Vainiaku Magic Na’a walked into a Scheels sporting goods store south of Salt Lake City on a September afternoon in 2021. He strode past racks of camping supplies and the indoor Ferris wheel and headed upstairs to the expansive gun section.

He picked out a Glock 43 pistol from one of several locked display cases set amid a taxidermied menagerie, according to a federal criminal complaint. He showed the clerk his Utah driver’s license and concealed-carry permit and checked “yes” on the required federal form that asked whether he was purchasing the gun for himself.

Then Na’a drove to the nearby home of his uncle Siosifa Lavulavu and handed him the Glock in exchange for the cost of the gun, $529.99, plus his $100 fee for making the buy, the complaint said.

Federal prosecutors accused Na’a of buying at least 97 firearms from dealers in the Salt Lake City area between September 2019 and February 2022, each time attesting the guns were for himself. He and his uncle allegedly passed many of these guns along to an Oakland father-and-sons operation that sold them in California. Often, the weapons ended up in criminals’ hands.

When Na’a bought the guns, he broke the law by providing false information on a federal form, according to the federal indictment against him. In 2022, a new federal law made the act of illicitly buying guns for someone else a crime called a straw purchase. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives has identified straw purchases as among the most common firearms trafficking pathways. They’re also one of the hardest problems in gun regulation to solve.

