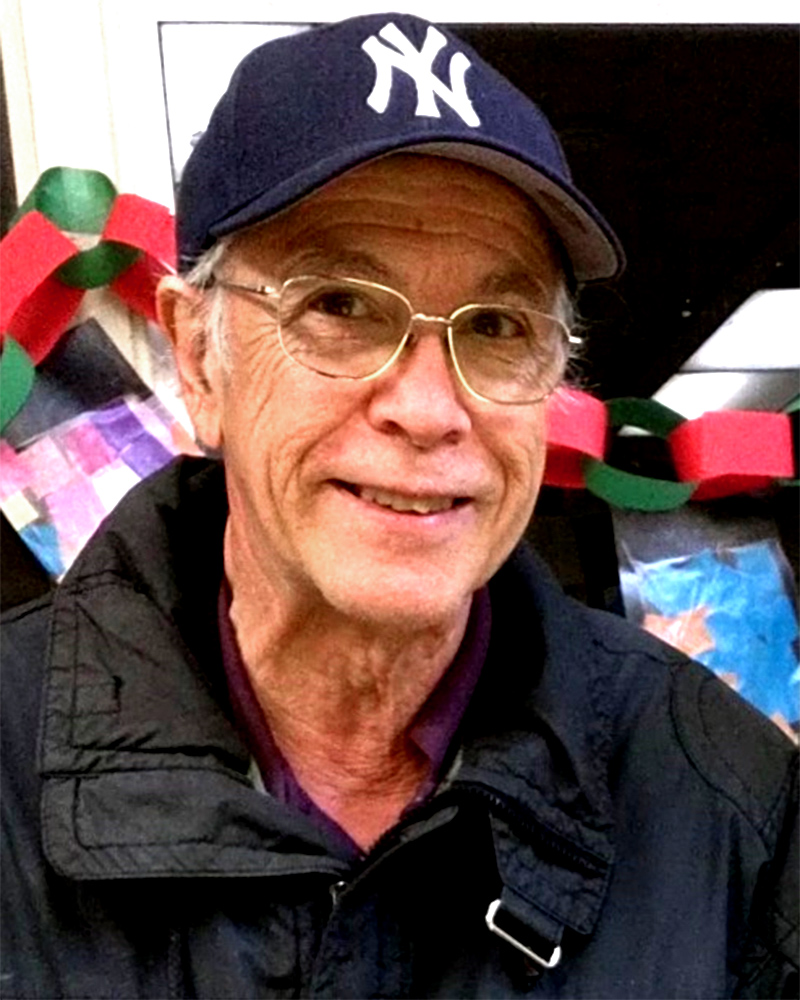

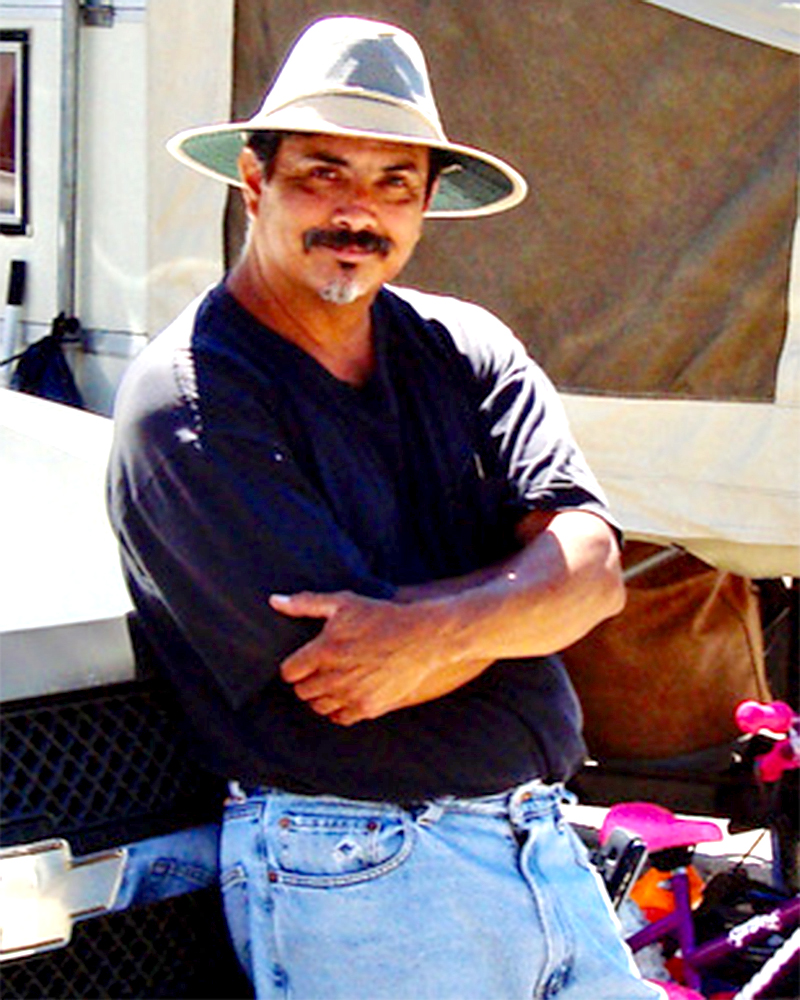

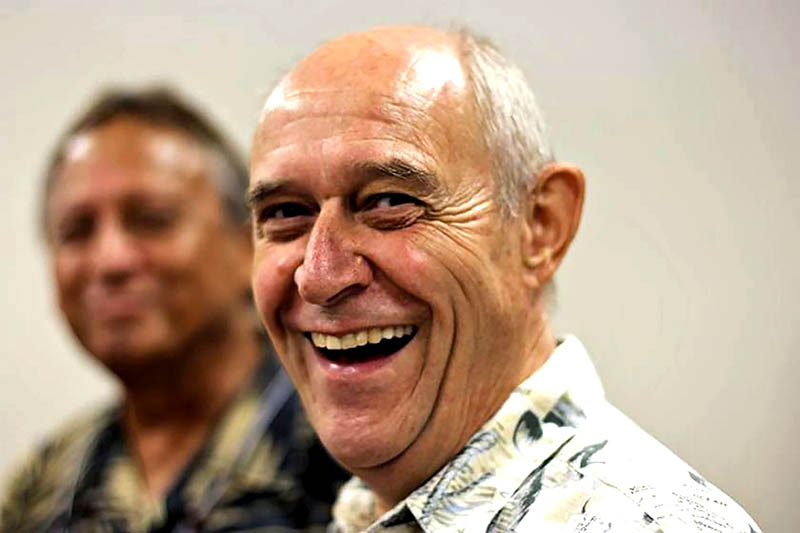

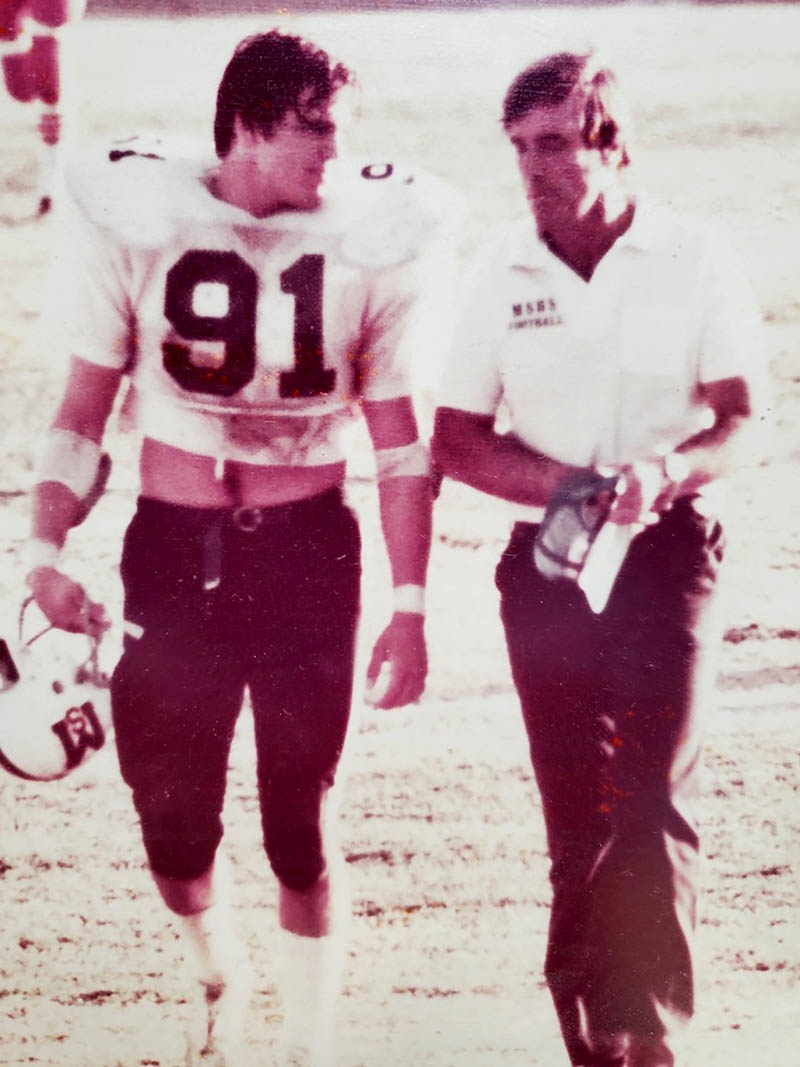

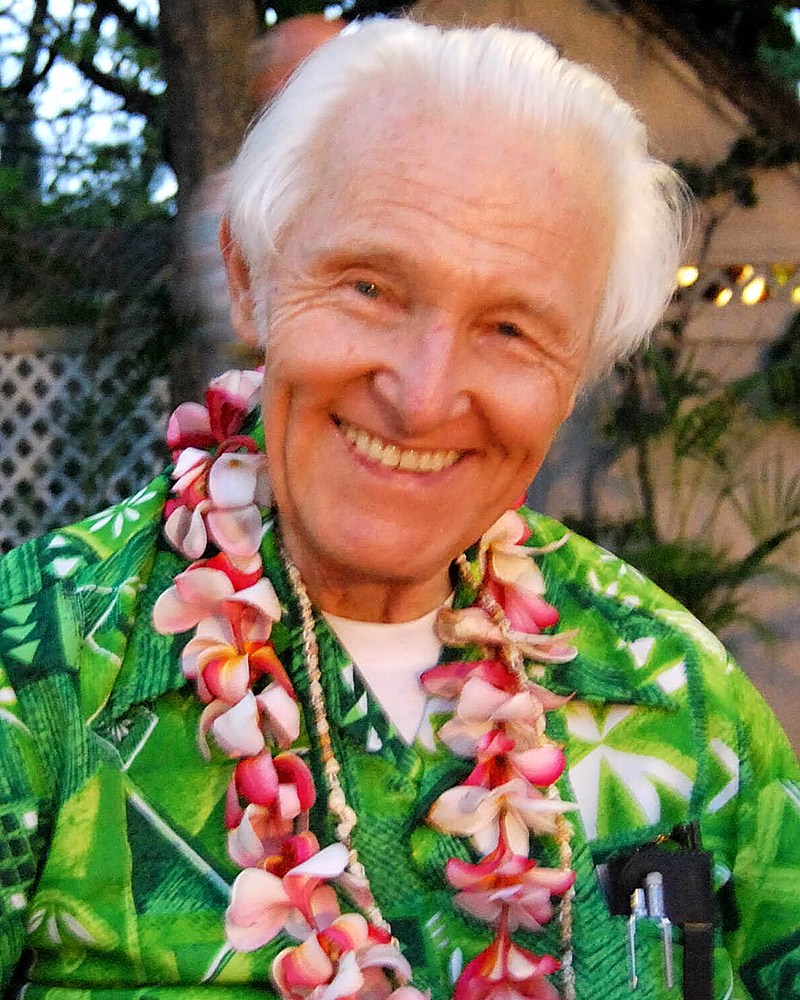

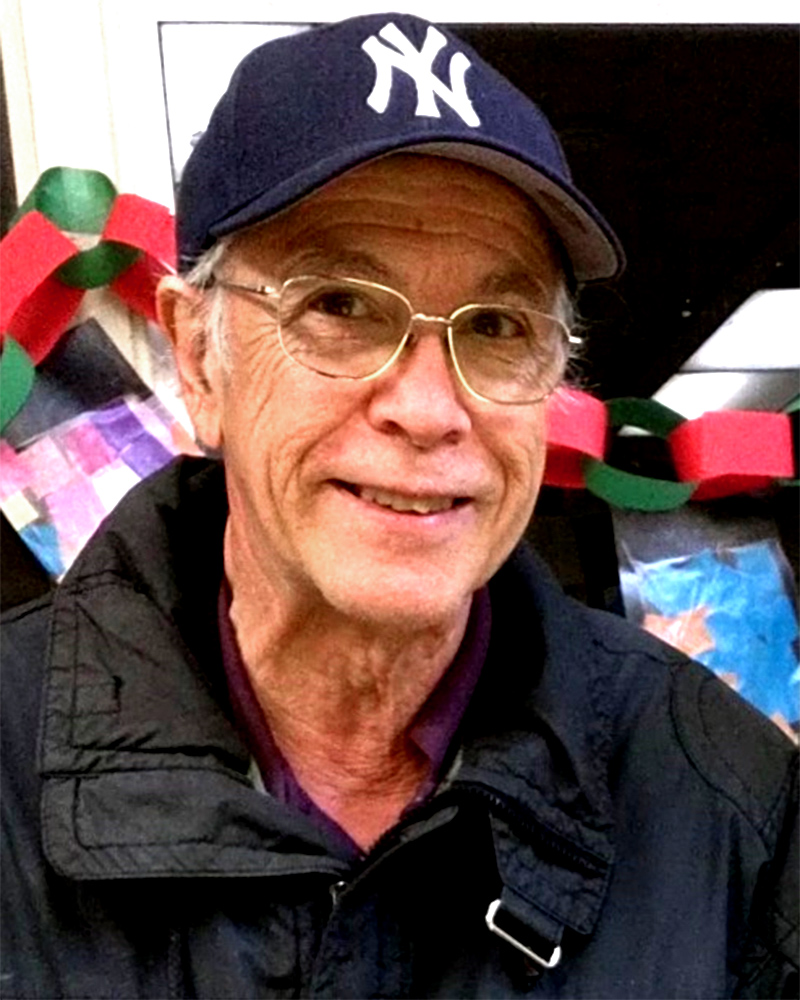

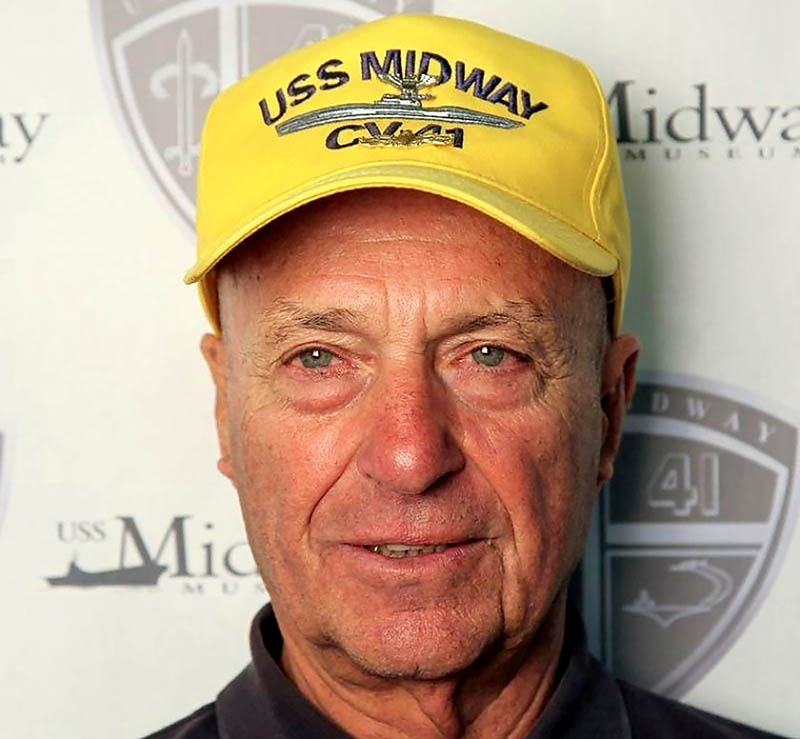

Vic Lepisto

75, Agoura Hills

Other than his family and the young people he coached, Vic Lepisto led a self-contained life, making it to 75 without an email address.

Grit and determination, honed in a life of physical action, carried him through as he fought diabetes, dementia and then COVID-19, dying peacefully Dec. 28 after a three-week battle.

Born June 29, 1945, Lepisto grew up in unincorporated La Cañada and played football and baseball and ran track at John Muir High School in Pasadena.

Entering UCLA in 1963, he played two sports. As a defensive end on the "Gutty Little Bruins" football teams led by Heisman winner Gary Beban, he competed for national championships. He co-captained the 1968 team.

His performance on the rugby pitch earned an induction into the UCLA Rugby Hall of Fame. He continued to play after graduation, and holds a spot in the Santa Monica Rugby Club's hall of fame.

At Mom's, a Westwood dancing spot, Lepisto met 21-year-old Sue Henderson in 1970. A brief courtship was interrupted by his desire to explore Europe before marriage. A month into the expedition, he called, and she answered. She joined him in Rome, where he proposed.

Upon learning that 10 witness signatures would be required at the American Embassy, they took a ferry to Athens and found an American church whose minister's prime concern seemed to be the odds of the union lasting.

Twice, he "pointedly said to me, 'Did you know that one out of three marriages here ends in divorce?'" she recalled.

Sue, who has spent 43 years as a teacher, counselor and principal with the Los Angeles Unified School District, got the last laugh. The marriage lasted 50 years.

The couple settled in North Hollywood. With a daughter and two sons, they eventually made Agoura Hills home.

"His children were the light of his life!" Sue Lepisto said. "He was omnipresent on the sidelines at youth basketball and soccer games, cheering from the dugout at baseball games and imploring runners to ‘GO’ down the homestretch at track meets."

After 14 years as a Los Angeles County probation officer, Lepisto retired to go into teaching. At El Camino Real High School in Woodland Hills, he taught physical education and coached cross country and track for another 14 years.

He retired in 2010 to have more time for family, exercise and travel.

He is remembered for "his kindness, selflessness, loyalty, determination, and love for his family," said his son Garrett. "Vic gave his all to others, always putting them ahead of himself and celebrating the success of those around him."

He is survived by Sue, their three children, eight grandchildren, his sister Carol, brother Dave, cousins, nieces, and nephews.

Frederick K.C. Price

89, South Los Angeles

The Rev. Frederick K.C. Price, a televangelist who founded the Crenshaw Christian Center, a South Los Angeles megachurch with a 10,000-seat sanctuary, died Friday from COVID-19. He was 89. His family said he had been in the hospital suffering from the virus infection for the last five weeks.

Opened in 1989 on the former site of Pepperdine University, Price’s South Vermont Avenue church was topped by a massive aluminum sphere known as the FaithDome, 320 feet in diameter and 63 feet high. At the time, newspapers proclaimed it the largest geodesic church structure in the world, and it remains a landmark visible to air travelers arriving at Los Angeles International Airport.

“He chose to build the FaithDome in the inner city, as opposed to doing it in the suburbs, because he wanted to minister to the disenfranchised,” said Angela Evans, his daughter and the church president. “He had a heart for his own people, people of color. He wanted to lift them out of their ills and raise their hopes, that in God they could be something, do something, raise their children well.”

The Crenshaw Christian Center has served as a coronavirus testing site since early in the pandemic, and recently as a vaccination site. In a statement, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti described Price as “a towering giant of our faith community in Los Angeles and an inspiring force for justice worldwide,” and added: “His ministry had local roots, but a global impact — providing care, resources, and a helping hand to the most vulnerable in our city and far beyond our borders.”

A Santa Monica native, Price met his future wife, Betty, in the early 1950s when they were both students at Dorsey High School. Price’s family says his religious awakening began when he followed her to a Christian tent revival service. He joined her at a Baptist church, and preached for years while making a living at other jobs, such as driving a truck for Coca-Cola.

“He was the consummate family man, and that’s one of the hallmarks of his ministry and his life,” Evans said. “That’s why his children are so devastated. He was everything.”

She said her father wrote more than 50 books on religious themes. Price and his wife were married for 67 years. They lost an 8-year-old son when a car struck him in 1962.

“He was generous to his children,” said Evans. “If they needed something, he didn’t say, ‘You know, I pulled myself up by my bootstraps, you do the same.’”

Price founded the Crenshaw Christian Center in Inglewood in 1973, and his popularity was hugely boosted by his appearance on television and radio, including a show called “Ever Increasing Faith.”

Price was a preacher in the charismatic tradition, with a belief in miraculous healing. He also preached what some described as the “prosperity gospel,” or the idea that God rewards faith with abundance, material and otherwise.

As crowds multiplied, Price dreamed of assembling his congregation in one room. Frederick Price Jr., who took over his father’s pulpit in 2009, said his father got the idea for the FaithDome after walking into the geodesic dome that used to house the Spruce Goose seaplane in Long Beach.

“He realized we needed another building. ‘How can we get everyone in the same building? How can we get a good seat for everyone in the house?’” he said. “The geodesic dome can be pillarless. He said, ‘Yeah, this is it.’”

The geodesic dome was also much cheaper than traditional architecture would have been for a sanctuary of its size. When the FaithDome opened in 1989, The Times called it “the nation’s largest house of worship,” with a 16,000-member congregation that made it the largest Protestant church in Southern California.

“We’re located where we are, where others might not want to come in and help,” said Price Jr. “It was important to him to be that oasis in the desert, so to speak.”

The church has a school and a youth center, hosts food and blood drives, and does prison outreach. It employs about 150 people. At times, the church has boasted membership of 28,000, a number the family says encompasses parishioners throughout its history.

Price Jr. said that before the pandemic, the church had a congregation of roughly 6,000 people, a number that he estimates has grown massively during COVID-19 lockdown, with online videos reaching 20,000 to 30,000 viewers.

Besides his widow, Price Jr. and Evans, Price is survived by daughters Stephanie Buchanan and Cheryl Price, as well as 10 grandchildren.

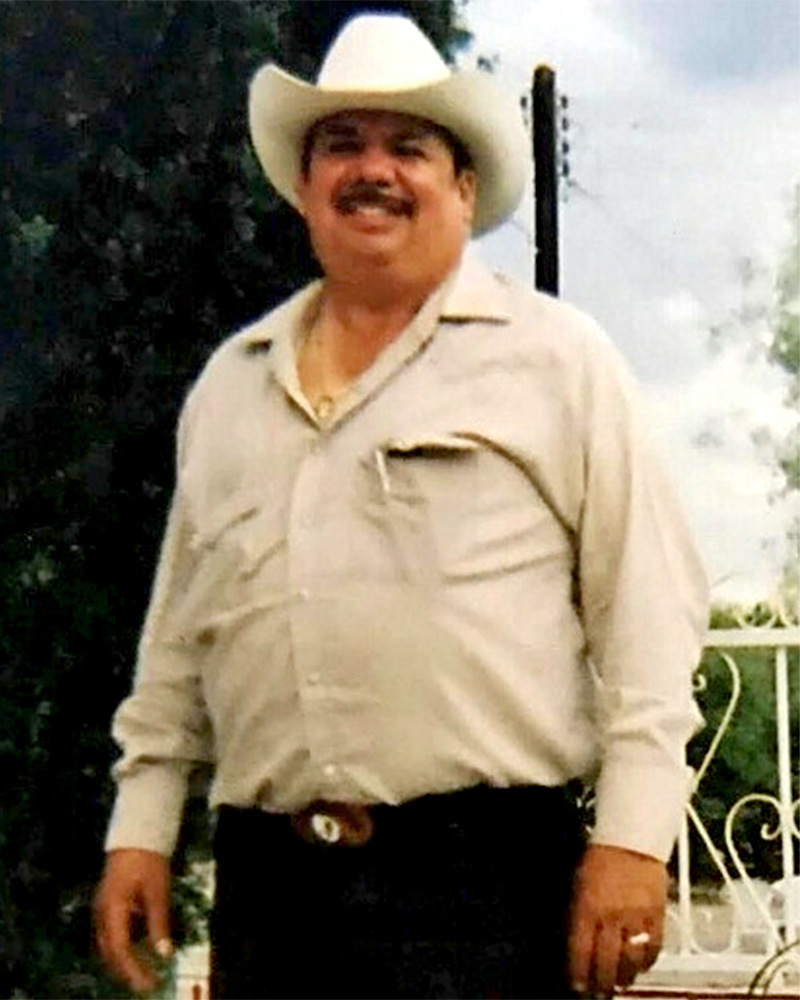

Taurino and Silvia Rivera

57 and 56, San Diego

When Taurino and Silvia Rivera were laid to rest beneath a California pepper tree on a Friday morning, their white caskets were surrounded by their three sons and daughters-in-law and

seven grandchildren, members of the church they founded in San Diego and pastors who had grown close to them during their years of ministry.

The couple, who had grown up together in a small town in Oaxaca and had been inseparable since, were buried together after dying weeks apart from COVID-19. Taurino’s casket was lowered first, and then his wife’s on top of his.

Missing from the scene was their fourth son, Ismael Rivera, who watched the final moments of the ceremony on his phone while standing outside a restaurant in Tijuana. Jesimiel Rivera, the third son, held his phone over the grave as his brother sobbed on the other end of the Zoom call.

“In that moment, thousands of thoughts just raced through my head, with one question lingering — why?” said Ismael Rivera, who prefers the name Isaac.

The second of the four siblings, Isaac, had not been able to see his parents for almost a decade. He had been counting down to the summer of 2021 when he would no longer be banned from the United States and could request a visa to visit his family. His parents were not legally in the U.S. and could not cross south to see him.

At the funeral, the oldest son, Joel, read a letter from Silvia’s father in Oaxaca, who hadn’t seen his daughter since she left roughly 30 years ago. His hands shook as he held the piece of notebook paper.

“I love you forever,” he read in Spanish. “I will carry you in my heart.”

The Rivera family immigrated to the United States in the early 1990s when the four brothers were young children. They made City Heights in San Diego their new home.

Silvia and Taurino began working at a McDonald’s together, rising as early as 3:30 a.m. to arrive on time for their morning shifts.

The family didn’t have much money, but the sons said their parents always found a way to celebrate birthdays and take care of them. And even before the parents shifted to working full time as pastors, faith was a big part of family life.

Jesimiel, remembered sitting on the floor as a child and watching his father play worship songs on a guitar.

“Just seeing dad so big and the song and his voice, and then everybody around, the adults were just clapping and singing — everything was so joyful,” Jesimiel said. “I remember feeling in a magical place at that moment.”

He remembered, too, going as a teen with his father to minister at a rehabilitation center, and the way his father’s words would ease the people there.

Taurino took Daniel Rivera, the youngest of the four sons, to piano classes as a child, and they would play together. Daniel eventually became a pastor as well.

The family home would fill with people who needed help — a couch to sleep on, some food from the refrigerator.

“They left a big legacy for me and my brothers to follow,” Isaac said.

In recalling their mother, each son remembered intimate moments when they were alone with her, and the safety and love they felt in her presence.

Even after Jesimiel became an adult, she could always sense when something was bothering him.

“I could hide things from Dad, but never from Mom,” he said.

And, of course, they remembered her food — her chilaquiles, her atole, her spicy chicken soup and her mole.

The brothers cannot cross the border to console with Isaac without also becoming stuck outside of the U.S., though the three are protected for now by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, which grants work permits and temporary protection from deportation to undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children.

In 2011, the year before the program was created, Isaac was stopped at one of the Border Patrol checkpoints that are scattered across the southwestern United States and ended up voluntarily returning to Mexico. Because of U.S. immigration laws, he was barred from coming back for at least 10 years.

“What hurts me a lot is that for the last 10 years, I wasn’t over there to tell them how much I love them, how much they meant to me, hugging them really tight and telling them, ‘I love you, Dad. I love you, Mom,’ and being there on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day and their wedding anniversary and birthdays,” Isaac said. “And now that will never happen.”

One of the things that brings him comfort now is that even in death, his parents are still together.

“They were two human beings glued together everywhere they went,” Isaac said. “Now they’re in heaven together forever and that’s what makes me happy. That’s the only thing that makes me happy.”

In 2011, Taurino and Silvia started a church called Fe Esperanza y Amor — faith, hope and love — and, according to the church members they left behind, they embodied those values in their work.

After the holidays, Daniel was the first in the Rivera family to show COVID-19 symptoms. He was hospitalized, followed by his mother Silvia and then his father Taurino.

Though Daniel recovered, Silvia and Taurino remained on ventilators. Early in the morning, on Feb. 1, Taurino died, and the family began to grieve and to plan for his burial.

Silvia seemed to improve. Doctors took her off the ventilator and moved her to a rehabilitation center.

No one told Silvia about Taurino’s death, but many believe that she figured it out on her own and followed after him.

“I think in a way she did know because my parents’ bond was so strong,” Daniel said.

Early on Feb. 19, Isaac got a call from his brothers across the border.

His mother, too, was now dead from the virus. He sat in his car and wept.

“I was barely dealing with the situation with my dad,” Isaac said. “Deep inside I’m hurting, deep inside I’m broken in so many pieces. I don’t know how I’m going to get myself back together.”

Daniel is now pastor at Fe Esperanza y Amor in addition to his own church in San Marcos. On his first Sunday preaching there after his father’s death, he told the church they would follow the guidance that his father had given them — to serve God and to live in peace.

He urged them to find solace in one of Taurino’s most common refrains. “God is good, all the time.”

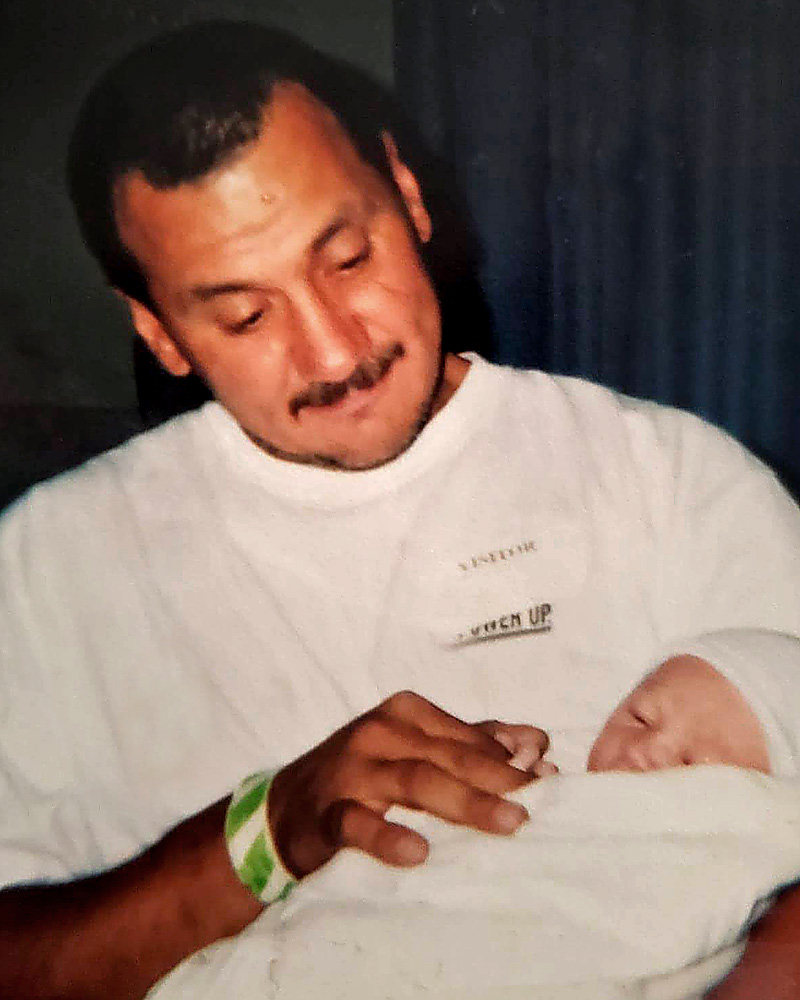

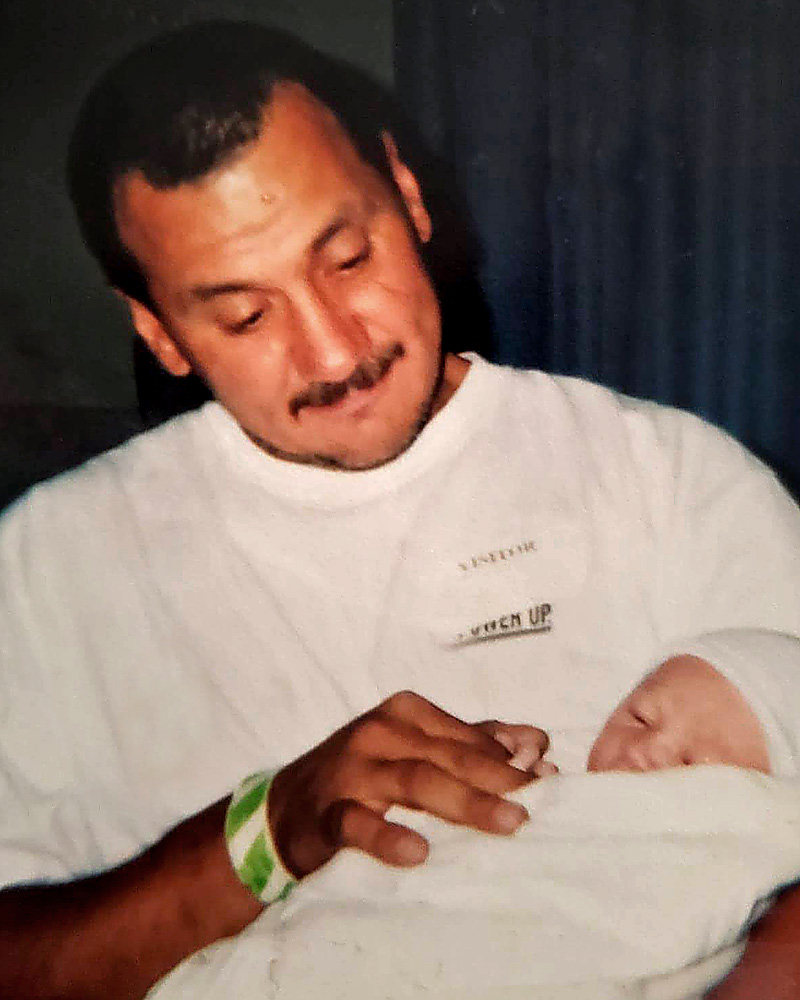

Vidal Garay

60, Los Angeles

At 5 feet 11 and just 150 pounds, Vidal Garay looked like he was all muscle when he was young.

“To me, he was like a superhero,” said Richard Garay, Vidal’s second son. He remembered his father telling him and his brothers never to be scared of chasing their dreams.

“You guys are American citizens,” Richard recalls him saying. “You guys can get your education and ... do whatever you want to do.”

Born in the town of El Nayar in Mexico’s Nayarit state, Vidal grew up poor on a ranch. He began working at age 5 or 6, collecting water from the river, grabbing satchels of corn and grinding it to make tortillas for dinner.