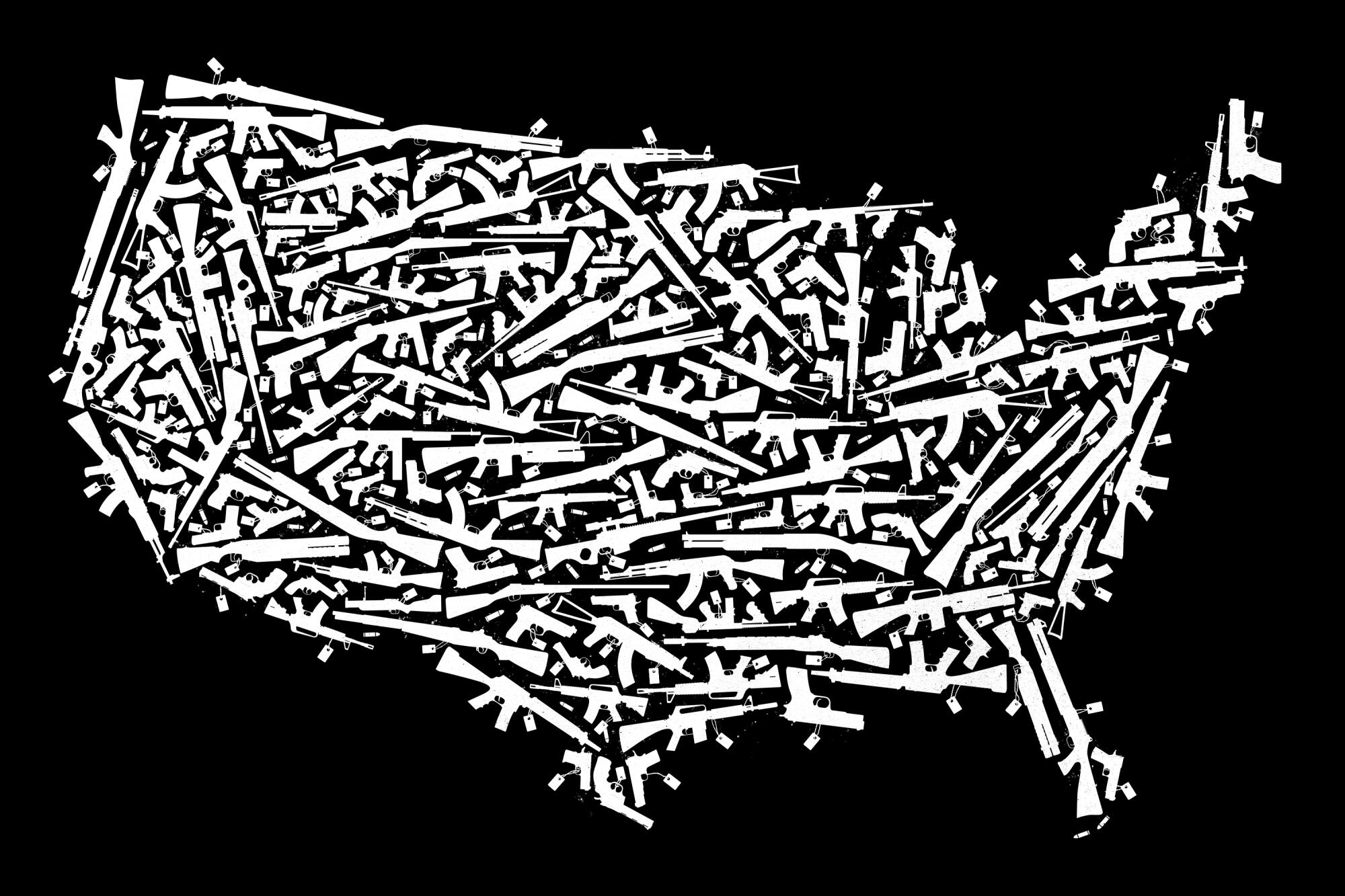

Most Americans live within 10 minutes of a gun store. The Los Angeles Times set out to determine whether easy availability is a key driver of gun violence — but it’s not that simple. This series explores the complex relationship between firearm access and gun crime.

American civilians own an estimated 352 million firearms and demand for guns reached record levels in 2020, as measured by background check data. In exploring gun access in the U.S., The Times interviewed more than 100 people, obtained volumes of public records, reviewed thousands of pages of court filings and law enforcement records, and analyzed millions of rows of federal, state and local data.

The Times analysis found that there’s a firearms dealer within a 10-minute drive of 88% of the U.S. population, and layers of regulations have not stemmed the flow of guns to criminals.

When law enforcement agencies recover a gun, they can ask the ATF to track its purchase history. These traces are a key tool to understand firearms trafficking patterns. Over the last decade, the number recovered and traced annually has steadily increased, according to data The Times compiled from ATF reports, and these guns are moving more quickly from store shelves to crime scenes.

As Michael Eberhardt, former chief of the ATF’s firearms operations division, noted, most firearms used in crimes enter the market through licensed dealers. According to the ATF, a short amount of time from purchase to recovery can be an indication of gun trafficking. In 2022, California law enforcement agencies recovered 5,540 guns within a year of their sale by a dealer, more than triple the number recovered in 2012.

Despite the clear pipeline from straw purchases to street crime, federal authorities say it’s difficult to make any headway against the practice, or even to know how much of a problem it is. Even for agents with cutting-edge tracking tools, investigating straw purchases is a complicated and time-consuming process.

To prove Na’a knowingly deceived a firearms dealer, investigators monitored his cellphone and car and traced his gun purchases, according to the complaint. To show he was dealing without a license, they reviewed text messages, bank records, recent earnings and transactions on money transfer apps.

“Trying to identify straw purchases is extremely, extremely difficult,” said Rick Vasquez, who ran the ATF’s firearms trafficking and interdiction branch until 2014.

But for a straw purchaser, buying a gun is as easy as checking a box.

From the gun store to the street

Lavulavu began the text exchange casually.

Then he got right down to business, according to cellphone records included in the criminal complaint against him, using shorthand to request two models of handgun.

After a couple more texts, he sent Na’a photos of $100 bills. Na’a asked if Lavulavu knew what model of Glock he wanted.

Next, Na’a sent a photo of a credit card machine at the Scheels sporting goods store in Sandy, Utah. Two items were listed on the screen: an FN Five-seveN semiautomatic pistol and a Glock 43X handgun.

Mission accomplished.

Utah is considered one of the gun-friendliest states in the U.S. It has a state firearm, the Browning M1911, to honor the Ogden-born founder of the iconic gun manufacturer.

“It’s easier for a teenager to get a gun than alcohol in this state,” said Brittany Karzen, spokesperson for the Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office.

Na’a’s plea agreement says the guns he bought from licensed firearms dealers in Salt Lake City’s southern suburbs were later sold to other people. The criminal complaint alleges that at least 25 of those firearms ended up in the hands of Oakland construction worker Falakiko Mausia and his sons.