Vidal immigrated to the United States when he was 14. He worked the fields, climbed power poles to fix cables, and finally arrived at QueensCare Health Centers in East Los Angeles as a security officer.

Richard remembered his father leaving in the morning before the sun was up. But he said Vidal rarely spoke about how hard he worked.

After the family had dinner together, Vidal would take a shower and grab his favorite Spanish language newspaper, La Opinión. On his days off, Vidal would kick his feet up, sitting on the porch with coffee and cigarette, and spend hours poring over the newspaper.

For English reading, he loved nonfiction, such as David Bellavia’s “House to House,” about the Iraq war, and Marcus Luttrell’s “Lone Survivor,” about Navy SEALs in Afghanistan.

Vidal was known as a “cool dad,” Richard said. He was lively, savoring Spanish corridos, and largely left the teenagers alone. But he would sometimes come in and offer, “Do you guys want to hear a joke?”

“My dad was strict, don’t get me wrong,” said Richard. “But he never judged us. He never got mad when we did something bad. He just guided us.”

“We were always able to communicate anything and everything to my dad,” Richard said. Vidal always told him and his brothers that he wanted to be their best friend first and their dad second.

In his free time, fishing was Vidal’s favorite hobby. The family spent a lot of time fishing at the Redondo Beach Pier. Vidal was also a good cook. Besides fish, he was known for his pork riblets in red salsa.

A romantic, Vidal was vocal about emotions, writing letters to Norma, his wife of 34 years, and was never ashamed of hugging or kissing her in front of their children.

On May 29, Richard felt mild symptoms of COVID-19, with a headache and a runny nose. He self-quarantined for four days at home and got a positive test result on June 4. On the same day, Vidal also tested positive, after losing his sense of smell and taste.

The two spent days quarantining in the same room and briefly spoke about dying together. “If you go, then I’ll go,” Richard said his father told him.

Richard had mild asthma but hadn’t used an inhaler for more than 12 years. Vidal suffered from sideroblastic anemia, a very rare form characterized by fatigue, shortness of breath and feelings of weakness.

On the eighth day, Richard woke up gasping for air. It felt, he said, as if “somebody pulled a bag over your head.”

Richard was taken to the hospital. “The last words I told my father was, ‘Dad, I don’t think I’m going to make it.’ And that was the last time my dad saw me.”

Richard recovered. Vidal died June 20 at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center. He was 60.

Richard said 28 extended family members, including him and his father, have tested positive for COVID-19, most recovering at home, but they don’t know how they contracted the virus.

Vidal is survived by his wife, Norma; sons Juan, Richard and Benjamin; multiple siblings (his son isn’t sure how many), and three grandchildren. Another granddaughter is expected to be born soon.

Brittany Bruner-Ringo

32, Torrance

After she tested positive for coronavirus in March, nurse Brittany Bruner-Ringo quarantined herself in a Torrance hotel room, but she never stopped taking care of people.

The first employee infected in an outbreak at a dementia care facility in West Los Angeles, Bruner-Ringo called and texted colleagues that subsequently fell ill, encouraging them daily to keep a good attitude and reassuring them that they were all going to be OK.

“Brittany was our cheerleader,” one recalled.

The hopeful messages stopped in early April when a clerk at the hotel’s front desk summoned an ambulance for Bruner-Ringo. She was taken to Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, where she died in the intensive-care unit 19 days later. She was 32.

Growing up in Oklahoma, Bruner-Ringo saw a nursing career as a kind of birthright. Her mother and grandmother were nurses, and her personality was a natural fit for the field: Upbeat, empathetic and helpful.

“Helping others made our sister happy. She was so compassionate,” her sisters Breanna and Marriana Hurd wrote in an email to The Times.

After getting her degree as a licensed vocational nurse, she worked in Ohio and then a position as a traveling nurse brought her to L.A. She signed on full-time in 2019 with the Silverado Beverly Place, which specializes in treating Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia, and worked often with third floor patients with the mildest cases.

She loved sunflowers and coworkers described her as sharing the flower’s warm toughness. At staff meetings, she was known to speak up about residents she felt needed more attention.

“She was just kind-hearted. I don’t think she really thought of it as a job,” Breanna recalled in an interview. “She never complained about her job, even once, as much as we talked.”

Bruner-Ringo was in her near constant contact with family members back in Oklahoma. She and her sisters kept video chats open as they went through their days.

“When we weren’t on the phone, we would spend time texting and sending funny memes/videos in our group chat. Brittany was the funniest person we’ve ever known,” her sisters recalled.

When Silverado allowed a new patient from New York to move into the residence March 19, she called her mother, a veteran nurse in Oklahoma City, for advice.

Kim Bruner-Ringo told The Times her daughter said the man arrived with symptoms of COVID-19, including fever and coughing. The Silverado has denied this and provided medical records indicating he was asymptomatic when Bruner-Ringo initially examined him.

In any case, he was so sick the next day that an ambulance rushed him to Cedars-Sinai where he was diagnosed with COVID-19. In the weeks and months that followed, 89 other residents and staff contracted the disease. Thirteen would die.

Young and healthy, Bruner-Ringo seemed sure to beat the virus. Even after she was placed on a ventilator, she remained in good spirits.

The hospital nurses told her family “she would smile and her eyes were open most of the time. She was able to nod, follow commands,” her mother said.

Her vital signs were so strong that doctors discussed taking her off the ventilator, but the virus ultimately proved too strong.

She was buried May 1 in Oklahoma City. Her grave was covered with baskets of roses, zinnias, carnations, lilies. Her coworkers sent sunflowers.

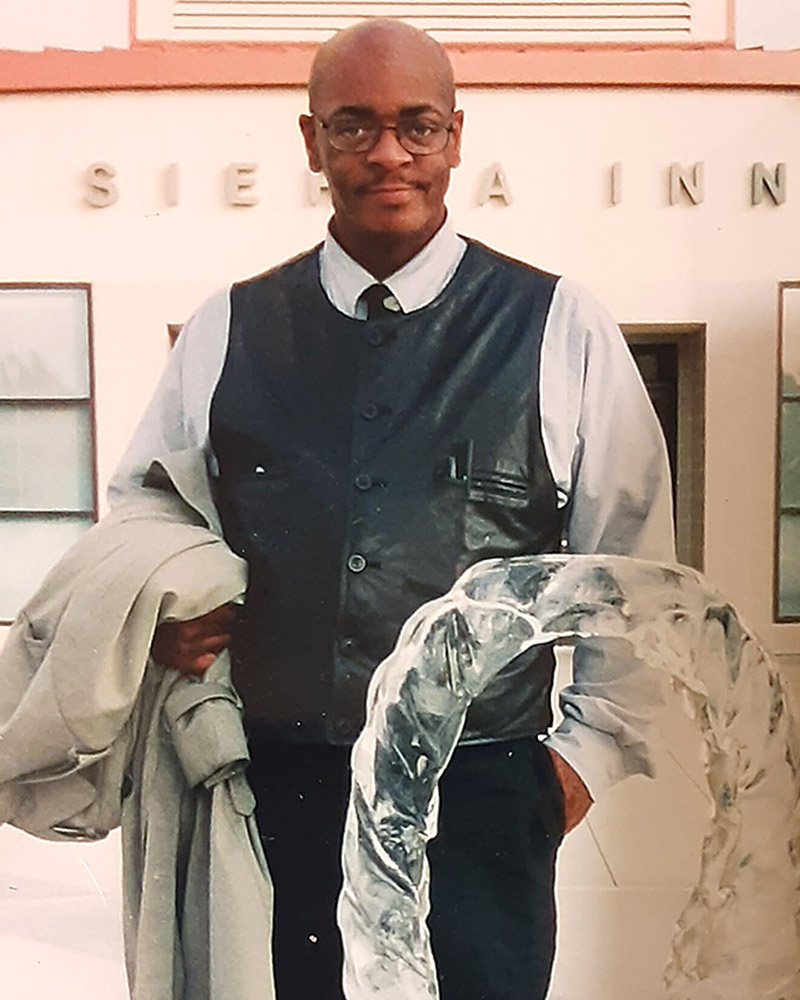

Read the full obituaryWilliam Minnis

70, Hayward

William Minnis loved people.

Known as Willy, he phoned family members and friends each week, sometimes more frequently, to pass along news and stay connected. He often broke into song during the conversations, even if he didn’t know all the words.

“He was the most caring person I ever met,” his sister Milo Minnis said.

Born in San Francisco and raised in Sacramento, William Minnis, 70, struggled with mental illness since his late teens. But his concern for others didn’t wane.

In his 50s and 60s, he roamed San Francisco’s streets each day. He befriended small-business owners and greeted people who patronized their shops. That fit with his friendly, outgoing nature and fondness for talking.

“They always called him ‘The Ambassador,’” Milo Minnis said. “As they got to know him, they just adored him. For someone who was mentally ill, that was unusual.”

William Minnis spent the last several years at the Morton Bakar Center, a skilled nursing facility in Hayward. He stayed up late, surfing the Internet on his iPad learning more about astronauts and space travel and the cosmos. He adored music, too, especially classic rock from the 1960s.

He fought COVID-19 for two weeks before succumbing to complications of the illness on Aug. 14.

Because of restrictions on visitors, hospital staff arranged an iPad on a table next to his bed so he could FaceTime family members as long and as often as he wanted. He had been in poor health before the illness and told his sister he didn’t want to be put on a ventilator.

“I think he really wanted to go,” Milo Minnis said. “His health had deteriorated so much that he said, ‘This is no way to live.’”

William Minnis is survived by his wife of more than 40 years, Carla Marion Minnis; his daughter Margaret Mae Moodian, a grandson and his sister. He was preceded in death by his parents and a brother.

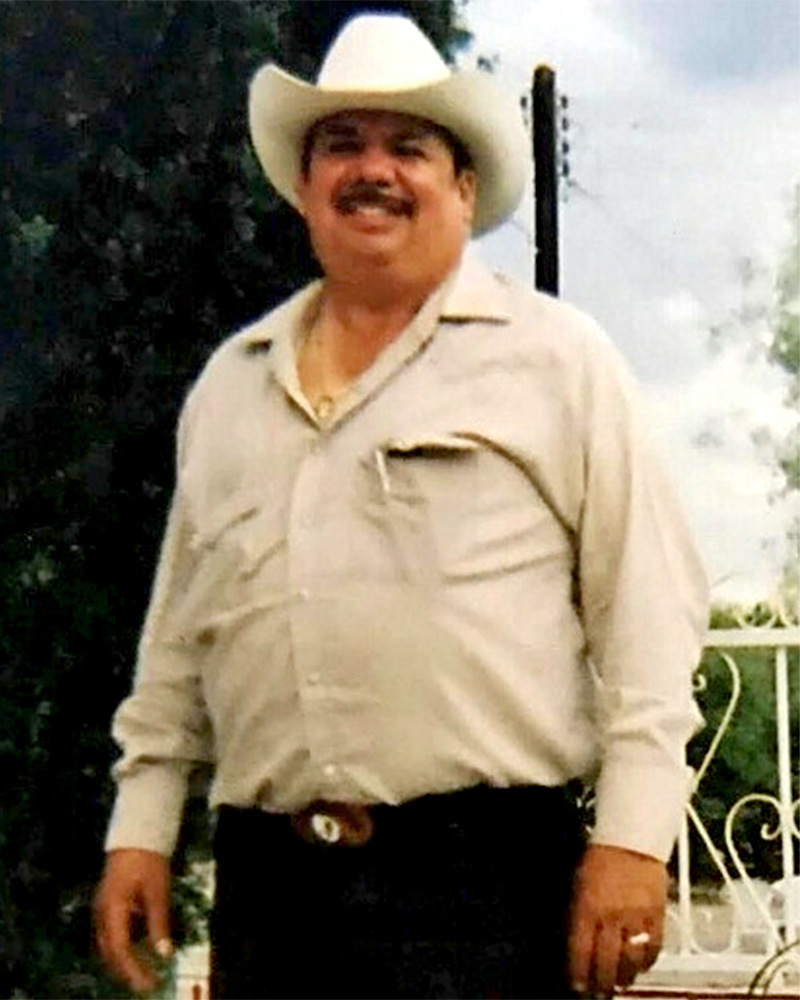

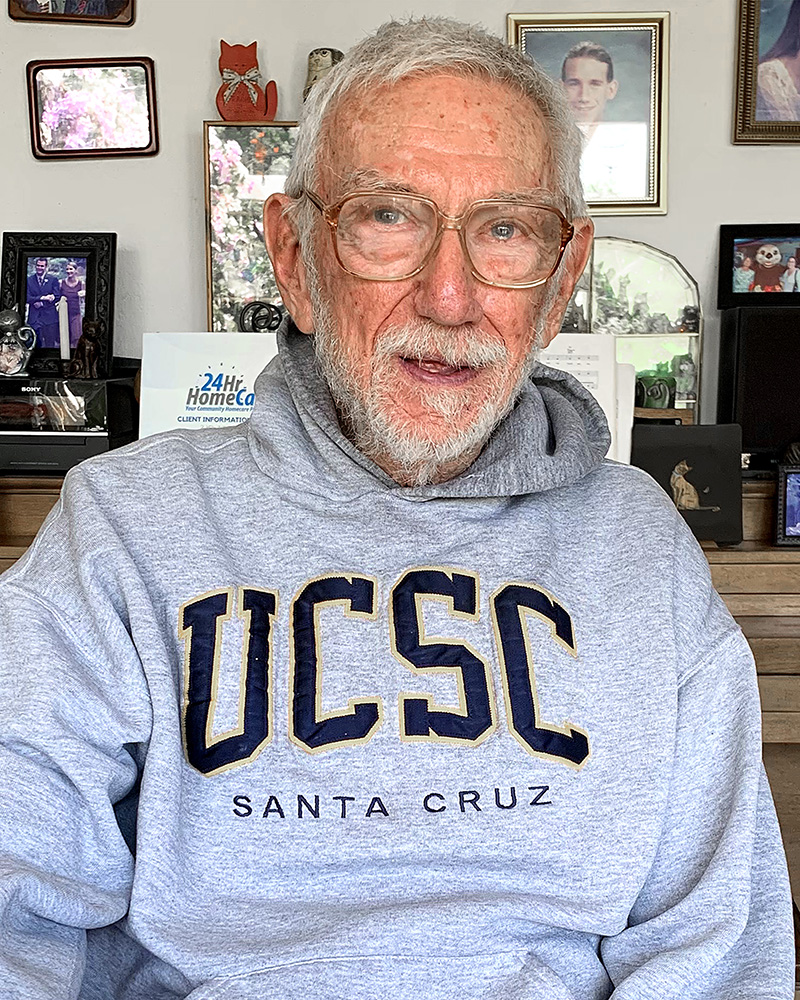

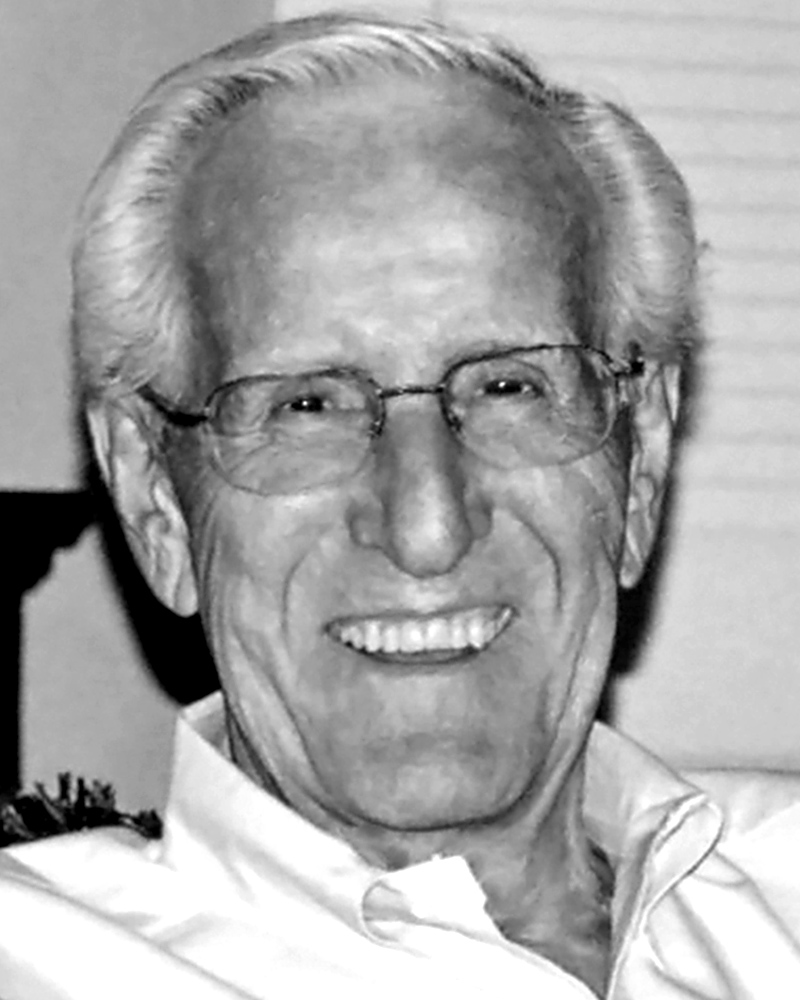

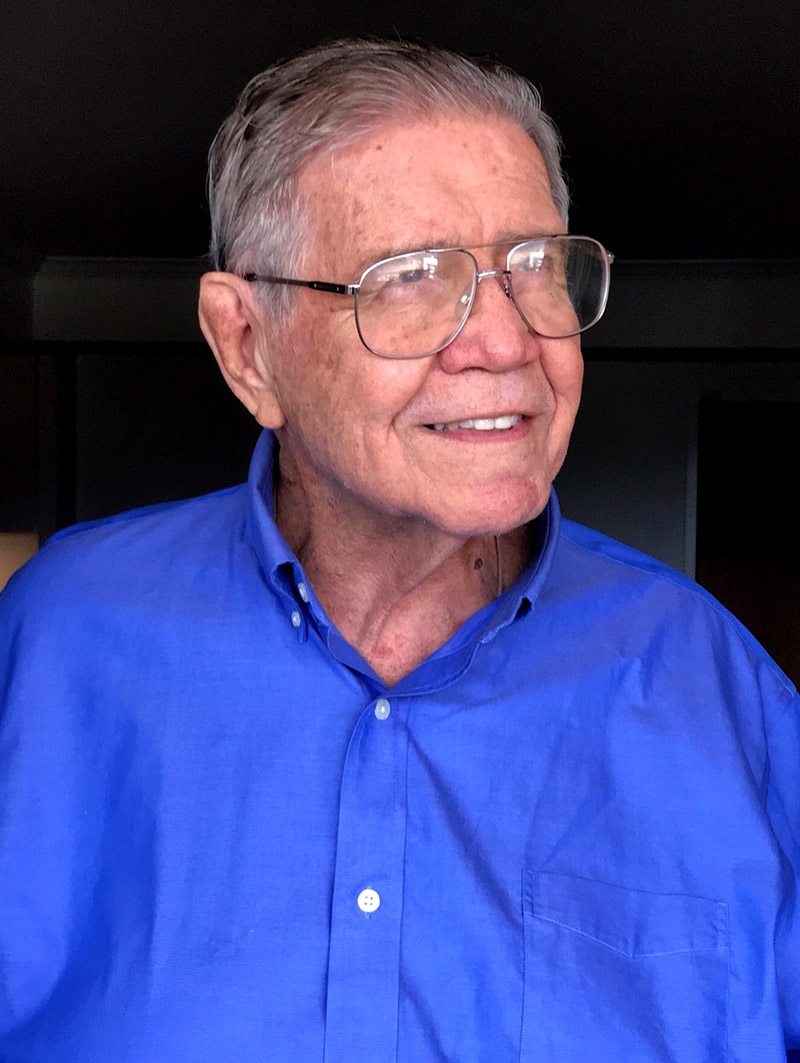

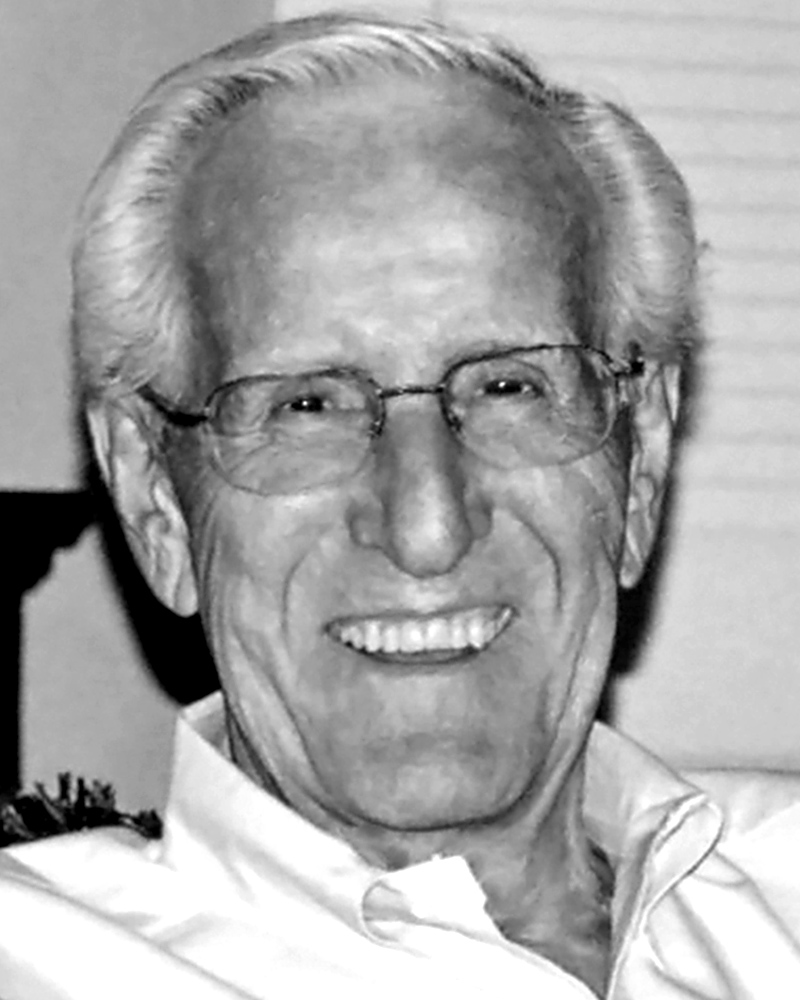

Richard Rutledge

87, Folsom

On Wednesday evenings in retirement, Richard (Dick) Rutledge would put on a bright purple dress shirt, a floral-print tie, white jeans and cowboy boots. With his wife, Norma, who wore a flared skirt that matched his tie, he was off to their weekly square dancing class, “Skirts and Flirts.”

In more ways than one, Rutledge and his wife were the perfect match. While their children remember their mother as the energetic, strict one in the house, Rutledge was the calm, steady presence who kept the family in balance.

“He kept us centered; he never got flustered,” his eldest son, Bill, remembered. “Everything was under control when he was around.”

When Norma died five years ago, Rutledge moved from their San Leandro home, eventually landing at Oakmont Senior Living in Folsom, where he contracted COVID-19. In mid-April, after the first case erupted at the home, almost all residents were tested. Rutledge, along with 17 other residents and three staff members, tested positive.

Two weeks went by without any symptoms, but suddenly his fever spiked and his breathing became troubled.

“It happened very quickly,” Bill said. “He just crashed.”

Rutledge died on May 6 at the nursing home with a hospice nurse by his side. His family, unable to enter due to COVID-19 restrictions, said their farewells the night before, through the window by his bed.

The 87-year-old was a rare third-generation San Franciscan, born into a small home in the Noe Valley district, and remained a Bay Area resident for most of his life. He attended Notre Dame University and went on to serve five years as a lieutenant in the U.S Air Force Reserve, after which he went back to school at UC Berkeley to earn an MBA. But soon after, with the early realization that computers would be the wave of the future, he enrolled at Holy Names College in Oakland to study mathematics and computer science, and then began his long career as a computer systems analyst for various companies.

His career, while successful, was more about pragmatism than passion. More than anything, he saw it as a reliable way to support his family, according to Bill. His children describe him as the ultimate family man, and a real people person.

“It sounds cheap to say, but it’s true: Everyone liked him,” Bill recalled.

Bill remembered a story that captures his father’s charm: Rutledge and his wife first met on a blind date in 1960. When he asked her, "Do you like chicken?" Norma said she did. Offering his arm, Rutledge said, "Grab a wing." A month later, they were engaged.

Survivors include his six children, Bill, Mary, Joyce, Robert, Stephen and Susan, and eight grandchildren. Due to restrictions on public gatherings, no funeral service is currently scheduled.

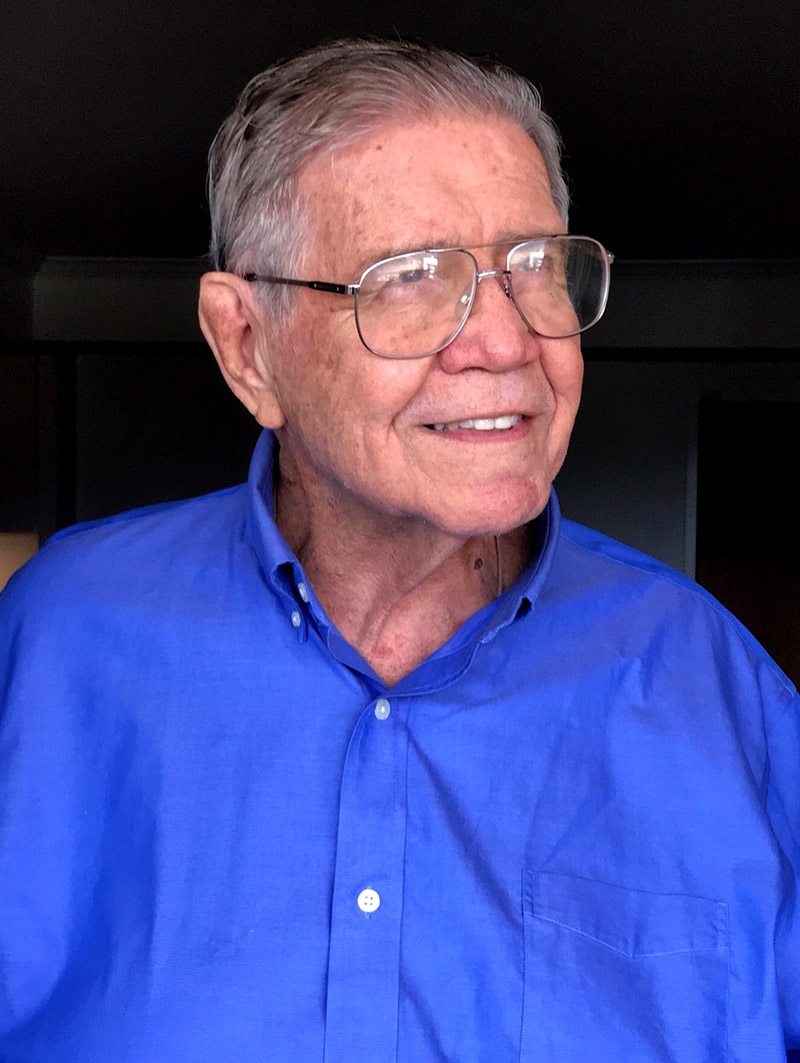

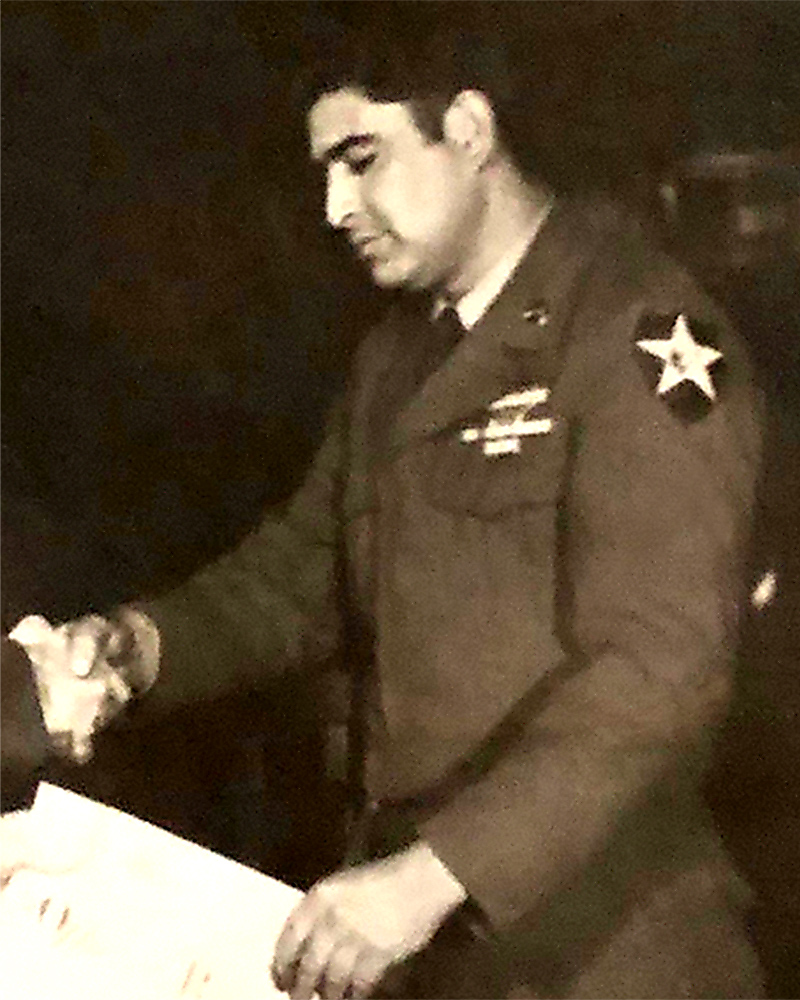

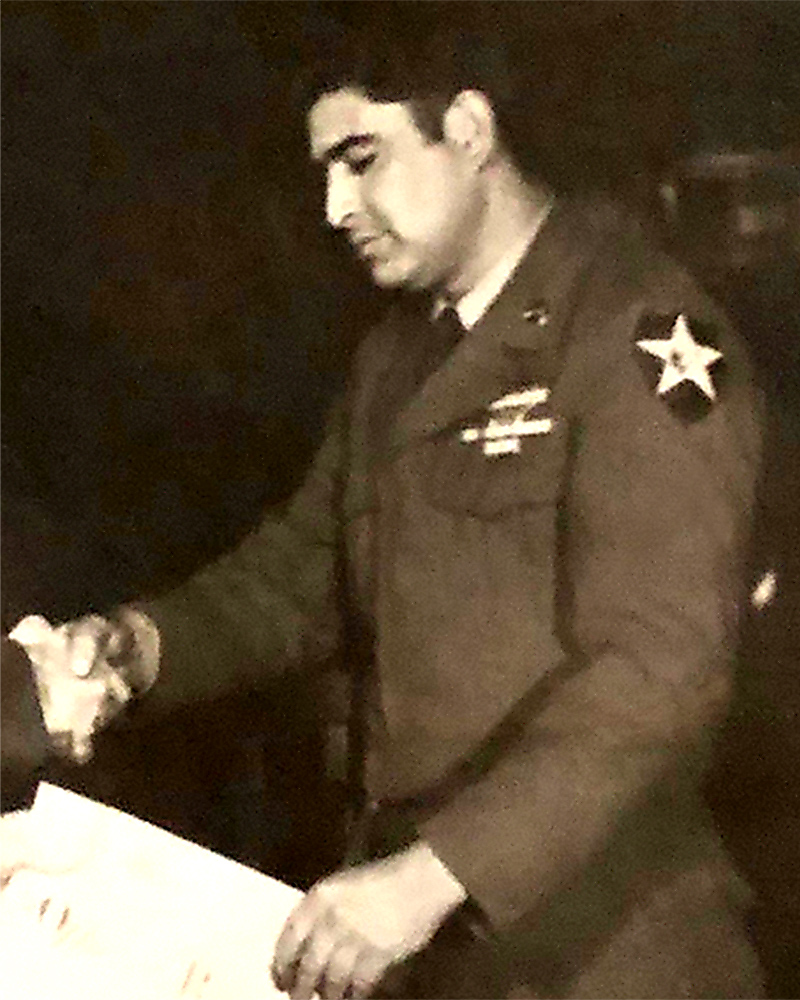

Raul J. Arce

87, El Centro

"Where's my doughnut?"

It was always one of the first questions Raul J. Arce would ask his daughter when she visited him. So she made certain before the three-hour drives from her home in Tustin to his El Centro nursing home to stop at the doughnut shop to pick up a couple of glazed pastries.

"He loved his sweets," recalled Adela Arroyo, Arce's only child.

"He had diabetes, but even when I took him to the doctor, I'd make sure he had some Mexican lollipops to entertain him. The nurses would still ask him: 'Mr. Arce, do you want a lollipop?' I'd be, like, 'I already gave him two!'"

Arroyo's mother, Guadalupe – who was married to Arce for 58 years until her death in 2017 – would bake him pineapple cakes and take tamales or plantains to him at work.

Arce was born in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, and met his wife at a nightclub near the border in Mexicali. She was dancing with another man, but Arce managed to charm her nonetheless, and a month later they wed. They moved to Calexico after obtaining U.S. citizenship.

At first, Arce made ends meet by working in the fields harvesting lettuce, traveling throughout California to find the best crops.

Later, he became a school custodian, a job he held for two decades before retiring.

A devout Jehovah's Witness, he spent most of his free time at church, and enjoyed attending celebrations for those in the community.

"Whenever there was a wedding, he was always the first one dancing," said Arroyo.

Arce was also passionate about table games, particularly dominoes. He and his daughter would spend most of their visits playing with the tiles, the games sometimes stretching on for hours. Sometimes, the "other grandpas and grandmas would join," Arroyo said, because her father had a reputation for being one of the most social residents.

After two employees at his nursing home contracted COVID-19 in March, the disease spread through the facility. Two weeks after contracting the illness, he died on July 9 at age 87.

"He had survived so much -- collapsing twice from diabetes and having to be airlifted to a hospital," Arroyo said.

"The last time I saw him was in February, because then they closed and said we could only see him at the window," she said. "He was just a simple man who liked to play his board games. And who loved his sweets – always."

Arce is survived by his daughter and two granddaughters, Ariana and Alyssa Arroyo.

Desanka Mitrovich

95, San Diego

Thirty years ago, Desanka Mitrovich called her doctor to tell him she wasn’t feeling well. He urged her to call a cab and come to his office immediately, but Mitrovich, ever elegant, ever forceful, dolled herself up and waited for the bus. Only after arriving at the doctor’s office across town did she learn she was having a heart attack.

“Desa was formidable,” said her niece, Milica Mitrovich, “and the doctor still tells that story.”

A fighter to the end, Mitrovich died in San Diego on May 23 due to complications of lymphoma and COVID-19. She was 95.

Born in 1924 in Sveti Stefan, Montenegro (then part of Yugoslavia), Mitrovich was full of fire, grace and wit from the start. As a young woman, she worked as a school teacher in a small mountain village, and later became the mistress of a one-room schoolhouse. She approached her work with a strong sense of duty, and was revered for her firm-but-fair approach to education.

Many of her former students, now adults, still tell stories about how she was a “mean and wonderful” teacher, her niece said, noting that she was just as likely to bring cookies as she was to make them wash behind their ears in the nearby stream.