Mausia is in his 40s with a long rap sheet. He has been convicted in California of crimes including carrying a concealed firearm in his car and meth possession.

After Lavulavu was arrested in February 2022, he told the ATF that Mausia would pay him via Zelle and text which firearms to buy, according to the federal criminal complaint against Mausia. Prosecutors said Lavulavu told the federal agency that Mausia and his son Okustino would drive from Oakland to Utah to pick up 10 to 13 guns at a time and bring them back to California. Several were ultimately recovered by law enforcement in the Bay Area and L.A.

“Once [Na’a] purchased the firearms, I would obtain the firearms from him and would then provide the firearms to individuals who traveled to Utah from California to obtain the firearms,” said a June 2022 statement Lavulavu signed before he pleaded guilty to dealing in firearms without a license.

He was “essentially a ‘middle man’ in a firearms trafficking organization” who “facilitated the trafficking of at least 25 firearms,” the statement said.

In August 2021, Okustino Mausia sent Na’a a handgun shopping list.

The messages show Na’a, who is now 36, was aware of the regulations prohibiting straw purchases and how to get around them, according to federal prosecutors. He spread his purchases across multiple stores and tended to buy only a small number of guns at a time.

But Na’a kept pushing his luck. Beginning in September 2021, he visited the C-A-L Ranch farming and outdoor store in American Fork six times in four weeks, purchasing at least 14 handguns in total, prosecutors said. On his sixth trip, Na’a allegedly bought four Springfield handguns from the clerk working the gun counter.

One of the store’s employees then called the ATF to report the suspicious repeat purchases, which triggered the investigation that would land Na’a behind bars.

In August 2022, Na’a pleaded guilty in U.S. District Court in Utah to dealing in firearms without a license and providing false information when purchasing a gun. That November he was sentenced to 18 months in federal prison. He was released from federal custody on Dec. 4. Earlier this year, Falakiko Mausia and his two sons each pleaded guilty in Utah to federal counts of dealing firearms without a license, for which they were sentenced to periods of probation.

Reporters reached out to the five defendants and their close family members — all either declined to be interviewed or could not be reached for comment. ATF spokesperson Kristina Mastropasqua also declined to comment on the Utah case.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

However, Mastropasqua said in an email that straw purchases are “a grave threat to public safety” and “the [linchpin] of most firearms trafficking operations.” The illicit transactions “make it possible for firearms traffickers to effectively circumvent the background check and recordkeeping requirements of Federal law,” she said.

The Tongan connection

Interviews with law enforcement agents, relatives and other members of the Salt Lake City-area Tongan community paint a picture of a tightknit, religious family. But some of the family’s members have had repeated run-ins with the law.

Restaurant owner David Lavulo’s daughter married into the extended Na’a family. On a recent November day, he laid several broad taro leaves out across his hand, which he cupped to form a bowl. He piled glistening chunks of roast lamb in the depression, then poured a ladle full of coconut milk in before wrapping it all up into a green ball, which was then cooked in aluminum foil.

The octogenarian has been making lu sipi this way since before he opened the unpretentious Pacific Seas Restaurant in 1991, 22 years after he arrived in San Francisco, had a family and ultimately wound up in Salt Lake City.

Lavulo is a self-styled protector of Tongan traditions who grew up on the archipelago but has lived most of his life in the U.S. To him, Pacific Seas is a place to bring Tongan American families together.

“I want to maintain the Tongan culture and the language, but … it’s a completely different life here,” he said.

Just 24% of Utah’s population is nonwhite. Most of that diversity is in the Salt Lake City area, where the concentration of people who identify as Tongan is the highest in the U.S., followed by counties in California and Hawaii.

These islanders — or their forebears — from the small Polynesian kingdom were drawn to the Mormon promised land after missionaries converted a large portion of Tonga’s native population beginning in the late 1800s.

That well-trod path brought Lavulavu’s parents to the U.S. in the 1970s. Today, Lavulavu and his wife, Maheikau, run concrete and home healthcare businesses in the Salt Lake City area.