Mitrovich fought fervently against the Axis’ occupation of Yugoslavia during World War II, and in 1960, moved to San Diego to begin a new chapter of her life. She attended San Diego State University and was the first member of her family to graduate from college. She went on to enjoy a decades-long career at the university’s library, where she worked in the acquisitions department until retirement.

“She was forged in that crucible where women didn’t go off and have their own careers,” her niece said. “The path that she took, being a school teacher and then moving across the world and going to college, required a great deal of backbone.”

Although Mitrovich never married (she said the suitors weren’t up to her standards), she was a loyal friend who made it her “job on the weekends” to call relatives around the world and check in. She was so devoted to her family that when her niece graduated from law school on the East Coast, Mitrovich spent nearly three days on a Greyhound bus to be there.

“If she had to hitchhike or to walk, she would have found a way to do it,” Milica said.

In addition to the friends, relatives and students whose lives she touched, family members said they’d remember her for her poise, charisma, dark sense of humor and beautiful singing voice.

“She was an extraordinary woman,” her niece said. “It was not a conventional life, but it was a life lived as much on her own terms, as much as she possibly could.”

Mitrovich is survived by her sister Beba and four nieces and nephews.

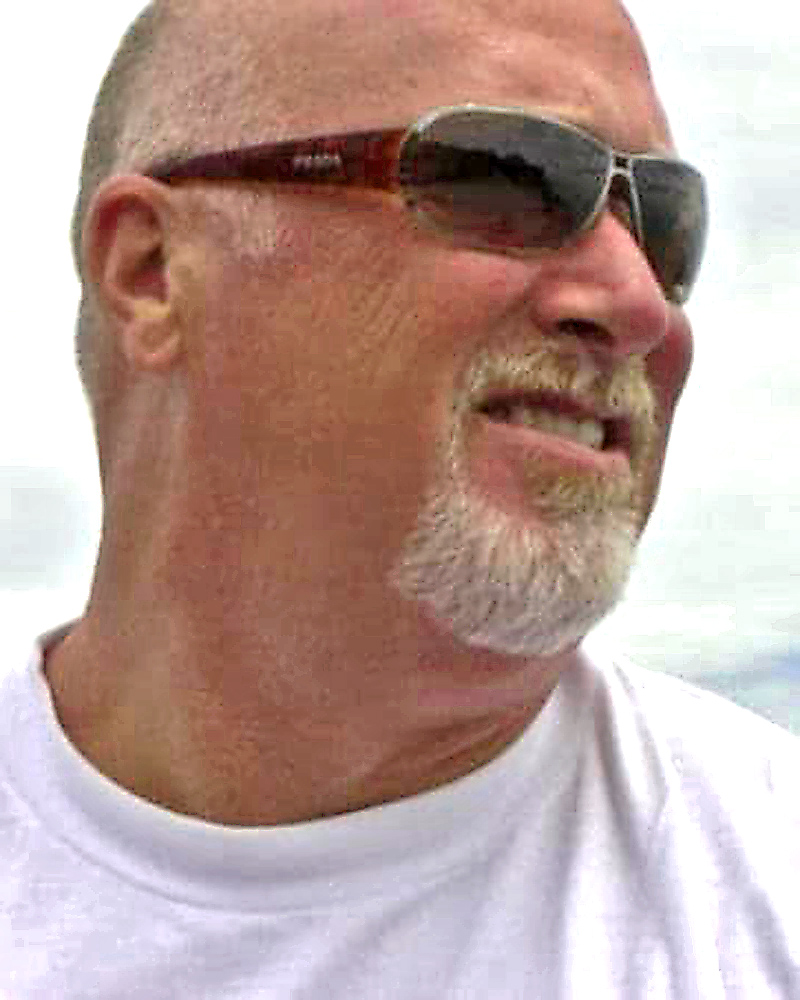

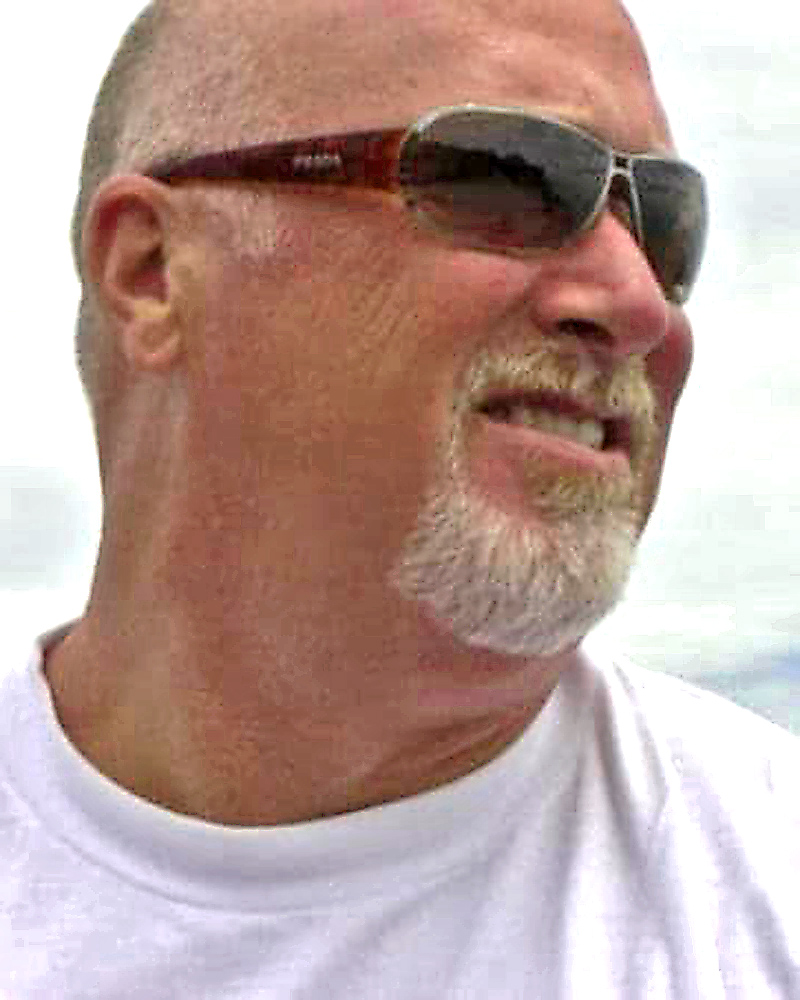

Gary Young

66, Gilroy

Gary Young was a people person. He started conversations with just about everybody he came across — cashiers at the grocery stores, servers at the local breakfast joint.

He had an arsenal of favorite jokes he liked to deploy in these moments. He would introduce himself, shake his new acquaintance’s hand and say, “You better go wash your hands.”

“Why?” the other person would reply.

“Because I just got diagnosed with A-G-E,” Young would say, spelling out the letters.

“He was talking about how old he was,” Young’s daughter Stacey Silva explained, laughing at the memory.

Young’s family believes that his handshaking may have been how he contracted the coronavirus.

“It makes me sad,” Silva said. “But it almost makes me happy at the same time, because my dad was such a loving, friendly, bighearted guy.”

Young died of complications from COVID-19 in an isolation ward at St. Louise Regional Hospital in Gilroy on March 17. He was 66.

Young was in the ICU for 12 days. Because of the infectious nature of the virus, his family was unable to be at his bedside when he died.

The last time Silva saw her dad awake, he signed “I love you” to his family through a set of glass doors.

Young was a retired cabinet maker who worked at Lowe’s Home Improvement during his final years. He was a diabetic and recovered from throat cancer in 2004.

Young lived with Silva in Gilroy. His wife, Melody Young, died of cancer in May 2019. They were married for 47 years.

He is survived by his two children, Silva and Dwayne Young, and six grandchildren.

“Once this all settles down, we’ll have a big memorial,” Silva said. “He had so many friends.”

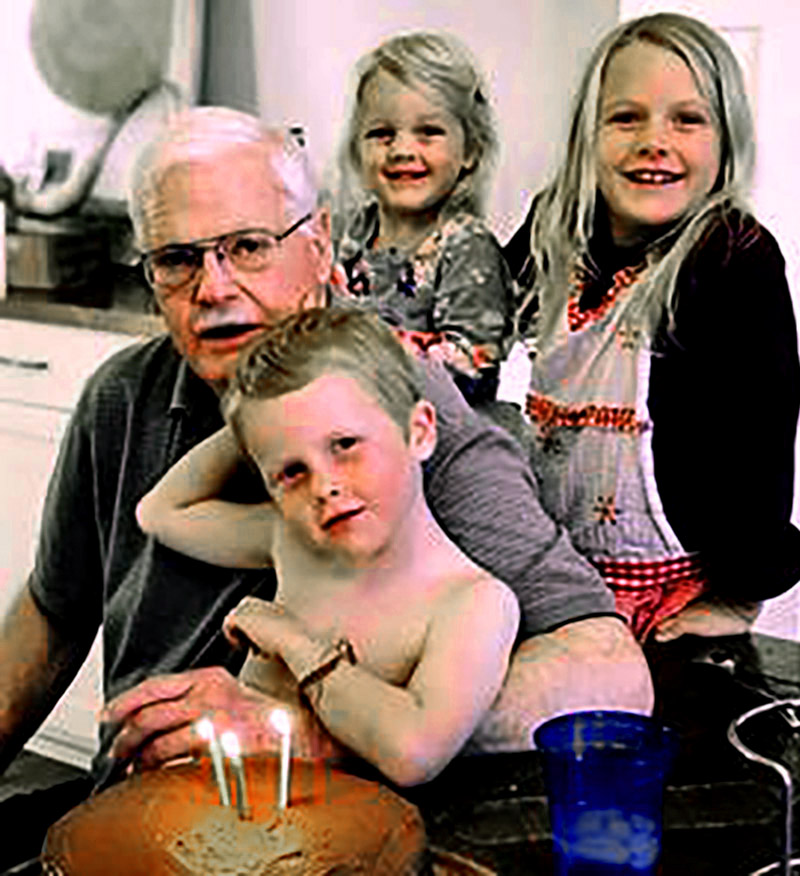

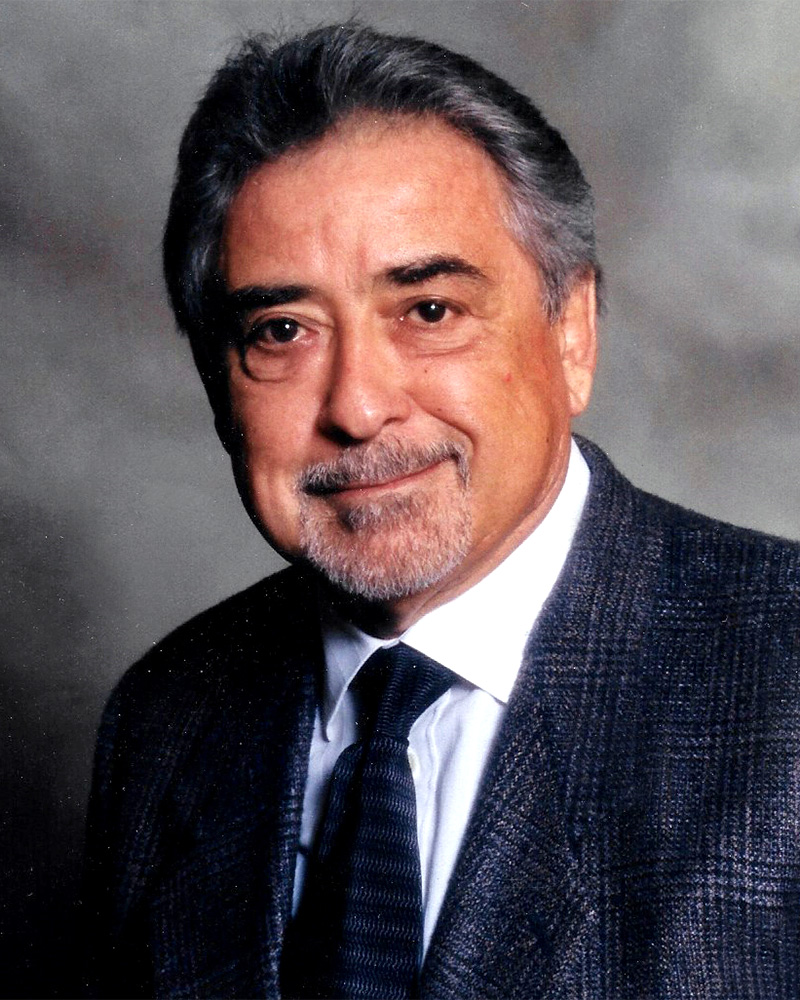

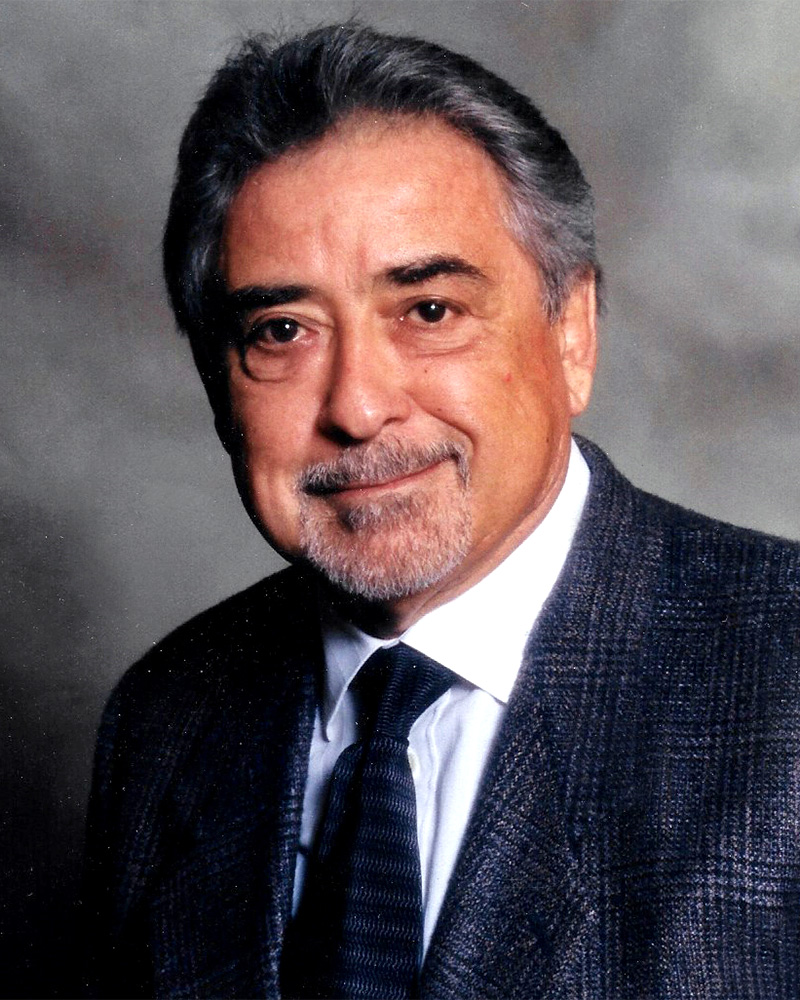

Mike Gotovac

76, Los Angeles

Miljenko “Mike” Gotovac knew a thing or two about Los Angeles. As a bartender at West Hollywood’s iconic restaurant Dan Tana’s for more than 50 years, he was the one constant amid an ever-changing sea of actors, rock stars, barflies and dreamers.

Until his hospitalization on March 16, he remained one of the oldest working bartenders in L.A. He died due to complications of COVID-19 on May 14 at the age of 76.

“Mike was a piece of iron in this city,” said Craig Susser, owner of Craig’s restaurant and Gotovac’s longtime friend. “No matter what happened in your life or what happened in the world, Monday through Friday, he was there.”

Gotovac was born in the village of Lećevica, Croatia, in 1943. As a young man, he joined a wave of Croatians who traveled to Germany to escape the poor economy of what was then Yugoslavia. He landed in L.A. in 1967, where he quickly became part of the city’s tight-knit Croatian community. He became the bartender and resident curmudgeon at Dan Tana’s a year later, but despite his position at the center of the star-studded restaurant, his sons said he couldn’t tell a movie star from a customer off the street.

“He liked old cowboy westerns and he enjoyed sports, so what did he care if you’re an actor or actress in the highest grossing movie of the year?” said his son Domagoj. “That was one of the reasons a lot of these famous people really liked him, because it was really the only time they got treated normal.”

So many customers relied on Gotovac’s steadfast presence that toward the end of his career, he showed up as much for them as he did for himself, his sons said. It wasn’t uncommon for him to bring some of the bar’s customers home for the holidays because they had nowhere else to go.

“There were a lot of lonely people in L.A., and he did have a soft spot,” his son Matija said.

When Gotovac wasn’t at Dan Tana’s, he was the consummate family man. He was a parishioner at St. Anthony Croatian Catholic Church, an avid soccer player and longtime president of San Pedro Croat Soccer Club. His idea of a good time was dinner and dancing with his wife, or doting on his granddaughters, Emelia, Iva and Beatrix, who became his greatest joy.

“He took care of people like nobody else,” said Christian Kneedler, manager of Dan Tana’s. “He really was one of a kind.”

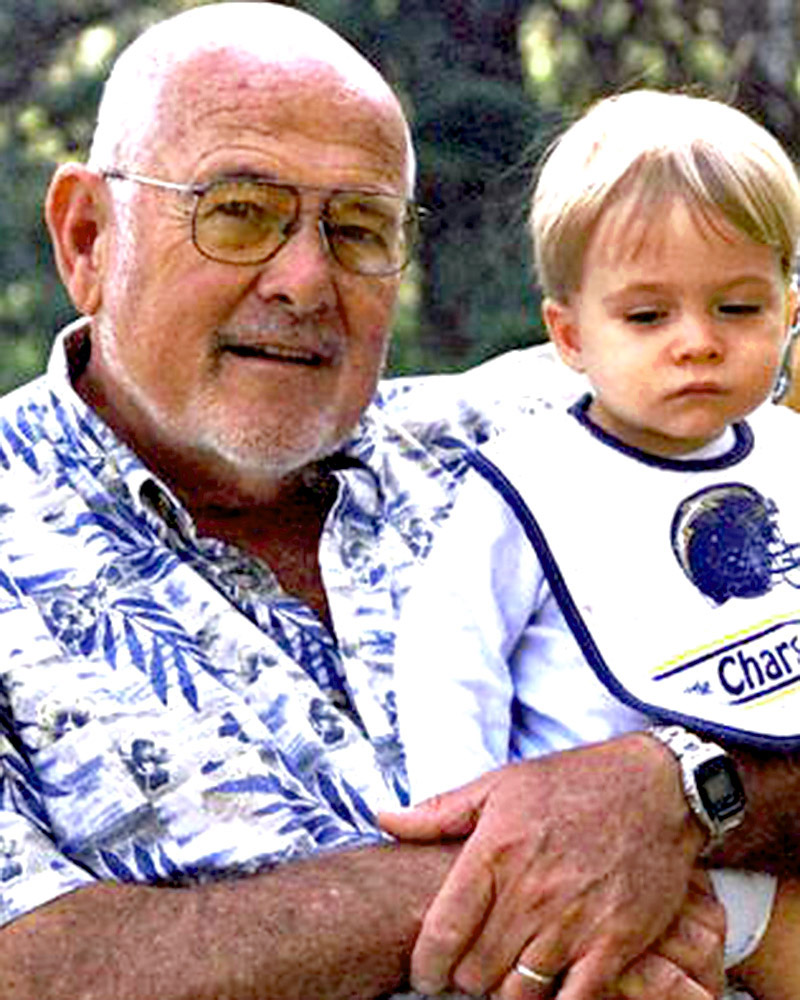

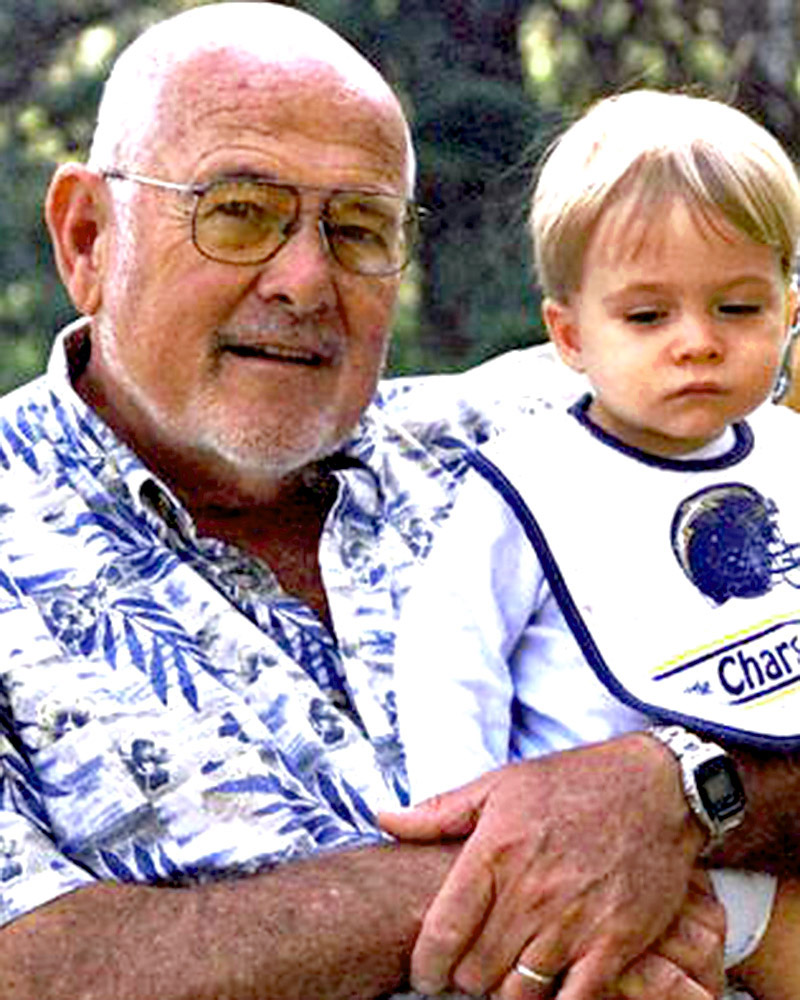

Read the full obituaryRalph Duprey

98, Signal Hill

Well into his 80s, Ralph Duprey could be found biking around his Long Beach neighborhood. Snaking through the streets he had called home for over 70 years on two wheels was calming. It was Duprey's time to collect his thoughts and relax at the end of a long day.

But biking hadn’t always been a peaceful practice for Duprey. As a teenager, he would bike down the Steep Shell Hill in Long Beach.

“I remember him telling me that his bike didn’t have very good brakes,” said Duprey’s son, Mark, “he would get to the top of the hill and it had a pretty good grade.”

“Yes!” chimed in Mark’s sister Karen, “He talked about sticking his foot out and rubbing it against the front tire to slow the bike down. Even at that age, he realized that it wasn’t the brightest idea.”

Duprey’s life began far from the hills and sunny shores of Long Beach. He was born in Canada in 1922 to Thomas and Amada Duprey, the sixth of seven children. Early in his life, his parents decided to head west and landed in California, a place Duprey would come to love.

The family settled in Long Beach and lived in a small three-bedroom house. Duprey ended his days just a few blocks from that house — at St. Mary’s Hospital, Long Beach where he died on April 18 from complications related to Covid-19. He was 98.

Duprey celebrated his birthday just three weeks before his death. While his children were unable to be in the same room due to coronavirus restrictions, they improvised and found a creative way to share their love.

The three children, Mark, Karen and Arlene stood outside his assisted living facility in front of a big window that faces the street. Karen brought along a chalkboard.

“We were writing messages and wearing crazy hats,” said Mark, “we looked like idiots but dad got a big kick out of it, he was laughing and smiling.”

The separation instigated by coronavirus was particularly difficult for the family, who loved spending time together with their father. “Mark and I would split the time” said Karen, “between us we were usually there six nights a week.”

They would bring their dad his favorite food ... chocolate. “We would take him chocolate malts, or Hershey bars.” said Mark, “but he just really loved any chocolate, and I mean, he loved chocolate.”

Nurses at Duprey’s assisted living facility encouraged the children to bring their father healthier treats, for fear of the almost 100 year old man developing diabetes. But, he was fit and trim until the end.

Duprey’s confidence in his own physical ability was built on years of working in plumbing and construction, skills he began to develop during WWII. After graduating from Long Beach Polytechnic in 1941, Duprey joined the Coast Guard and served as a motor machinist mate during the war.

Upon returning home, he became a union plumber, working on new buildings in and around Long Beach. He was also comfortable with most parts of construction work and put his skills to good use around the family home.

“He was fixing things like the furnace under the house well into his 80s,” said Karen, “we practically had to drag him out of there!”

“He just never moved like an old man” said Karen, “No, he was spry and graceful” added Arlene.

Duprey’s physical grace was also apparent when he danced. “We would have parties at the house,” said Karen, “there was usually dancing, and mom and dad would also go out on dates to go dancing.”

Duprey met his wife, Mary Lee Smith after WWII and the couple married in 1948 and the couple were together until her death in 1987 at the age of 60. “It was a pretty tough time for about a year,” said Mark, “but dad came out on the other side.”

The children knew Duprey was beginning to heal when he got back on his bike. “I remember him riding along Newport Ave. he actually rode the bike half the length of the block backwards,” said Mark, “he wanted to prove to himself that he could still do it — and he was satisfied.”

Ralph Duprey is survived by his three children, eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Ever A. Linares

45, Los Angeles

Even while suffering from fever and body aches, Ever A. Linares kept working by phone the week before Thanksgiving to connect needy families with turkeys for the holiday.

By Nov. 30, Linares, a 45-year-old gang intervention worker who quelled violence in different parts of the city for more than a decade, was dead from complications of COVID-19, his wife Andrea said.

The co-founder of Resilient, a nonprofit organization that works with at-risk and gang-involved youth, Linares was known locally for working to reduce violence. In addition to running his own agency, he worked with the Mayor’s Office of Gang Intervention and Youth Development program to train intervention workers and police officers. He also traveled the nation to train community workers with the Urban Peace Institute, a group that works to reduce street violence.

“It was his mission to show young people across the city the power of faith, of hope and of love in the face of violence and poverty,” L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti said.

Born and raised in Los Angeles’ Pico-Union neighborhood, Linares got involved in gangs by the time he was 13, his wife said. When he reached his 20s and had his first daughter, he began transitioning away from gangs and toward church.

“He mentioned that he wanted something different, a different life for his daughter,” his wife said.

He became involved in Victory Outreach Ministries and eventually began working with different gang intervention agencies across the city.

“People would just gravitate toward him,” said Fernando Rejón, the executive director of the Urban Peace Institute.

This year, amid the pandemic and a rising homicide rate, Linares kept working to help families. His organization handed out personal protective equipment in the South Park neighborhood where the agency is based and held weekly food drives.

Sometimes, his devotion to his work would wear on his wife. One night years ago, Linares was eating dinner with his family when his phone rang. Andrea said she shot him a look, annoyed that their meal was going to be interrupted yet again.

It was a person in crisis. Linares told him: “Do not make a permanent decision based off a temporary feeling.” Andrea said that encounter helped her better understand her husband’s work.

“What if he didn’t pick up the phone call?" she said. “He prevented somebody from probably going to jail.”

Linares said her husband was a patient man. If a person needed a job and didn’t know how to fill out the application, he would sit and walk them through the process. In addition, he would take the time to tell those he helped what it means to be presentable and what employers want to see.

Like many of the city’s intervention workers, Linares wanted to contribute to making peace on the streets. Even as a youth leader in church, he connected with others who were in need, recalled longtime friend and co-founder of Resilient, Michael Guedel.

Guedel said he came to see Linares as a mentor over the years.

“He would always tell me never to be paralyzed by fear but to keep moving,” Guedel said.

Linares is survived by his wife, seven children and one grandchild.

Barbara Johnson Hopper

81, Oakland

Barbara Johnson Hopper was known for giving friends and family plum jam made with fruit picked from her yard.

Her garden — full of lemons, vegetables, and flowers — offered her a refuge when she was worried and needed to pray to God, said her daughter, Adriane Hopper Williams.

“That’s what she would always say, ‘I’ve got to go to the Earth,’” Hopper Williams said. “That was her way of just getting centered.”

Hopper, 81, died of the effects of COVID-19 on March 26 after spending five days in the hospital. Hopper Williams said her family closely follows the news, and she remembered discussing the coronavirus outbreak with her mother, thinking it wouldn’t hit as close to home as it did.

“We’re still, every night, watching this news and she’s now one of those numbers,” Hopper Williams said.

Hopper was funny, gregarious, and “the ultimate producer,” her daughter said.

“She’s the one that brought people together and knew how to inspire people toward a purpose,” Hopper Williams said. “She just knew how to talk to people and to get them back on track to what really matters.”

Hopper was born in Milwaukee and studied social work at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. In 1960 she met her husband, Dr. Cornelius Hopper, while he was completing his residency at Milwaukee County Hospital. Cornelius fell in love with Barbara, as well as his future mother-in-law’s soul food cooking. Barbara and Cornelius wed in 1964.

When the family moved to Alabama in 1971 for her husband’s new position as medical director of the John Andrew Hospital at Tuskegee Institute, Hopper started the Tuskegee Laboratory and Learning Center, an alternative school, as well as a real estate business.

In 1979 the family moved to the Bay Area and settled in Oakland, where she continued to work as a real estate agent while also founding and participating in community groups, and serving on scholarship boards for medical students. At Church by the Side of the Road, which she attended with her family, she led a yearlong reading of the Bible that ended with a trip to Jerusalem.

She is survived by her husband of 55 years, Cornelius, her two sons Michael and Brian, her daughter, Adriane, and two grandchildren.

“I know we’re all biased, but for me personally, when I think about a woman of character, integrity, strength, beauty, grace, wisdom, and charity, that is who I think of,” Hopper Williams said. “She is my role model.”

Jennifer Gibbs, 67, said she met Hopper through a mutual friend 13 years ago. Whenever Gibbs was sick, Hopper would bring her chicken soup. When Gibbs drove to Ohio to pack up her 93-year-old mother to move in with her in the Bay Area, Hopper told her she’d have dinner waiting for them when they arrived.

One of the bridge groups Hopper organized had a Zoom meeting to share how they felt about her after they learned of her death, Gibbs said. “She was the one,” Gibbs said, “that brought us all together and kind of was the glue.”

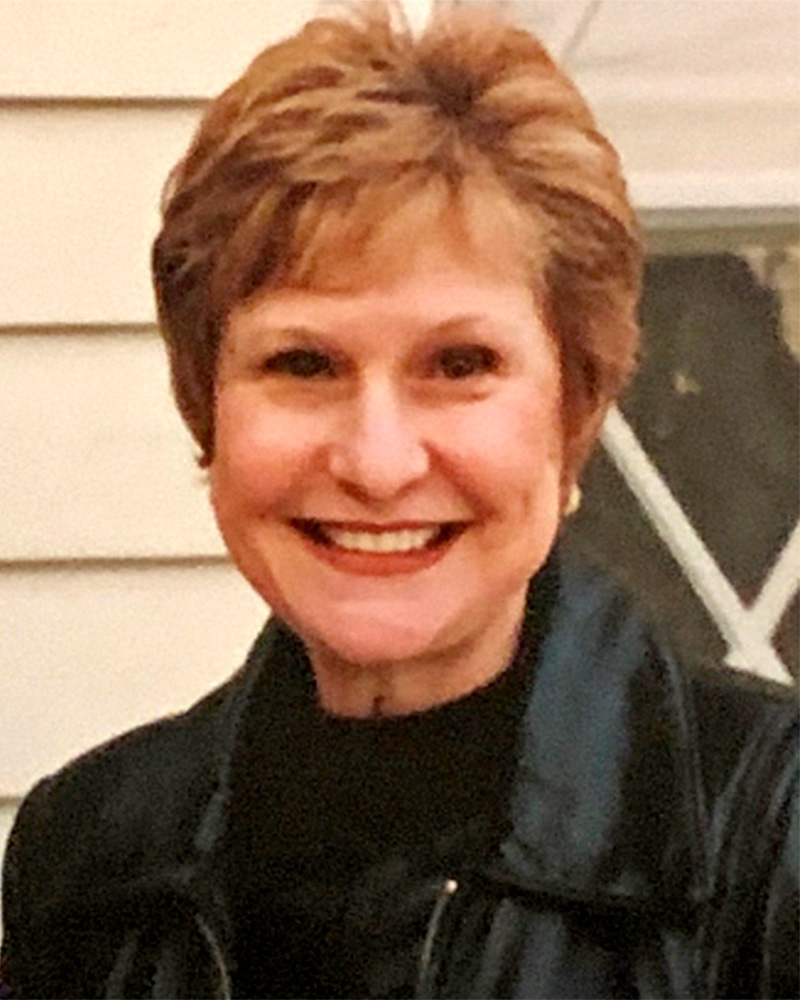

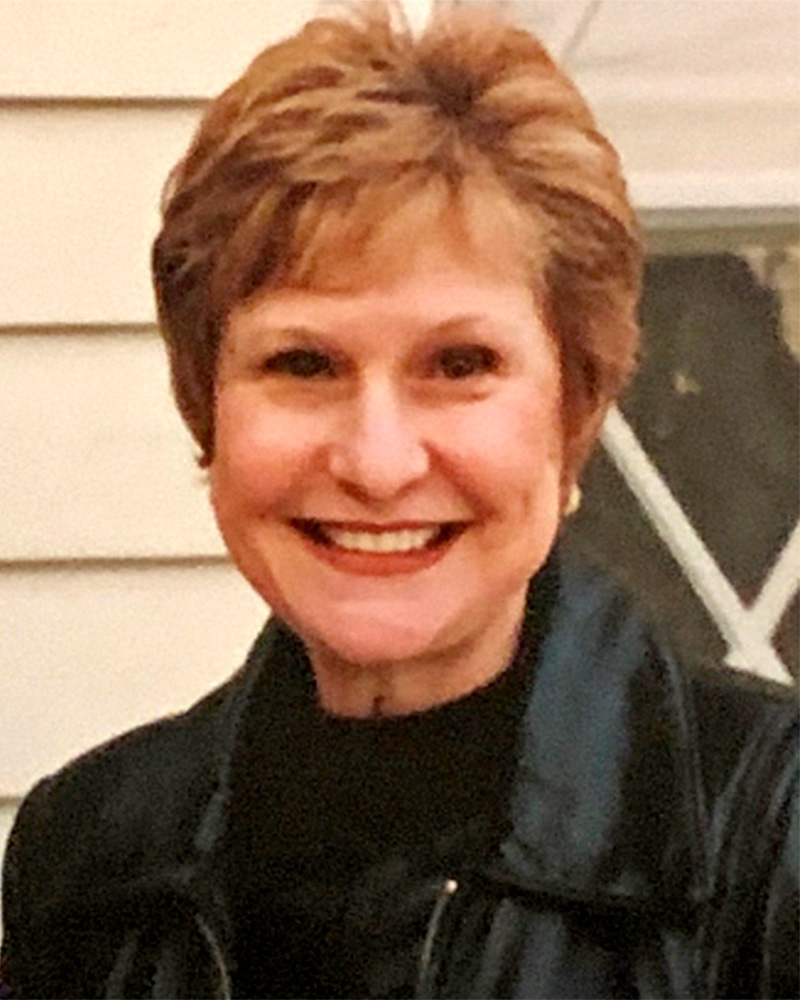

Ronda Felder

60, San Diego

Ronda Felder gave her life to people in need, always doing whatever it took to make room in her home, her heart and her family for anyone who was hurting, lost or abandoned.