The Lavulavus worship at the local Mormon church and host family barbecues outside their small red-brick house. Approached outside the home one afternoon in September, Maheikau declined to comment. “What good are you going to do for us?” she asked.

Across the street, set against a jagged, snow-capped stretch of the Wasatch Range, is American Fork High School, where their daughter earned a scholarship from the National Tongan American Society and both of their sons played defensive end for the Cavemen.

Speaking generally, in these suburban communities, young Tongan American gang members live double lives, according to Salt Lake City metro gang unit Det. Jerry Valdez.

“The Polynesian kids are really good at going to church on Sundays,” he said. Then, “when they would go out and commit crimes, they’d have the bandanna in their left pocket, but the Book of Mormon in their right.”

The bandanna is always blue for the Tongan Crip Gang. More than three decades ago, members of the violent set left Los Angeles for Salt Lake, where the gang flourished, Valdez said. Police would not confirm whether Na’a or Lavulavu are gang-affiliated.

Pona Sitake, who is Lavulavu’s lawyer and his second cousin, said the path to crime for young Tongan American men is usually through gangs. Many join gangs to disassociate from their Tongan heritage and be more American, while making quick money for their families, the attorney said. Sitake declined to answer questions about Lavulavu’s gang status or his case.

Maheikau Lavulavu grew up in Southern California and attended Hawthorne High School, the same school where her nephew, Vainiaku Na’a, would play varsity quarterback and strong safety 20 years later. Na’a grew up in Inglewood, near the heart of Tongan Crip territory.

Lavulo described the Na’a family as “good people” but said he was aware Vainiaku had been in prison. Lavulo used to live in an area of Salt Lake’s west side long plagued by Tongan street crews, including the Tongan Crips, but he said he never had any problem with gangs because he raised his children well.

“Don’t blame the gangs from California because gangs are everywhere,” he said. “It starts from home. Parents need to pay attention.”

‘They sold the gun anyway’

Chad Abel has been shooting since he was 6 years old. Coming from a long line of cops, he went the military route, serving more than 20 years in countries around the globe. Now, he says, working the gun counter at the C-A-L Ranch in American Fork helps him keep his PTSD in check.

Sporting a gray beard, camouflage American flag cap and his employee vest, Abel — like workers at other stores Na’a visited — said it’s easy to spot a straw purchase: “If you’ve done this as long as I have, you know the flags to look for.”

Abel did not recall having interacted with Na’a, but said he and his co-workers do report suspicious purchases to the ATF.

Gun shop employees described various questionable scenarios. Maybe a man comes in and picks out a gun, but his girlfriend completes the paperwork to buy it. Or perhaps someone asks for a specific model but doesn’t know anything about it. Or maybe a customer appears to be receiving directions by phone or text.

In April, Rep. Jason Crow (D-Colo.) reintroduced a bill that would require firearms dealers to undergo training every two years on how to identify fraudulent or unlawful purchases and to post information about illegal firearm purchases. The legislation, which Crow has introduced each of the last three years, is stalled in committee.

“Federally licensed firearm dealers should be the first line of defense to prevent guns from falling into the wrong hands,” Crow said in an emailed statement. “But right now firearm dealers aren’t required to undergo any training on how to spot malicious actors or illegal purchases.”

It’s a problematic system that allows thousands of guns to stream to criminals each year in part because “nobody in a gun store is a behavioral expert,” said Vasquez, the former ATF program manager.

Donny Hacker, a former investigator at the ATF’s Salt Lake City office, said if Na’a had switched stores more often, he probably could have continued undetected. When Hacker inspected dealers, he said, he would advise them to file records alphabetically to make it easier to notice frequent buyers.

The ATF aims to inspect dealers every three to five years, but it often falls far short of that, agency data show. That means many problems go unnoticed and unaddressed.

“Because we had so few people, it was not unusual to go into a gun dealer who had maybe been in business for 20 or 30 years and had never been inspected,” Hacker said. “I never once in all my years of working for ATF ever saw a gun dealer who didn’t have violations.”