A social worker for the County of San Diego, Felder died Aug. 3 at Kaiser Permanente San Diego Medical Center, where she had been battling COVID-19 for a month. She was 60.

One of Felder’s two daughters, Treasure Felder, said her mother leaves behind a legacy of love and service, something she showed not just to her own daughters, Treasure Felder and Chomedy Curry but to the dozens of foster children she helped raise, her church family at New Creation Church of San Diego, her relatives, the children she watched over as a social worker and anyone else in need.

“She was all about her family, those related to her by blood and those related to her by love,” said Treasure.

When Treasure was in middle school, her mom would take in her classmates and friends “whose moms weren’t doing OK,” sharing with them her family’s modest home and resources.

“Even though we didn’t have a lot she always made space,” Treasure said. “Sometimes we were all sleeping on top of each other, but we had a home.”

Felder was constantly on the move, always working to improve life for others, never slowing down, rarely getting exhausted, almost never getting sick, Treasure said. As a single mother, she worked full time after the family moved from New York to San Diego in 1998. She began pursuing a college education in 2003, graduating from San Diego State University with a degree in social work.

Ronda Felder graduated from San Diego State University in 2009 with a bachelor’s degree in social work.

“She’d go to work at 5 a.m., work eight hours, come home, make sure we had what we needed and then she would go to school,” Treasure said. “She’d come home late and do it all over again, every day for years.”

Once Ronda Felder graduated from college at the age of 50, she did not slow down, Treasure said. She got a job as a social worker for the county, and worked tirelessly for the children on her list, even after the pandemic descended on California. First she visited them on video chat services, then, when the county directed social workers to resume visiting children, in person.

Treasure said her mother felt her work was a calling, and she answered the call even though she knew she was putting her life in danger with every in-person visit amid the pandemic.

“She knew the risk, but in many ways, she thought she was protected by God because she was doing God’s work,” Treasure said.

She is survived by her mother, sister, children and grandchildren.

Carol van Zalingen

53, Sylmar

Carol van Zalingen fell in love with Southern California when she moved to the Los Angeles area in 2008 to take a job teaching English at the private Westridge School for Girls in Pasadena.

“She said she would never live anywhere else – it was a real ‘Harry Potter finds his Hogwarts’ moment for her,” her brother Michael van Zalingen said.

Carol, 53, died of complications related to the virus on April 14.

Carol’s affinity for the area stemmed in large part from her work at Westridge, where students referred to her affectionately as “Ms. V,” her brother said.

In 2015, she became dean of student support for its lower and middle schools. Carol earned a reputation at Westridge for helping girls reach their fullest potential and for her “seemingly bottomless capacity for empathy and caring,” according to an online tribute posted by colleagues and students after news spread of her death.

“She never wanted a light shined in her direction, but her ability to listen, to be present, and hold time and space for students and friends was uncanny,” the tribute said.

Michael van Zalingen says his sister possessed an introverted yet open-hearted nature from an early age.

He remembers her not only as generous, patient and “the smartest person I ever knew,” but also as someone who was devoted to her students and the welfare of animals. She lived in Sylmar with two dogs.

“She was a compulsive dog rescuer,” he said. “Every time she saw a stray dog, her heart would melt.”

The siblings’ lives were unsettled early on because the family moved frequently. Their late father Frederik van Zalingen, a native of the Netherlands, was an international banker who received a different post every three years.

Carol was born in Kampala, Uganda, and Michael in Tehran.

By the time Carol was 6 and Michael was 3, their American-born mother had grown weary of what Michael describes as their “peripatetic” lifestyle.

“So we got visas to come to the U.S.,” he said. They lived in the Midwest and South.

Earlier in her career, Carol worked as a teacher in Alabama and Ohio.

Michael said he intends to honor his sister by granting her final wish — to have her ashes buried in Scotland.

George Chiu

86, Palo Alto

George Chiu was a craftsman with an eye for detail and a passion for problem solving. He carried both traits with him throughout his life.

Chiu, a San Francisco Bay Area native with a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from San Jose State, began his career at Fairchild Semiconductor. In 1968 he followed Fairchild colleagues Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore to a start-up the two had founded in the semiconductor chip industry.

The 39th employee at Intel Corp., Chiu spent most of his career designing and assembling “packaging” that would seal off semiconductor chips from moisture and other contaminants while still allowing the transmission of electronic signals.

“He was always a real hands-on engineer,” said his daughter Jenny Sears. “They just had to be inventive back then — there was no class in semiconductor chip packaging. They’d be testing materials all the time. People would say, ‘Well, your dad knew more about materials than some people with doctorates.’”

In a company publication celebrating Intel’s 25th anniversary, Chiu reflected on his career: “I was the first engineer doing package development at Intel. I’m still doing basically the same thing and I love it,” he said. “I can hold a product in my hand and see my contribution to it; my identity’s in that package. I was supposed to retire almost 10 years ago, but when there’s so much going on here, who wants to retire?”

In the 1990s Chiu also worked on a technology, widely used today, known as “C4” processing that enabled chips to simultaneously make hundreds, and eventually thousands, of electrical connections.

Craig Noke, a former carpool mate and jogging partner, said Chiu loved to solve problems.

“That was his life,” Noke said. “You had some problem at work, and try and find out what the solution is — that was his satisfaction.”

Chiu had an eye for handiwork as well. When he had his house remodeled, he came home every day and inspected the work, asking the contractor to straighten something out “1/16th of an inch” even if functionally it was perfect, said Noke, who used the same contractor.

Chiu had a lighter side, too. Colleagues and his daughter recalled his penchant for rock concerts at the Fillmore in the 1960s, where he would stand next to speakers to immerse himself in the music — a habit that may have contributed to his severe hearing loss.

“He was like this old hippie,” Sears said.

Chiu had a plethora of hobbies — travel, photography, jewelry making, collecting tools. He liked cars, buying a Porsche Boxster after he retired.

Most of all, though, he loved to eat — Chinese food, especially.

Paul Engel, a colleague and best friend of 40 years, spent months with Chiu in Penang, Malaysia, where Intel had package assembly plants. The two would go on culinary adventures, often seeking out char quay teow, a Chinese noodle-and-seafood dish.

“We couldn’t get enough of that,” Engel said.

Engel later left the company but continued to meet Chiu every week for years.

“We’d go to lunch and eat like pigs — and he’d go home that evening and right away ask, ‘What’s for dinner, Florence?’” Engel said, referring to Chiu’s wife, who died in 2011.

When Chiu died, friends joked that he went to heaven, found Florence and immediately asked, “What’s for dinner?”

Late in life, Chiu developed Alzheimer’s disease. He continued to live alone at his Palo Alto home, assisted by round-the-clock caregivers. By late last year much of his memory was failing, but Engel said “he could still talk about Penang and the food there.”

It’s not clear how Chiu contracted COVID-19, but his daughter said it could have been from a recent hospital stay or possibly from one of his caregivers, although they were extremely careful. He died Dec. 31.