Many violations were the result of “really sloppy record-keeping, and the busier the dealer was, the worse it got,” he said. “Maybe they forgot to get a signature or the correct day, or somebody forgot to check a box, or maybe the guy checked the box, ‘Yes, I’m a felon.’ But they sold the gun anyway.”

One way for a dealer to get a violation is by failing to document a multiple sale. When someone buys two or more handguns within a five-day period from the same store, the dealer is required to promptly complete a form and submit it to the ATF and local law enforcement.

The dealers Na’a visited sent in several of these forms after his purchases. But it wasn’t until the ATF received a direct tip from a dealer that the agency discovered some of the guns were used in crimes shortly after Na’a bought them.

At least seven guns Na’a bought were recovered in California by law enforcement during criminal investigations within one year of their purchase, according to court records. Police found one of the guns in Emeryville, 750 miles from the Utah store where Na’a had bought it just two weeks earlier.

In September 2021 alone, Na’a made at least five separate multi-handgun purchases, according to the criminal complaint against Lavulavu. But two sources with knowledge of ATF practices said the federal agency typically only reviews multiple sales forms after an investigation is underway. The forms, one of the sources said, “are generally never looked at unless something tells them to.”

‘Ready to move on’

On Nov. 2, Siosifa Lavulavu sat quietly at the defendant’s table in a seventh-floor federal courtroom in downtown Salt Lake City.

He was there to be sentenced after pleading guilty to one count of dealing in firearms without a license. The appearance marked the end of the two-year process that brought Lavulavu, Na’a and the Mausias to justice for their respective roles in the interstate gun-running operation.

Hunched over in a white short-sleeved button-down, wrinkled gray pants and chunky white sneakers, Lavulavu hardly moved as Sitake, his lawyer, addressed the court.

“I do believe 24 months of probation would be a sufficient sentence,” Sitake told Judge Howard C. Nielson Jr., affirming the prosecution’s suggestion.

Nielson then offered Lavulavu the chance to rise and give a sentencing statement. Lavulavu mumbled a couple of contrite sentences.

“I’m just ready to move on,” he said. “I’m truly sorry to be involved in something like this, and I’ve learned, and I’m ready to accept my sentence today.”

Minutes later, Nielson sentenced Lavulavu to two years of probation and 50 hours of community service.

Lavulavu was free to go. He, his son and five women there to support him declined to comment as they exited the courtroom.

For Lavulavu and Na’a, buying guns for other people led them to this courthouse. But for every straw purchase that results in criminal charges, an untold number go unnoticed and unprosecuted.

Last year, President Biden signed into law the most consequential federal package of firearms restrictions in years. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act provides the ATF with “additional tools to combat illicit firearms trafficking and help prevent prohibited persons and criminal organizations from obtaining firearms,” agency spokesperson Ginger Colbrun said.

“ATF has been involved in investigations that have resulted in charges against more than 200 defendants under the new BSCA straw purchasing and firearms trafficking statutes,” Mastropasqua said in an email.

Prior to the law’s enactment, “straw purchases” and “firearms trafficking” were not federal crimes. Instead, prosecutors had to prove that someone lied while purchasing a firearm or dealt without a license. Since the law passed, 47 defendants have been charged with straw purchasing and 131 with firearms trafficking, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

“The BSCA is a big deal,” said Gary Restaino, U.S. attorney for Arizona. “Instead of charging … a false statement to a federally licensed firearms dealer, we can now charge the straw purchase.”

Under the new law, the ATF has made changes to a federal form that helps determine whether a dealer can legally sell someone a firearm.

Now, in addition to asking if the purchaser is “the actual transferee/buyer,” the form asks if the purchaser intends to sell the firearm “in furtherance of any felony” or to a prohibited person.

But asking buyers more questions won’t prevent straw purchases, Vasquez said: “If you’re going to lie, you’re going to lie.”

Rhet Walton manages Xtreme Pawn, a shop about 10 miles north of Provo, Utah, that sold firearms to Na’a at least nine times in two years, according to federal prosecutors. He laughed when asked whether anything can be done to stop straw purchases.

“Just people being honest. The dishonest person, nothing is going to stop them from being dishonest. They’re going to find someone who will work with them.”

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.