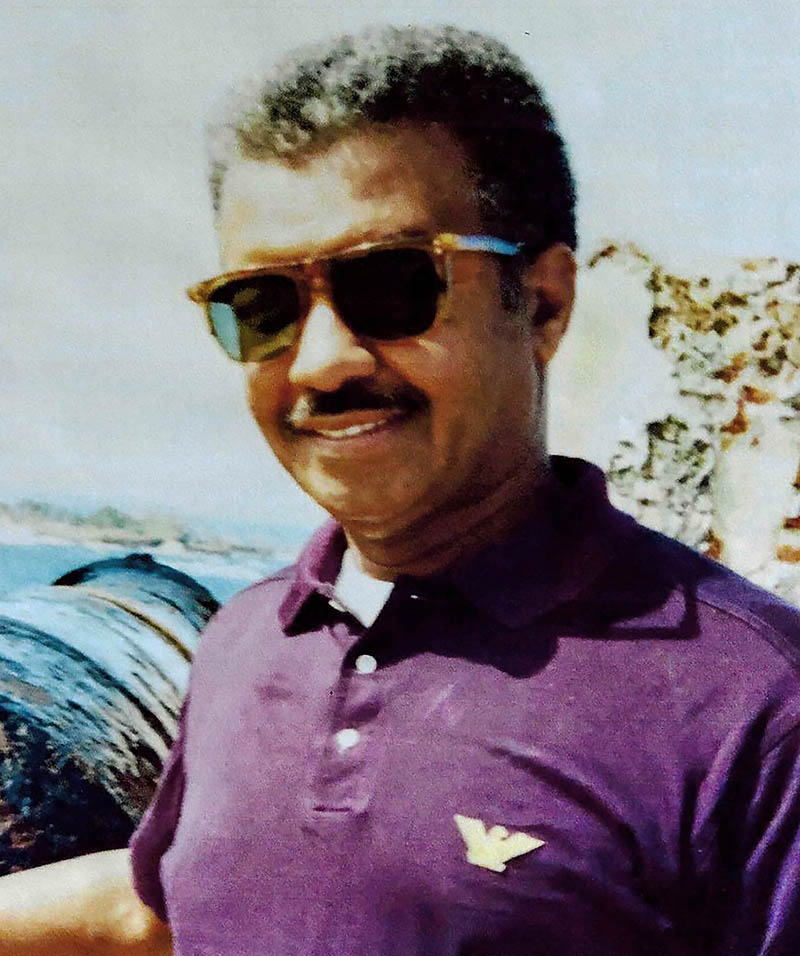

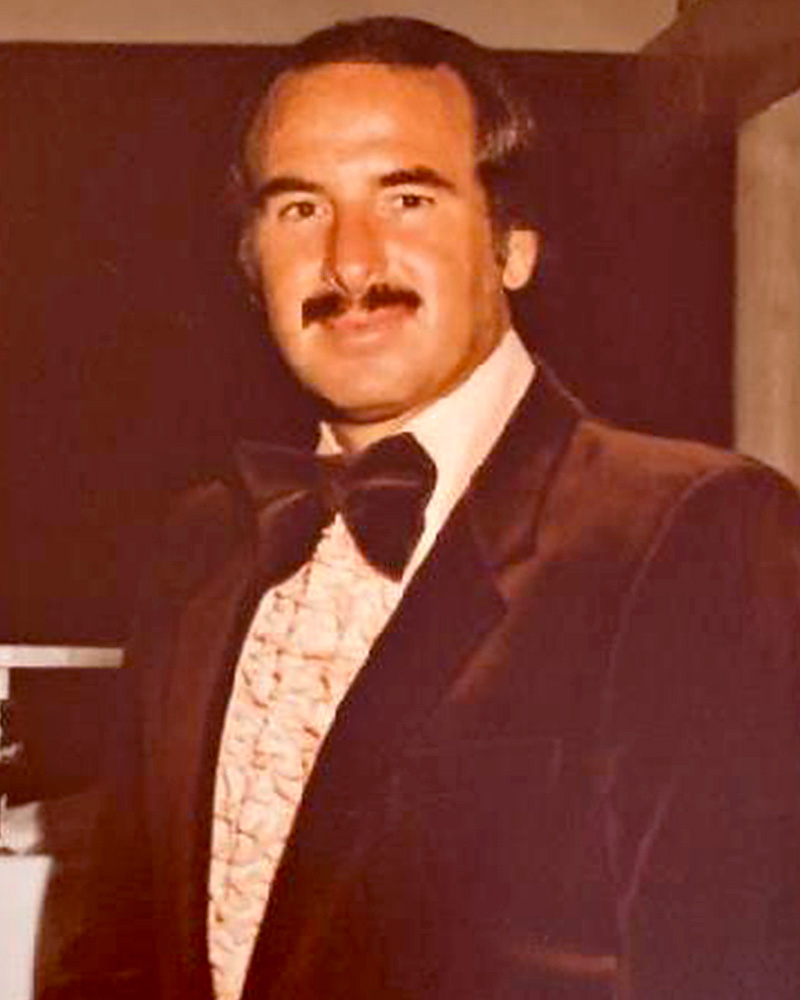

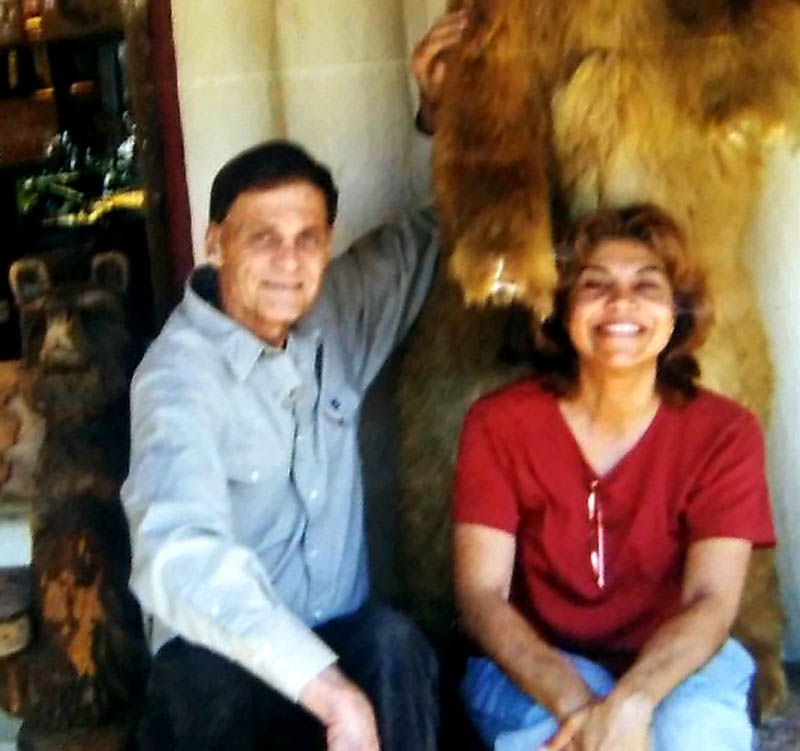

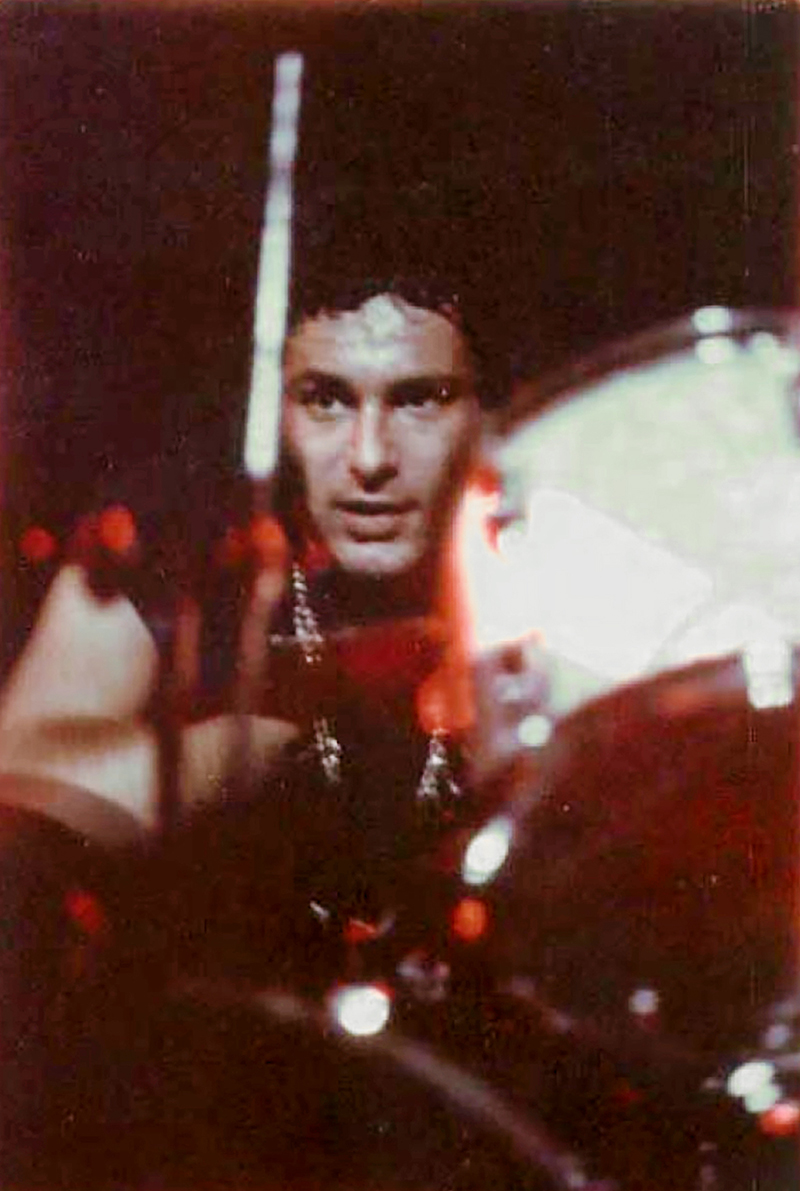

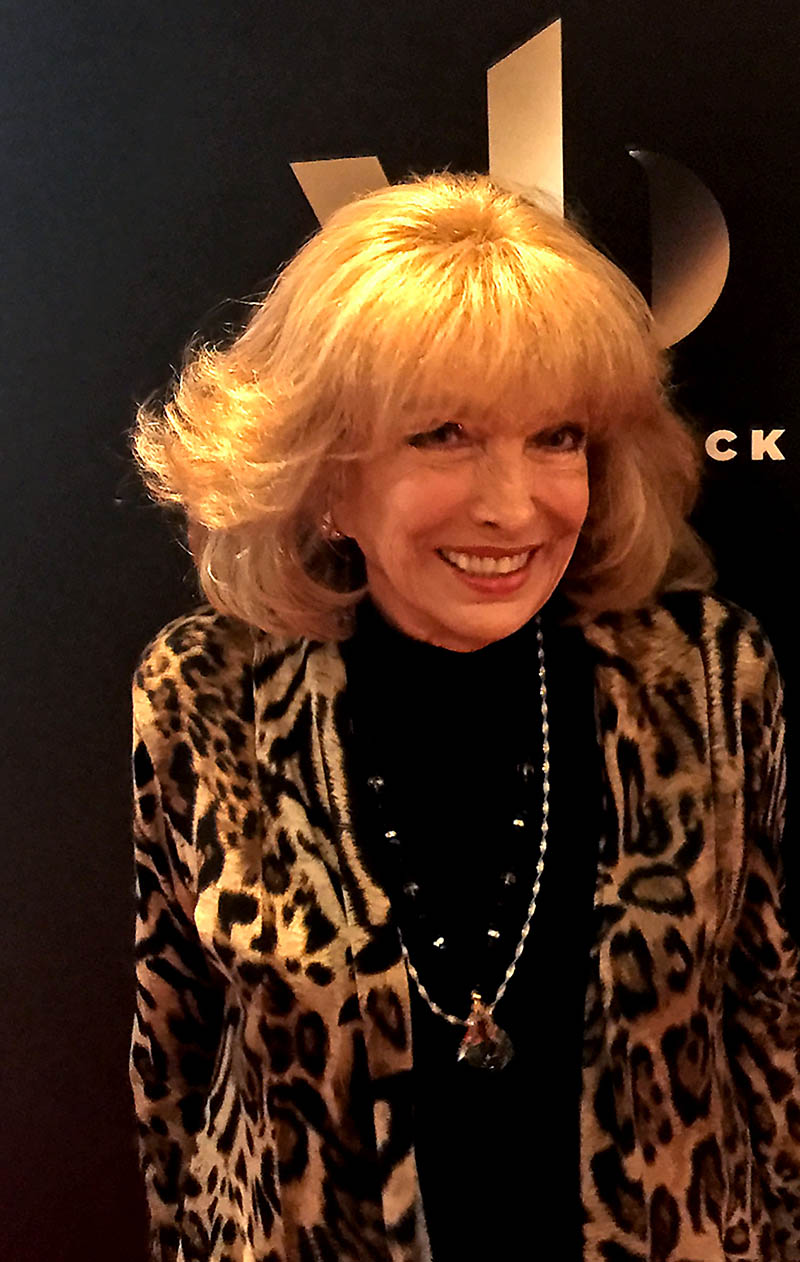

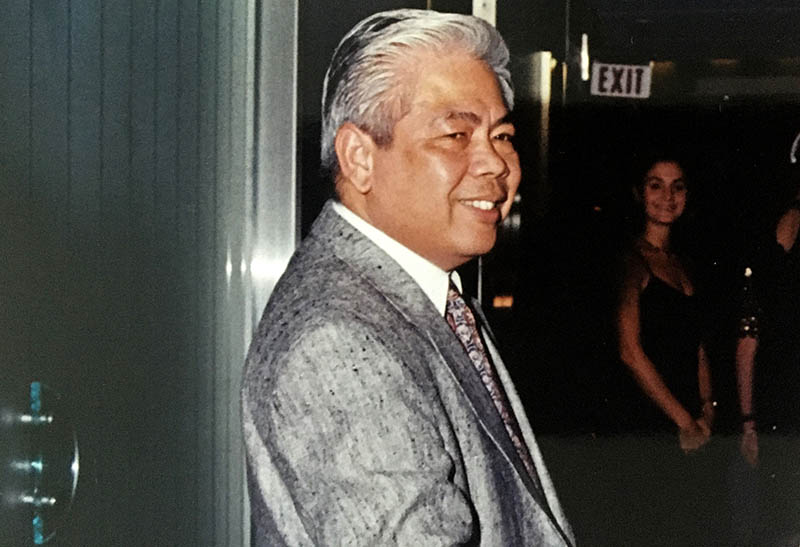

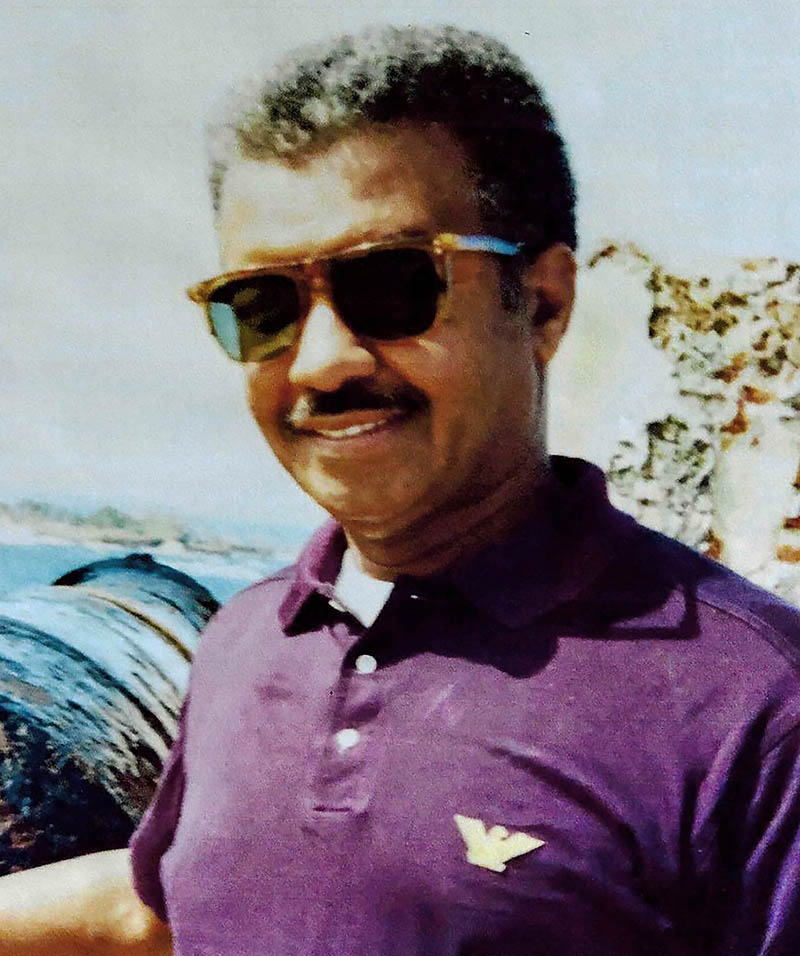

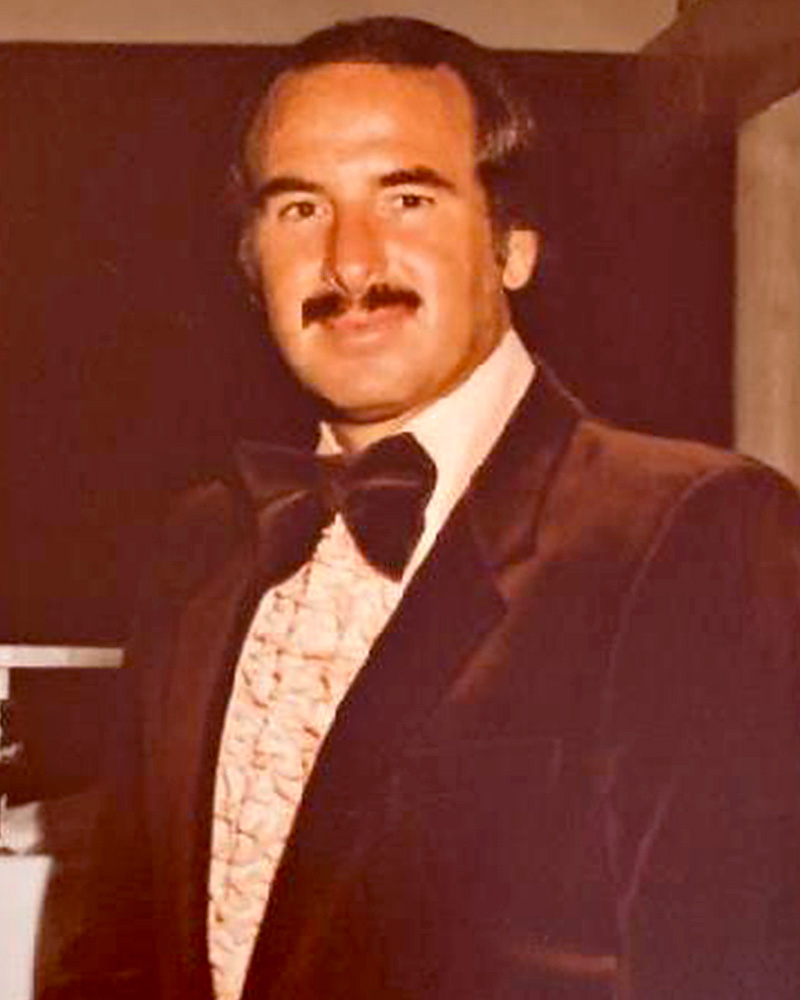

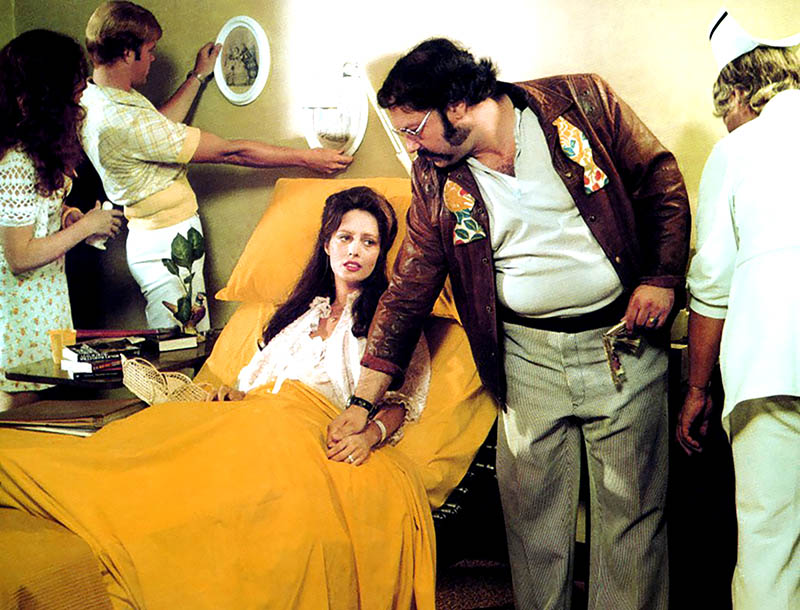

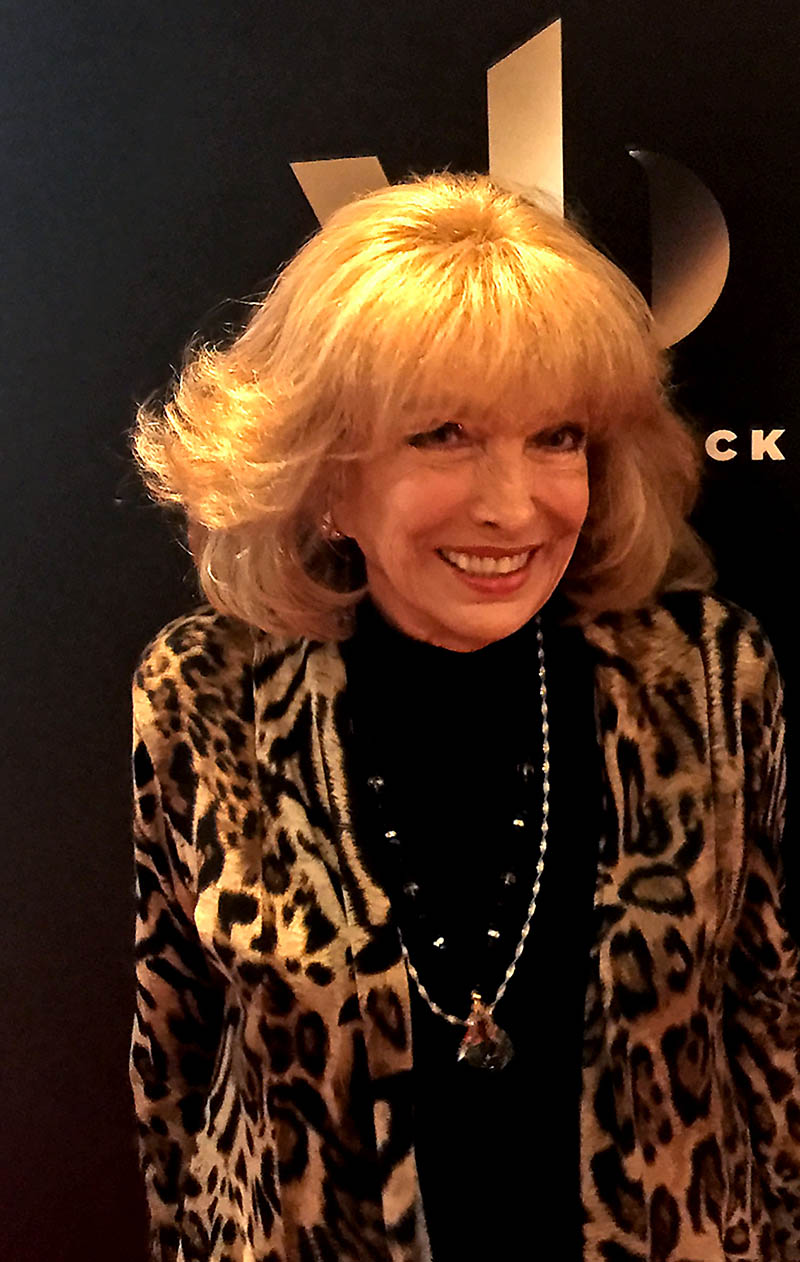

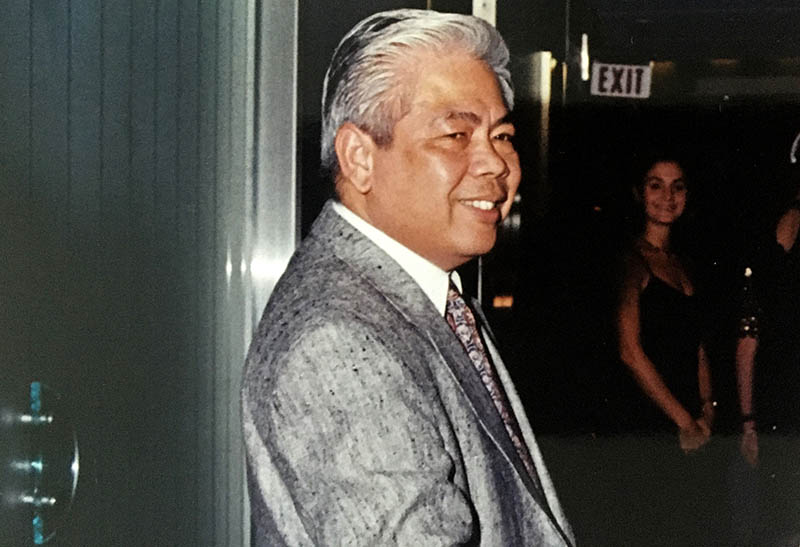

Ronald Harris

82, Los Angeles

If you were fortunate enough to meet Ronald Harris in the late 1970s, you likely had to answer two questions: What would you like to drink, and where you would like to go?

The larger-than-life luxury travel agent, renowned as much for his charisma as for his eye-popping global excursions, died Aug. 5 from complications of COVID-19. He was 82.

Harris was born in Los Angeles in 1938. His mother was an aspiring vaudeville singer, and his father a pioneer of the tourism industry who traveled on steamships. Harris had a happy childhood of surfing, skiing and outdoor adventures, and he graduated from Loyola High School.

After his father died, Harris took over the family business and eventually went on to co-found Hemphill Harris Travel, a premiere travel agency. His passion, his family said, was Travel with a capital “T.”

To him, there was no limit between cultures and countries,” said his son-in-law, Daniel Franco. “There were no boundaries. Anything was possible.”

Harris’s custom tours — fantasias of elephants and exotic dancers, flashy sports cars and French river boats, African trains and jumbo jets reimagined as flying piano bars — were enough to garner a 1986 write-up in the Los Angeles Times, which dubbed them a “first-class spectacle” designed for “the rich and the restless.” A single ticket could cost upwards of $23,000.

The trips were incredible feats of resourcefulness in a pre-Internet era, his children said, and were often only feasible because Harris himself had done them first.

“He was definitely a visionary,” said his daughter Marissa. “He had this drive to make things different, fun and exciting.”

And although the agency commanded much of Harris’s energy, he also made time for his family. He enjoyed taking his children camping (or “glamping,” Marissa said) and pushed them to try new foods and experiences. He also encouraged them to take an interest in the travel business.

“I felt so fortunate that he exposed me to different things,” said his son, Marc, who worked with his father for several years. “To go to Africa on safari when I was 10 years old was just mind blowing.”

A longtime member of the Traveler’s Century Club — a club for people who have been to at least 100 countries — Harris also kept a baby crocodile and a pet piranha in his office that were meant to encourage visitors to “dream more,” his children said.

“He would always say, ‘If the why is important enough, you’ll figure out the how,’” Franco said. “His ‘why’ was to make it incredible. He wanted to outdo what anyone else had experienced in the world.”

And although Hemphill Harris folded after a disastrous sale to Weststar, Inc., in 1989, it wasn’t enough to dampen Harris’s spirit. He went on to found another travel agency with his second wife, Sylvia, and also made time for two of his other passions: fishing and golf.